adapted from material in Traces: Sand and Snow in Symbiosis

This is the story of how two scientists, separated by an ocean of water and a chasm of culture, came to collaborate on the creation of an earth-centered anthology of poetry that evoked their love of distant, but not-so-different, homelands. We can’t assert that our tale provides “how-to” lessons for others. However, we can affirm that the making of art and science is a communal endeavor that can—and perhaps must—be a shared creation of entangled minds and hearts.

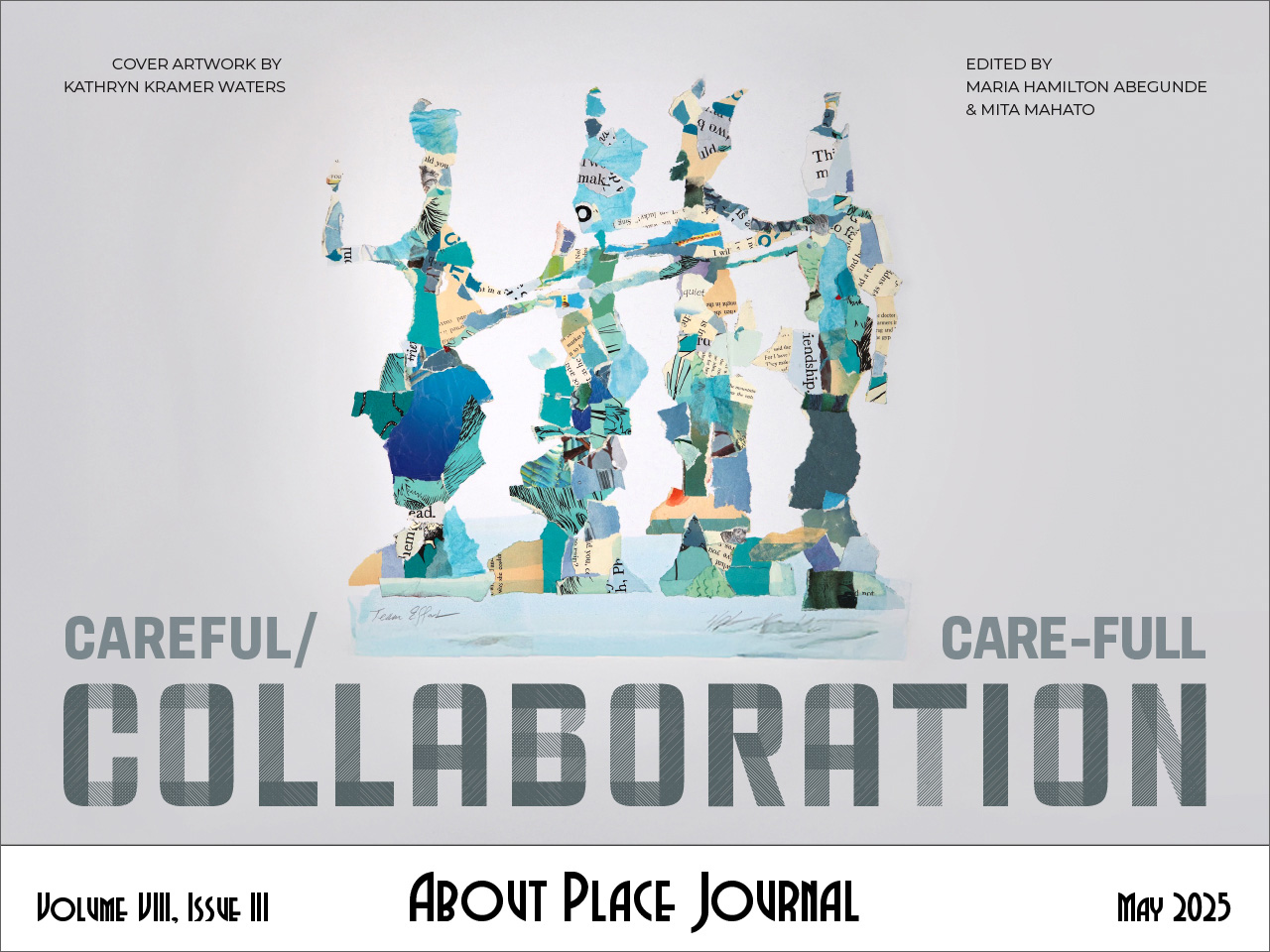

Our book, Traces: Sand and Snow in Symbiosis (Middle Creek, 2024) contains 54 ekphrastic poems from 22 Anglophone (American and British) and 16 Arabophone (Mauritanian) poets. The poems were catalyzed by photographs of tracks made by creatures and natural forces (e.g., wind and rain) leaving traces on the sands of the Sahara and the snows of the Rocky Mountains. As one might guess from the subtitle of the book, the editors are two biologists, or entomologists, or to be precise, acridologists—people who study the Acrididae (grasshoppers and locusts). As a Mauritanian and an American, we are conjoined by the six-legged creatures of our homelands and the two-legged beings of our scientific and agricultural communities.

Although we were first drawn together by the pesky insects, we grew to share a heartfelt concern for our fellow humans—for those who have come to the tragically mistaken belief that there is more that separates us than unites us. As such, we sought, along with our growing community of poets, to cultivate symbioses to join people in ways that respect cultural differences and celebrate human commonalities.

However, the book is the end of our story—or at least this chapter of our lives—and how this care-full collaboration emerged has perhaps as much meaning as does the book that instantiates our friendship. And so, we offer one of the strangest backstories of artistic creation in the history of poetry—the tale of how two acridologists (how many poets can say they knew this term before reading this essay?) came to entice some of today’s finest poets to contribute to an anthology of writings grounded in the ephemeral traces of nature.

# # #

Jeff’s perspective

A friend may well be reckoned the masterpiece of nature.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ould Babah and I met in 1997 in Cairns, Australia, at the 7th International Congress of Orthopterology (the study of Orthoptera, the order of insects that includes grasshoppers, locusts, crickets, katydids, and their relatives). We encountered one another in the course of sharing a cramped, bench seat in a minibus carrying scientists on a tour of the country’s locust control program. I found my new companion to be affable, intelligent, and gentlemanly—a person worthy of emulation. I fondly recall Ould Babah’s deep, whispery-scratchy