Induction Cuts

Wandering these galleries, eyes and palms seven decades shut

from war. Plane after plane: my life buoyed and parked above

me while museum goers don’t know they’re touring frozen strips

of my story. Early Years Gallery: the blue and yellow of the

only surviving B-10. Not Dayton. Corona. Queens. Twelve years

old, I gazed at those winged walruses—tucked between the East

River and Flushing Bay—flying in aluminum formation over

my walkup. Their rudders’ white and red barber pole stripes

would put my mind in mind of battles and induction cuts—

these days, my biggest battle is managing my bladder.

Next row, perched on astroturf: my open-cockpit wood

and fabric primary trainer. Not Dayton. Down South: Sage

Hall. Dixie’s shin. Moton Field. Two-seater. PT-19. Better ground

handling in humid-as-cotton-wedged-in-your-throat-August in

Alabama. Especially coasting on that in-line air-cooled engine.

My sheepskin flight jacket. Those goggles I’ve traded for thick-

lensed glasses. Presbyopia my eye doctor said. Presbyterian came

to my mind. But I grew up Episcopal. (Can squinting have an enemy?

Something I could shoot out my eyes, like I shot those Focke-

Wulfs out the sky?) Down past three generals’ outfits cocooned

in glass, I spot my basic trainer, sneak Jergens on my neck’s

skin tags and chapped hands, give that Vultee Valiant BT-

13 a once-over: that thump and rattle, that greenhouse canopy.

Down the hall, I stop. For a sec. (These days my heart—like

a Penn Station baggage handler—works harder when I walk.)

The World War II Hall? Dayton wasn’t Dayton because,

as if this gallery were a sky my plane had been shot out of,

my P-51, my Miss Jackson, had been temporarily removed

from the museum. No bubble canopy, no drop tank. So my

jaw sauntered as a little green-afroed girl, sneaking a Sour

Patch, pointed to a nearby display: wondered what it would

be like to fly one. You know, when I was your age, I

thought the same thing. I thought the exact. same. thing.

Jacqueline Johnson’s Notes:

