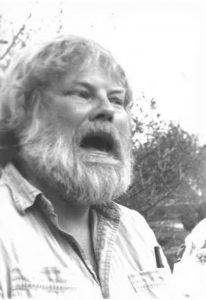

Gone ten years now, he could make the crooked and the scheming hear the protests of those they were about to trample, betray, shut out. He planted himself firm in the earth like an oversized field thistle, stubborn, always poking; a chain-smoking truth-teller who could make the corrupt and bullying close their mouths and walk away.

He evened the field. He was so large he could speak for multitudes—Whitman-like, in that way, and in others. Did he resist much? Of course. Did he obey little? Absolutely.

At 6-foot-5, he stood tall, said it all with a bold baritone voice that rolled over the prairie like a storm. Fulminating, pulling ire and fire from within his bear-sized chest and hammer-and-tonging his point with long-fingered, fury-freckled hands.

But he was more than an angry, bearded caricature. Done fist-thrusting, he’d go quiet, or turn to music: he hugged a piano as if cradling a child when he played Bach, and then handed the child off for a woman in a fluttery dress when he switched to ragtime, bopping with ferocity until his full-body-sweat soaked the piano bench seat.

Watching lovers in the Sea of Cortez, he produced love poems: his wife, in the water, then warm at his side. He found the humanity inside the concrete, Mao-era school rooms of Xi’an, saw tears in rain sliding off madrona leaves.

That was his greatest rebellion, I think: to remind the world to see love, hear beauty, to set down its vitriol and weapons and eat an egg roll with him while it was still warm.