voice, his strong-gentle touch, and his genuinely warm smile. There soon developed a nascent friendship far beyond the overlap of professional interests. How such visceral connections happen is impossible to say, but here was a man who seemed so superficially different (dark in complexion, multilingual in speech, and elegant in manners) and who felt so deeply similar (caring about family, laughing easily, and seeking companionship).

Our paths (or might I say, “tracks”) crossed again four years later at the next International Congress held in Montpellier, France. Ould Babah was studying for his PhD at the Sorbonne Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes—and dearly missing his family. So, he ‘adopted’ my son, who was 10 years old at the time. Ould Babah played warmly with this towheaded kid who couldn’t have looked more different than his own child. But my son had a child’s intuition, an affinity for adults who are kind and genuine. I could tell that Ould Babah was a devoted father, a man who loved children but had high expectations. I saw his polite, intellectual toughness with professional peers at the meeting, and I readily imagined his firm tenderness at home.

Two months later, the devastating attack of September 11th struck the United States. The first email that I received the following morning was from Ould Babah who expressed his profound sadness for the loss of life and wrote, “This is not Islam.” I kept that message for years but it was somehow lost during one of my moves between computers, so all I have is a memory—a neurological trace. Scientists tell us that memory forms by the reactivation of a specific group of neurons, a set of connections that grows stronger with repeated recollections, and I don’t intend to ever lose those connections to Ould Babah’s message in my brain and my heart. I thanked him sincerely for his compassionate message, and so began a conversation that has gone on for nearly 25 years through an exchange of emails every few months—never too long to lose track of one another.

In 2008, I was honored to be invited to serve on Ould Babah’s doctoral committee which convened in Paris for the final examination. The night before the big event, I was reading a book at a café when he happened to be passing by. Ould Babah came in with a huge smile and an ursine hug. We exchanged family news, and he asked what I was reading. I told him it was Two Years Before the Mast, a classic of English literature. He sighed and said that he wished to have time in the evening for such reading, but given his status in the community, he was invariably interrupted by people coming by his home unannounced (but not unwelcomed). According to social custom in Mauritania, he and his wife were obligated to provide a meal for even very distantly related folks. He envied my autonomy; I envied his intimate network of relationships.

