Bounded on the south by the old county road,

or Upper Dummerston Road, so-called,

leading from Brattleboro to Newfane;

westerly by land of Hubert Moore

and land of Walter J. Barber

and land of the Brattleboro Retreat;

northerly by and along the River Road, so-called,

leading from Brattleboro to Newfane

to a point where the fence corners;

thence westerly on land of Glen R. Grout

to a pine stump,

as the fence now runs;

thence southerly to a pine tree

with gate hung to a tree on land of said Grout

as the fence now runs;

thence southwesterly on land of said Grout

to land now owned by Mrs. F. A. Phelps,

where the fence corners as the fence now runs;

thence westerly on land of said Phelps

to a corner in the fence

as the fence now runs;

and thence southerly on land of said Phelps

to the old county highway, or Dummerston Road,

above mentioned, as the fence now runs;

and from thence to the point of beginning.

Containing by estimation fifty-two acres,

be the same more or less,

with buildings thereon.

Including the water rights connected with,

and being the same premise

this day conveyed

to me

by said Era Blodgett Tate.

(2023 reflections) I stand in the place

I remember a sand pit, like a beach

a few tufts of coarse grasses

straggling, here and there.

Grass grows up to my armpits now, so thick

it chokes my steps. The barn overflows

with hay. By the end of his life,

Claude reached beyond parsing. His farm had

paid dearly for his education. This he’d learned:

he gave the land.

Before the fence, the chickadees flitted

hemlocks along the stream,

splashing down the ledgy ravine in joyful rush

oaks thrust their taproots deep

Water seeped through soil, ants built busily

moss crept along banks.

The fence runs over what came before,

source that knits land together

mycelium stitching life to life.

This land’s health burrows with the grubs

in the soil, dwells

underground,

a web of creatures it hosts and spreads,

the fox who hunts here, neighbors’ footsteps,

all contributions bank abundance—

provenance from the dream of beginning.

This land grows a rare devotion.

Ravens nest in the pines

mushrooms slow

by the stream, a farmer drives by, speaks

to the team who haul a load of squash

from the field. The lumpy pile, shades of orange

and earth,

soft sound of hooves on the dirt road.

The College of Agriculture

1920-21 Catalogue:

Curricula in Agriculture

It is the aim of this College to impart

to its students

such theoretical

and practical training as will serve

to fit them successfully

to engage in agricultural pursuits,

using that term in the widest sense;

that is to say,

including not only the conduct

of farming operations,

but also that of teaching

or research in agriculture.

While its fundamental concept

is to make agriculture

and subjects cognate

thereunto

the main line of effort,

the course is broad in its scope

and includes mathematics, literature, language,

sciences and other cultural studies.

The technique of the sundry operations

is exemplified,

so far as time,

means and equipment permit,

but the emphasis is laid on lectures, text-books

and laboratory work

somewhat more

than upon field operations.

Haverford College,

Main Line/Haverford, Pennsylvania

Class of 1997:

English Major

For my thesis, I chose

to study a Black woman

anthropologist and author

whose work, translating rural, agricultural

Black culture

into written, published English

in the 1930s, spoke eloquently

to me,

there in academia, where my work

was praised to the skies

whilst I applied it to their

theories.

Following her example

I developed my own logic

writing about

the invisible

woman

who translated the conversation

about the sound a farmer used

to tell his mule to go.

After I studied abroad and took American

Literature classes in a university

in Santiago—

in order to study the culture

that mystified me—I was told

I’d missed my chance

to take Junior and Senior

Seminar in the preferred order.

This set of dyptychs is a collaboration between found poems from documents circumscribing the life of Claude Tate, the predecessor farmer on my family’s farm, with poems of my own experience growing there, claimed by the same land and somehow more loyal to it than to the human institutions that intersected and bound both Claude and myself. The contrasts and common threads intertwine and inform each other, leading to new questions about the power of land to affect human community and vice versa.

