Begin at the beginning – my god I sound like a first grade teacher –

first of the month, first in the morning, first kiss,

first death, first forced error. Sorrow is a rube’s game.

Until I was forty I didn’t know how hard the work

of dying was – even though I had already

lost grandparents and a father.

All the bodily fluids, viscous, meant to adhere,

ochre or crimson, pus or flourishing,

who you are, who you are, who you are.

The plastic and cotton batting square the hospice people

put on the tucked sheet is called a chuck,

as in, chuck up, or as in, chuck the body.

Break a window or wash it, the liminal remains.

Sometimes the answer to a question is all too revealing.

Is it possible to just send a text,

to open a cage and free painted turtles?

Wishes are dangerous sometimes –

past noon, at least –

even ones that are long gone.

In the sculptor’s studio I sat on a spinning stool

and he did, too. I didn’t show him my homework.

In my hand a rock, which I tasted

to determine its composition.

How does a tree taste? Go ahead, find out.

Whatever is worth doing is probably worth doing

again: washing undies, skillets, window panes.

A skip, a bounce, no, I throw like a girl, slight twist

at the wrong time. I believed in the kind of luck that could be found in the stars.

Nothing would stop me.

Living forever isn’t always the greatest.

My mother’s last four years, for example.

We’d climb out onto the roof to watch for tornadoes.

What went unasked still haunts.

If you threw a rock would you feel sorry later?

no, I throw like a girl,

slight twist at the wrong time,

in my hand a rock,

which I could taste to

determine its composition.

Break a window or wash it,

the liminal remains.

Open a cage

and free painted turtles.

Sorrow is a rube’s game.

How long would you ask for?

my god I sound

like a first grade teacher.

Living forever

isn’t always the greatest.

My mother’s last four years,

for example –

whatever is worth doing

is probably worth doing again:

washing undies, skillets, window panes.

Past noon, at least,

nothing would stop me.

When you were a child did someone answer your questions?

is all too revealing.

In the sculptor’s studio

I sat on a spinning stool

and he did, too. I didn’t

show him my homework.

How does a tree taste?

Go ahead, find out.

We’d climb out onto the roof

to watch for tornadoes.

What went unasked

still haunts.

What’s the difference between caring and caretaking?

how hard the work of dying was –

even though I had already lost

grandparents and a father.

All the bodily fluids,

viscous, meant to adhere.

The plastic and cotton batting square

the hospice people put on the tucked sheet

is called a chuck, as in chuck the body.

Is it possible to just send a text?

Will you wish upon a star?

Even ones that are long gone?

First of the month, first in the morning,

first kiss, first death, first forced error.

As a girl, I believed

in the kind of luck

that could be found in the stars,

or in love for example

who you are, who you are,

who you are.

Routine

Whatever is worth doing is probably worth doing again:

washing undies, skillets, window panes.

How does a tree taste? Go ahead, find out.

The plastic and cotton batting square

the hospice people put on the tucked sheet

is called a chuck, as in, chuck up,

or as in, chuck the body.

First of the month, first in the morning,

first kiss, first death, first forced error.

A complicated rush of feeling

and free painted turtles.

Past noon, at least,

we’d climb out onto the roof

to watch for tornadoes,

ochre or crimson.

As a girl, I believed

in the kind of luck

that could be found

in the stars or in love.

Trigger

is a rube’s game.

(Nothing would stop me.)

What went unasked

still haunts –

is it possible

to just send a text?

Who you are,

who you are,

who you are.

“A complicated rush of feeling” is a phrase from the writing of Jane Wilson

Over the years we have collaborated on a number of projects including writing daily lines back and forth, editing a literary magazine, and sharing poems. While geographically we are far apart, recently we have both experienced being caregivers, and the death of a parent. We saw this call as permission to work more directly on a project together.