Our next chance to see one another came at the International Congress of Orthopterology in Agadir, Morocco, in 2019. I had missed a few of the intervening meetings, having metamorphosed from being a professor of entomology to being a professor of natural sciences and humanities with an appointment split between the departments of philosophy and creative writing. For some years, I’d been using my scientific experiences as the raw material for researching and teaching environmental ethics and the philosophy of ecology, along with essays and books about the strange and wondrous relationships between humans and insects. It was in this context that I’d asked the governing board of the Orthopterists Society if they might consider a performance of Locust: The Opera as the opening event. I had written the libretto for this chamber opera, and I imagined that it might make a compelling bridge between the worlds of art and science. Ould Babah was the executive director (a role I’d had from 1995-2003), and he worked with a generous colleague in Japan to underwrite the performance.

# # #

Ould Babah’s perspective

Two eyes see better than one.

—Mauritanian proverb

For me, Jeff is an exceptional man in terms of both his humanity and culture. First of all, I admire his morals, along with his politeness, openness to other cultures and different religious beliefs, exemplary availability, and altruism. I also value his immense skills and broad knowledge. One aspect of his life that has greatly impressed me is his migration from being an excellent acridologist—and an exemplary biologist—to being a scholar in the humanities, where he so smoothly became an excellent writer of books, novels and other works, including an opera on locusts! Having known him has made me really want to go to the United States to discover this country whose inhabitants can have such extraordinary characteristics different from what we see in certain scenes of Hollywood films.

However, I avoided going to the United States (in large part due to difficult reasons that will become evident shortly). Nevertheless, I’ve had the chance to visit more than 70 countries including many by hitchhiking when I was a student in Iraq during 1978-1984. It was great to travel this way and above all it was highly educational, even life changing. As an Arabic proverb says: “Travel and you educate yourself.” Being a lone traveler was the best way for me to meet and to get to know young people from other cultures as quickly as possible. Being a nomad coming from a country of nomads certainly has had a great deal to do in helping and training me to better communicate and interact with other cultures and religions.

Such fruitful intercultural interactions and exchanges were particularly possible with Jeff, because he himself was intrinsically and naturally predisposed to open-minded discussion. Privately and publicly, he always sought and fought for intercultural and interreligious dialogues focusing much more on what could best bring people together than what keeps them apart. After September 11th, he gave lectures to convince the American people not to generalize about practitioners of Islam and warned against cutting bridges with these cultures and countries.

He once sent me the text of a lecture in which he mentioned my name as an example of a peaceful Muslim. Although he spoke positively about me, it must be said that when I read his words and I saw my name there, I had goosebumps of fear, because of the Islamophobia which was starting to grow in the United States. I thought naively and certainly wrongly that the FBI or the CIA were just going to read my name with the qualifier “Muslim” and come to my home in Mauritania and take me to Guantanamo. Indeed, this is what they did, by mistake, to my compatriot Ould Slahi who remained in prison for 20 years before being declared innocent by an American court. This legal ruling pleased Mauritanians and completely changed our perspective by showing the greatness of the United States through the independence and power of its justice system which does honor to this nation. During his imprisonment, Ould Slahi wrote his story in a book titled Guantánamo Diary which was the basis for a recent documentary film, The Mauritanian.

Returning more directly to the subject of our book, after my studies in Iraq and my return to Mauritania in 1985, my work involved extensive surveying for locusts in the desert. I used to sleep on or between the dunes under the moon, and it was there that I discovered the beauty of the traces left by nocturnal creatures on the sand. These were fabulous paintings which had only a very short life span. Within a few hours, the morning winds erased them forever. I told myself that it was not acceptable that these great artistic works by our fellow creatures were swept away. And that’s when I began taking pictures of them. Subsequently, I thought these images were too beautiful to stay mine alone. So, I thought of publishing them.

I soon realized that it would be good to couple these images with the traces of creatures from another land to build an artistic bridge between people through nature. I broached this idea with Jeff who was as usual very open and imaginative. He immediately embraced the concept and enriched it by offering to combine the images with poems which was simply a great idea, especially with my country being known as “The land of a million poets.”

# # #

Our shared perspective

Every animal leaves traces of what it was;

man alone leaves traces of what he created.

―Jacob Bronowski

At the gathering of scientists in Agadir, Ould Babah broached the possibility of collaborating on a project involving literary reflections on animal tracks. He’d accumulated a compelling collection of images taken from desert sands, and while Jeff is not much of a photographer, he is an avid cross-country skier and often came across animal tracks in the snow. So, we thought: What if an African and an American could pull together enough images and poets to form literary connections between two profoundly different places—the Sahara Desert of Mauritania and the Snowy Mountains of Wyoming?