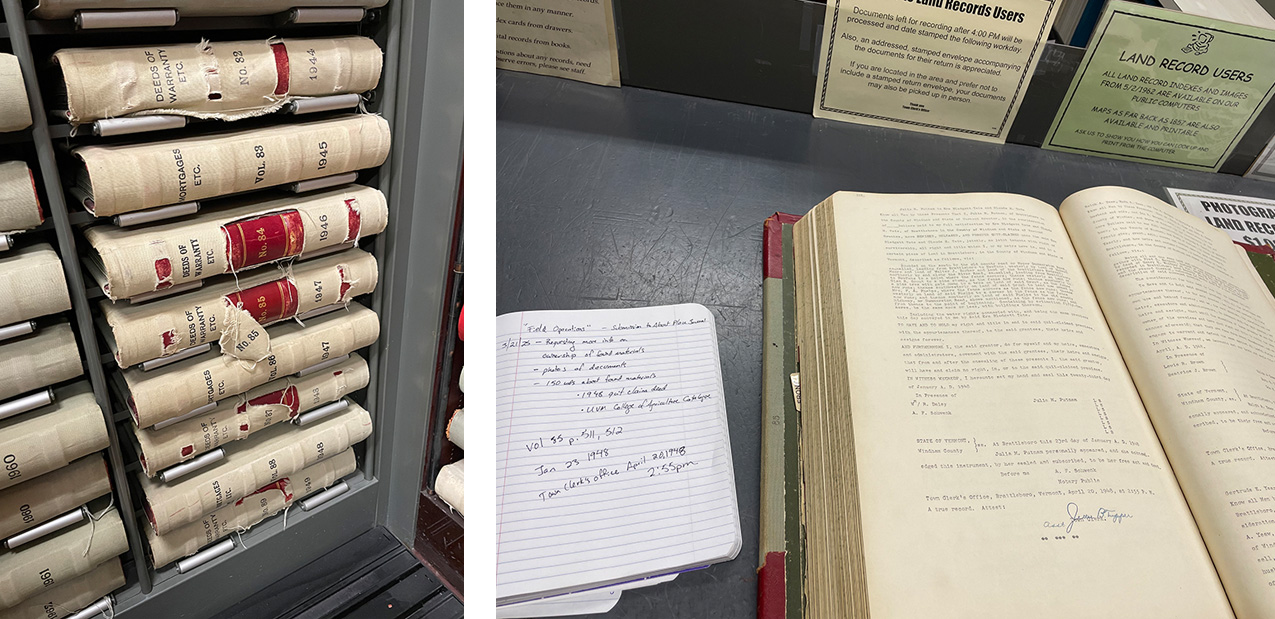

I am fascinated with the formality of these found texts, as compared to the intimacy and raw connection I experience on the land and listening to stories told by people who remember Claude. The texts are abstractions much like the institutions and repressions they embody. I enjoy setting their archaic language, which has its own beauty and rhythm, against a more flowing description of sensory experience. Reckoning with the historical ironies—that have had real, earth- and life-shaping implications both for Claude and for my family—in a literary form has been satisfying, even healing. I have been assisted in locating and accessing the found documents by real, breathing human beings, including Jeanne Walsh, Research Librarian at Brooks Memorial Library; Jane Fletcher and Alina Kulpaviciute, Assistant Town Clerks at the Brattleboro Town Clerk’s office; and Rhonda Hayward, Team Support Generalist, UVM Registrar’s Office.

Found materials used in these collaborations:

- 1948 Quit Claim deed, volume 85, page 512, Brattleboro Land Records in the Brattleboro, Vermont Town Clerk’s office (a public record) (pictured below)

- University of Vermont Catalogue, 1920-21, p. 185 (“all works published in the United States before January 1, 1930, are in the public domain”—from Circular 15A of the United States Copyright Office). Assistance in finding this document was provided by Rhonda Hayward, Team Support Generalist, UVM Registrar’s Office.