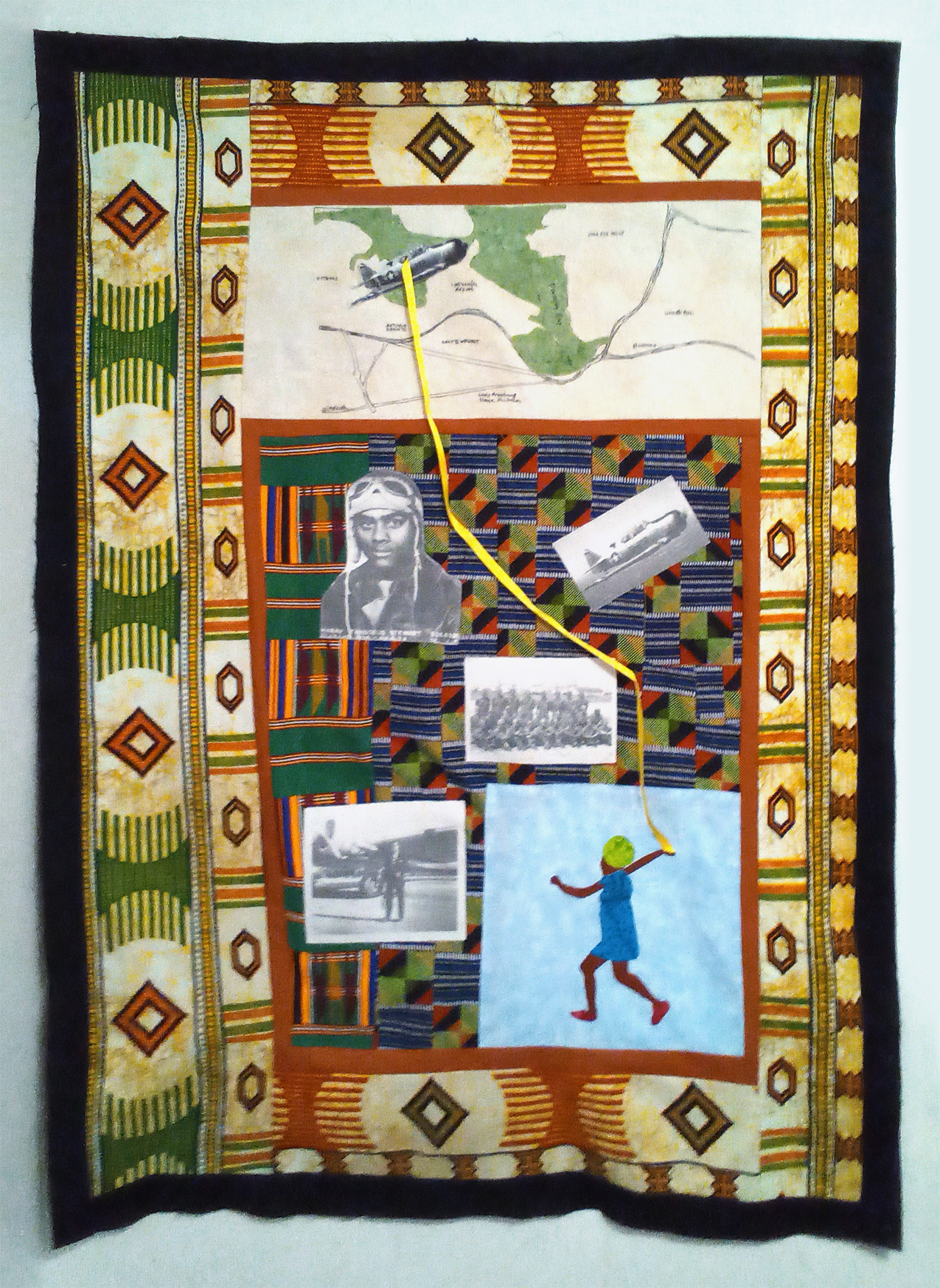

David Mills and I decided to collaborate in late January and solidified it in early February. We started out with David sending me several poems of historical and artistic figures. Initially this did not work for me. When I received the second batch of poems something in them piqued my interest. While I knew of the famed Tuskegee Airmen I had never heard of Harry Stewart. I initially did a bit of research and found both Stewart’s history and legacy intriguing and impressive. Once I saw the photographs of Stewart I was completely in on the collaboration. Who was the handsome young man who sat in the front row of photo of a Tuskegee Airmen? Of the three poems David sent to me I decided to visually interpret and to illustrate the poem “Induction Cuts.”

It mattered to me that Stewart came from Queens where I went to grade school. I had never heard of Flushing Bay and wondered where it was located? I found many images but was interested in the map that showed its proximity to the LaGuardia Airport and neighborhoods such East Elmhurst and Astoria. I drew the map of Flushing Bay by hand. As a quilter color is everything. I found a muted chartreuse, batik fabric for the water. That green became the through line in all of the fabrics that were selected. Within the quilt one will find a strip of Kente cloth of the Akan and two other fabrics that mimic Akan weavings and Adinkra symbols. This story quilt “A Ribbon In the Sky” is about Harry Stewart Jr. and the connection between generations.

David Mill’s Notes:

I did a poetry workshop in western Queens (NYC), which no longer has a significant African American population. I spotted a proper photo of a brother in the main entrance of the school and asked who it was? Somebody said, “that’s Mr. Stewart who the school is named after.” And I thought to myself, “wow, they named a school after a brother in a neighborhood that didn’t look to have too many black people.” I knew because I lived in western Queens. I did the Google thing and it turned out it was named after the father of the Tuskegee Airman Harry Stewart Jr. that my poem is about. Stewart’s father was very civic minded and had moved his wife and the then-child Harry Stewart Jr. (eventually Tuskegee Airman). They might have been one of a handful of Negro families in their Queens neighborhood.

Initially in my research, I was confused because no one in the school mentioned that the Stewart the school was named after was the FATHER of a Tuskegee Airman. But Harry Stewart Jr. (the son) was all that came up online. I figured the Sr. Jr. thing. But more importantly figured out Harry Stewart Jr. had grown up in Queens and went on to have a decorated career as a Tuskegee Airman and I decided to start writing poetry about him and a handful of poems turned into a two-year project and a book’s worth of poems.

Of Harry Stewart Jr., David adds: “sadly about two months ago Stewart died. Ironically, yesterday March 30th, I was at Yale for the 55th anniversary of what we called “the House” African American Cultural Center. And who was one of the honored? The ONLY surviving Tuskegee Airman who unbeknownst to me had also gone to Yale and of course knew Harry.”