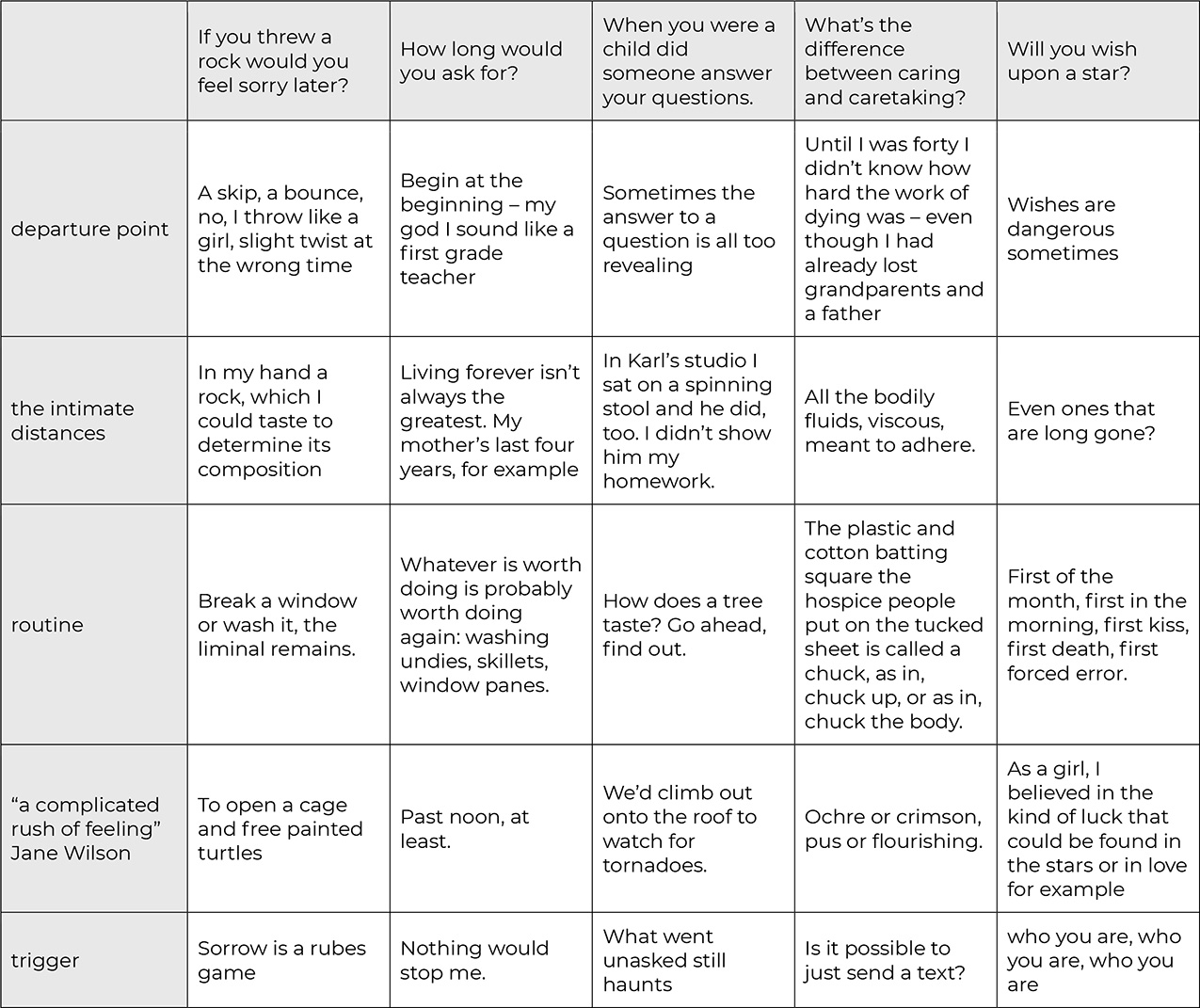

To begin our collaboration, we created what we called a “magic square” of six-by-six and chose “heart” as a theme. Then, randomly, we filled in the top row and the left-hand column with words, phrases, and questions to serve as prompts for filling in the remaining spaces. We randomly filled in the 25 remaining squares. Then we did two things: we converted the text in all the squares except those in the top row and those in the left-hand column into a poem; we made poems of the text in each row and in each column, using the text in the top row and the text in the left-hand column as titles. For both parts of the collaboration we gave ourselves rules: punctuation could change in any way; no entire square-text could be cut; small changes could be made for reasons of flow or clarity. In the end, a couple of the smaller poems were not successful, and we did not include them here.