Mutual trust and respect cannot be seen, but like tracks these qualities suggest a kind of hopeful movement. In a fleeting glance or an ephemeral touch, there is evidence that something has passed over the landscape of relationality. As Wallace Steven said, “The poet is the priest of the invisible.” So, it became our hope that poets, with the lettered tracks they leave on a page, might see in ways that draw distant readers into a common understanding—or at least a momentary glimpse of humanity’s common ground.

Through this shared venture and the reflections that were evoked, it became increasingly clear that we are more than a pair of scientists whose paths have happened to cross for decades. We are both men of faith: a Sufi and a Unitarian Universalist. And in this context, we have exchanged many questions of life, expressions of respect, recordings of music, and reflections on our not-as-different-as-one-might-expect religions. The overlap of our abiding values unfolded vividly when we exchanged stories of our grandfathers. Ould Babah wrote:

For example my grandfather EBBE, because of his high knowledge in religion and his well-known honesty and equity was appointed by the French colonialists as a judge among the local population in the beginning of the last century… He accepted but refused to receive any salary, despite his poverty and the difficulties of that time…

One day two persons came and started exposing their cases one by one, and during that time one of them touched his clothing… He stopped the court (a very simple court under a tree) and he said how did you touch me and what for? The person who did so said that it was just to take off his clothing a louse. My grandfather said the court is over… go to someone else to judge you. The reason behind this is because he was afraid to develop any kind of sympathy in the direction of that person which he thought may influence his judgement and make him feel that he was corrupted by that gesture!

He is since that day well known in the history in Mauritania as the “Judge of the Lice.” Unfortunately I am not sure we have a lot of judges like this in the current days.

And Jeff replied:

According to family legend, he was commissioned to make a pan balance that was to be used for weighing gold at Fort Knox (the scale was to accommodate several hundred pounds of gold bullion). Each pan was a meter in diameter. When he was finished, my grandfather placed a piece of paper in each pan and tared the balance. Then he drew an X in pencil on one of the sheets of paper. Upon putting the papers back on the two pans, the balance tilted ever so slightly but noticeably toward the paper with an X indicating that this miniscule difference was sensed by the scale! Such care and precision in craftsmanship is not widely practiced in today’s world.

I formed a wonderful image of our grandfathers coming together, with your grandfather plucking a tiny louse from his clothing and placing it on my grandfather’s enormous scale as the two men marveled at your grandfather’s moral integrity and my grandfather’s fine workmanship. Now that would make a lovely painting, if only I had talent in that realm.

In addition to being believers, we are both lovers—of our families (Ould Babah has five children; Jeff has two), of the outdoors (Ould Baba hunts for animal tracks, Jeff fishes for trout), and of poetry. Ould Babah is proud that Mauritania is called “The Land of a Million Poets,” and Jeff is chagrined that the University of Wyoming cut funding for creative writing so that we are the land of perhaps a half-dozen poets.

We are also lovers of our homelands, harsh places where the human mastery of nature is an ever-present absurdity. Ould Babah lives where it exceeds 100°F for 6 months, and Jeff lives where the average high in winter hovers at 32°F. The high and low records in Nouakchott are 115 and 41°F; the records in Laramie are 94 and -38°F. Ould Babah lives where there is 2 inches of annual precipitation; Jeff lives where there is 12 inches. Our hometowns average wind speeds of 10-12 mph (Chicago, the famed “Windy City” of the United States averages 10.3 mph). We are humbled by the places we live.

# # #

Tracing Lives

A poet must leave traces of his passage, not proof.

―René Char

The tracks of living beings are found in every environment on earth, from contrails produced by airplanes filled with travelers, to bubble trails made by humpback whales, to slime trails left by snails, to root channels formed by trees. Creatures with 0 to 300 legs (most often 6, sometimes 4, and occasionally 2) leave behind evidence of their passing across mudflats, lakeshores, sand dunes, and snow drifts. Each set of tracks is a story, whether a short tale or a chapter in a grand narrative. Coming upon a series of foot, paw, hoof, or tarsus prints evokes a sense of mystery. One is drawn into imagining what fellow being came before us, when its path crossed ours, where it was going, and why it was moving. Was it a camel carrying goods to a nomad encampment, a ground beetle seeking shade in the heat of the day, a weasel hunting for its dinner, or a child learning to ski?

