“Please send me a stalled poem,” I suggest.

“If it’s stalled,” she replies, “it won’t be ready to send to you.”

I promise to greet it with one of my stalled essays.

Human beings are makers. It’s the only thing that gives human beings something approaching satisfaction. (Poet Frank Bidart, in an interview for Poets & Writers Magazine)

A few days later my incoming emails cradle this poem:

Early Morning When I Couldn’t Sleep

under these big shiny dreams.

Don’t Worry, Be Happy sings inside

disregarding drip-drip-drops of the dream

cloud melting

I read the lines, like them, and stuff the print-out into a file labelled “collabs” with stick-on letters that don’t match. Eventually I stop procrastinating and hunt down a stalled essay. It responds to the first half of my friend’s poem:

It wasn’t the television news footage of a furry black body wobbling on the not strong enough tree branch. It wasn’t the thought of the animal driven from the forest and into town. And it wasn’t the newscaster’s voice explaining how a dog had chased it up the tree in the first place. It was the uncomprehending look in the bear’s eyes that broke my heart.

Her poem replies:

My feet slipping on rocky

ground touched once or twice by fog. Misty

come-ons leave wet fingerprints dripping down

smaller dreams

And again, my essay chimes in:

When the largest wildfire in the state’s history was finally extinguished, the forest creatures could only return to altered habitat. Their forest was gone, destroyed by the fire itself or by the fancy backburning techniques of the firefighters, whose primary mission was saving human structures. I cannot stop thinking about the fate of that beautiful bear. Survive bear. Show us how it’s done.

Do bears dream? Desire?

My questions, unanswered

live within the rubble

of the incomplete.

Susan and I have been long-distance friends for more than ten years and began writing together as a motivational exercise. “Stalled” began with a conversation about the work left unfinished, languishing in folders.

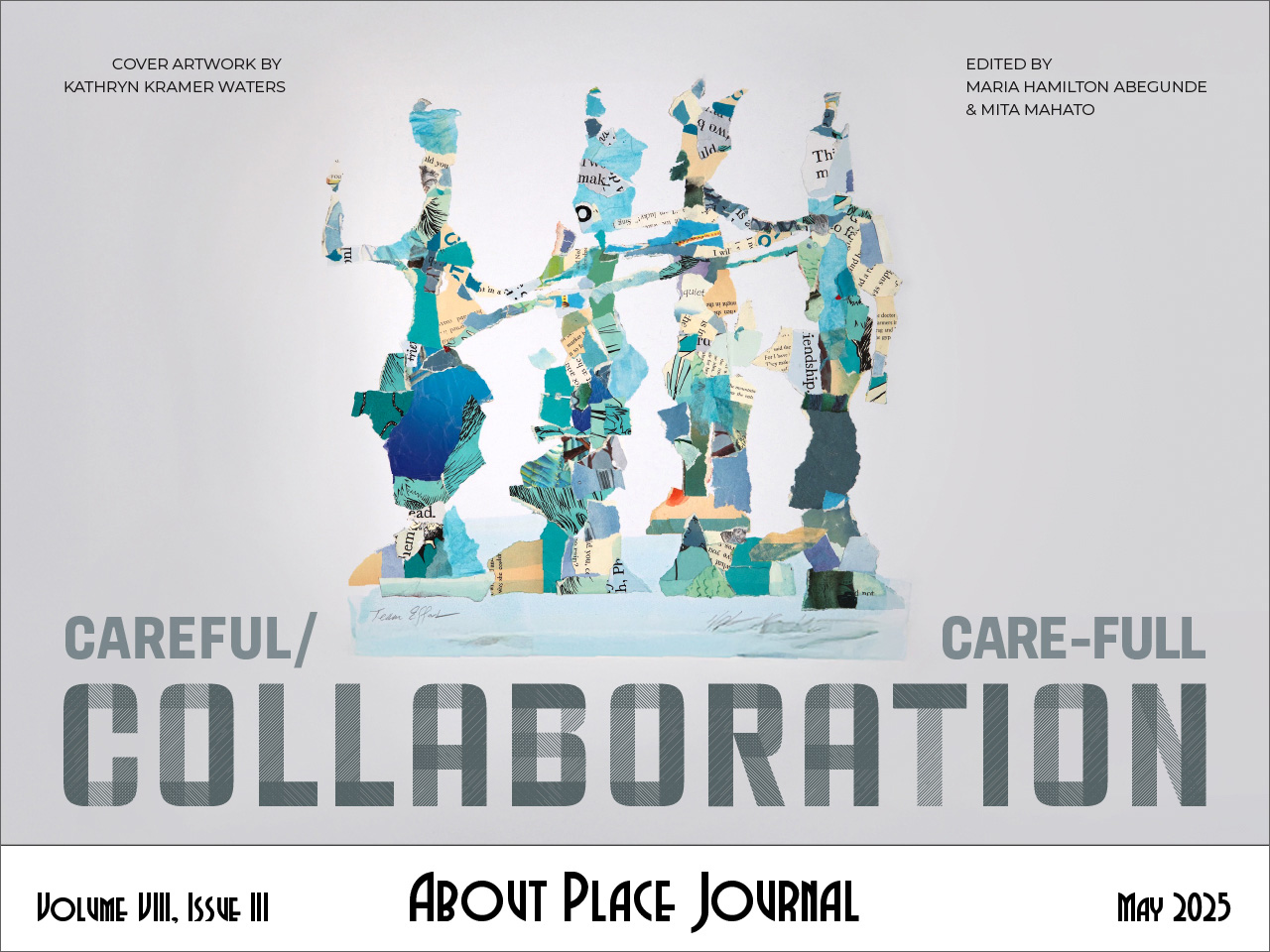

We are careful with each other’s words. We pay close attention and respond within the text. We withhold any critique of the other’s work until we’ve both passed several revisions of our own words. This allows us time to shape what we mean to say. Withholding offers a respect for process, time to allow self-directed change. Our work is two distinct voices intertwining, blending, interrupting, challenging, conversing.

Our collaborations create connection over distance through which we allow eavesdropping, hoping the reader will seek and create similar connections. Being connected—and sharing these connections—during these very difficult times strengthens us, allowing us to envision a healthier and more just future.