Few marks in nature more powerfully stir the imagination of hiker than a clawed, paw print larger than a person’s hand. In this way, tracking and storytelling converge in a profoundly human manner. As philosopher Richard Kearney contends, “Telling stories is as basic to human beings as eating. More so, in fact, for while food makes us live, stories are what make our lives worth living.” And in the course of our species’ history, both eating and not being eaten often came down to our ability to read tracks—the stories of prey and predators.

Under extraordinarily rare conditions, tracks may last for millennia. We have fossilized evidence of dinosaurs stomping across wet soils a hundred million years ago. But the staggering majority of footprints disappear within days or hours. Likewise, our technological trails rapidly dissolve into vestiges of human cleverness. The probability of any printed material lasting as long as the Diamond Sutra—the oldest book at 1,157 years, which is about the longest life expectancy of the most stable digital media—is virtually zero. Ironically, this ancient Buddhist sutra addressed the illusory nature of the material world.

We have to accept that our tracks—whether concrete highways, optical discs, or bound books—are evanescent evidence of our fleeting presence on this planet. The collection of photographs and poems that we assembled is less like the ancient Roman roads across Italy or prehistoric aboriginal songlines across Australia than it is akin to snowshoe tracks in a blizzard or camel tracks in a sandstorm. But maybe, just maybe, some of these poems will sink into a reader’s heart and mind. From there, a stanza might become part of that person’s story, and their children’s story, and so on—echoing across generations and never quite fading into forgotten silence. After all, the wonder of tracks is their capacity to catalyze the imagination. But in the short-term—a time period of less fantastical possibilities—we imagine that our ink-on-paper creation might connect our fellow humans in space, whatever its temporal fate. Perhaps it could even become a cultural symbiosis.

In biological terms, symbiosis refers to any relationship between organisms, including mutualism, commensalism, parasitism, and predation. However, for well over a century, the colloquial meaning has been a relationship of joint benefit (what scientists refer to as “mutualism”). Perhaps the scientist’s nuanced understanding reflects many of the interactions between nations in the modern world in which the net benefits are distinctly unidirectional and the interaction can be outright predatory. But the goal of our poetic project was to foster reciprocity—a cultural mutualism of intellectual understanding, aesthetic respect, and creative inspiration. The social evolution of interdependence, rather than domination, might be catalyzed in some small way through the arts as a means of expressing the ecological connections on which the global network of lives—both human and other—finally depends.

# # #

Ultimately, what drove this project was our shared desire to take some action, however minute, to “be the change you want to see in the world,” as Mahatma Gandhi admonished. We are too old to be naïve but perhaps too wise to be despondent. We are two chronologically advanced and geographically distant friends, having formed a virtual community of poets who embraced a vision of using the images of tracks made in sand and snow as the means of uniting distant lands and people. As Nelson Mandela advised, “The moment to bridge the chasms that divide us has come. The time to build is upon us.”

What we share as humans is so much deeper and more powerful than the differences arising from accidents of time and space: when and where we happen to have been born and live. This is not to minimize cultural diversity, as such differences are sources of energy, novelty, and wonder. We speak different languages, learn different prayers, listen to different music, read different poets, and eat different foods. But these are varied means to the shared ends of joy, reflection, intimacy, compassion, pleasure, and meaning.

In the end, we are merely two men living 5,500 miles apart and believing that the world needn’t be a place of hurt or hate. Traces is our small contribution to creating a better world, a tiny step toward tolerance. Having lived through a period of human history with more than a hundred wars, twenty-four famines, twelve genocides, and a global pandemic, our defiant faith crystalized in a collection of poems—a spiritual footprint that has not faded into despair. Perhaps optimism is unjustified at this time in the world, but this book is our vestige of hope.

Will this exchange of images and words change hearts and minds? Who knows? According to a Mauritanian proverb, “He who begins a conversation, does not foresee the end.” The work to overcome bigotry and distrust may well be a Sisyphean task, but the Unitarian Universalist minister, Reverend Wayne B Arnason, tells us:

The way is often hard, the path is never clear,

and the stakes are very high.

Take courage.

For deep down, there is another truth:

you are not alone.