Umwelten

Winter Crane Fly

If I were a winter crane fly, my blood would have antifreezing chemical properties. Should light flicker across the eyes at the top of my head, suggesting the air is sunny and just above freezing, something would come alive in me. If I were female, I would slip among the swarms of males to mate. After a long time living as a grub, this frenzy would be one of the defining moments of my life. I would not live long as this flying version of myself. This sun on the snow, the crisp of the air, none of it would fit inside everything I grew old as a larva knowing of rotting logs and dead leaves, root burrows and mouthfuls of soil. I would not be human, so I would not philosophize the experience. So many cells and ganglia would be humming my new flying body. Somewhere in this cold woods a maple tree has been wounded and sap runs down its side. I would like to lick it, but like angels have no genitals, in their final instar winter crane flies have no mouths. And yet I am drawn, data proves it, to these places where the world is sweet.

Katydid

Night sparks along the threads of my antennae, tingling into the nerve bundles behind my eyes where, like a human, I keep my sense of knowing. I keep fear in my belly, which is bright red. If you startle me, I will fling wide my wings in a spasm to reveal this belly, the sight of which is designed to make you feel as if you are the one bleeding. I like this clever power about myself. I love the leaves on an orange tree better than is good for me or you or fruit or land. I love to hear a male rub his smooth wing over his richly carved wing. He is born carrying this shield etched with every battle he ever dreamed. I hear him throbbing across the grass in my foreleg where the tympanic organ, that hide drum of my own taut hind leg, beats his song back through me. In the same way I hear the water rippling on the pond and the wind shushing through the bluestem. Petalfall has begun and soon I won’t fit inside this shell of a body.

Pine Processionary Caterpillar

If I were a pine processionary caterpillar, I would not like it. Though I would not have these notions of “I” or “liking.” I would just follow the silk coming out of the caterpillar in front of me as the caterpillar behind me followed the silk coming out of me. Or maybe I would like the way it feels to be myself and also a train of three hundred or more, a cursive being in search of some other tree whose roots will feel like home but also different, because we are feeling like ourselves but also different.

If I were a pine processionary caterpillar, I would wrap that silken trail around and around myself as I burrowed into the soil. I would melt in there entirely down to goo. I would have to lose everything I ever was in order to become a creature with wings and a frantic urge to fly and fuck and lay spike-covered eggs among the pines as fast as possible. Sensing perhaps that this was the only day of my winged life and it is slipping away.

The Limits of Human Feeling

Umwelt is a concept developed by the biologist Jakob Von Uexküll, who was trying to explain perception and why it is that perceiving feels like reaching from a place of deep loneliness to touch someone. Umwelt holds all the meaningful aspects of the world for a particular creature. The mind and the world are inseparable inside the circle of umwelt because the mind interprets the world.

When two umwelten interact, this creates a semiosphere. In a semiosphere the world does not exist objectively to be sensed and experienced, but is a structure where thinking and the things you think about operate together to produce sense and experience.

Sometimes I will look at a critter very closely for a long time, wondering how it feels to be them. This experience of noticing an umwelt other than one’s own is called umbegung.

It is a common sensation among humans to feel as if it is possible to know someone else, anyone else, as you know yourself. It is one of the great pleasures of our beings to feel as if that sphere around me is growing to include you, and anyone you ever understood. We’ve been known to take it to the point of delusion. It’s hard to stop, it feels so good, this Who are you? emerging in our minds beyond the place of questions and problem, break-ups and funerals. It’s hard to contain the magic of realizing that there is a you, you are not me, and here we are, beside each other.

The Twitch

The green striped mapleworm becomes the rosy maple moth, which is sometimes pink and yellow striped, like a candy or a pair of mittens on a child. Their lives are divided into something called an instar, of which they have five. In one, their heads are black. In the next they are yellow. Later they will be red. Between one instar and the next they grow horns and spikes along the sides of their back. In their last instar they burrow into the chambers between the roots of the maple tree.

When I touched the cocoon, I expected something silken. But a cocoon is just another form an exoskeleton can take. The moth is not in there, she is there. And when I caress her ballet slipper of a body, the cocoon rustles away from my finger, while I too pull back, startled to have met this being, alert, awake, alive to everything beyond herself.

Nowhere Else

Driving the long stretch through lava fields, large blankets of pink and magenta flowers stretching up the mountainside caught my eye. As I pulled the car over, my kid in the backseat groaned, my husband groaned, my mother-in-law said, “Oh you two, leave her alone.”

Stopping in a ditch beside the highway, I compare the flower to pictures in my field guide. A kind of knotweed. Up close I could see they grow from the crevices between rocks shining silver with lichen. Every stone was so jagged it was hard to walk—the wind and the rain and the lichens and weeds had hardly begun the work they would do to soften this place to soil again.

I was preoccupied on that drive with ideas about the everyday workings of colonialism and how the left hand doesn’t always know what the right is doing. And all that the ease of such ignorance, or the pretense to such ignorance, enables. On the left side of the highway was a military base. While my family played I Spy, I counted how many armored trucks passed us.

On our right were the Mauna Kea observatories, where scientists trained in western epistemologies will tell you they are engaged in a beautiful endeavor trying to see the past and the future through spots of distant light. The native Hawaiian protestors who blocked the access road to these telescopes explained and insisted this mountain is a sacred place, home to the gods who sustain them. And that development of another telescope, like the ones before, would pollute and destabilize the fragile aquifers that nourish this land.

The sky was so clear we could see snow gleaming at the top of the mountain. And through that snow, the off-white domes of the six observatories already in place. Traditionally, land in Hawaii was parceled out, not in the rectangles typical of European allotments, but in triangles that trace up the side of the mountain and down to the sea. Because fresh water collects at higher elevations and trickles down, the triangle ensures people have to think about the wellbeing of the entire watershed. There is no upriver to fight over and no downriver to disregard. The very highest elevations were the homes of the gods—you needed permission and a very good reason to go there. To take so much as a tree from that precarious and ethereal place required a major sacrifice.

Funding for astrophysics often comes from the Department of Defense, planning for the next war, or from private industry, allocating their venture capital according to predictions about future profits in sectors like satellite surveillance. A public university funded my trip here too, so I could write poems about how I feel about lava crickets. My left hand thinks it is hacking the system for the sake of art and conservation, while my right knows it is convenient to send the intelligentsia on colonialist field trips to write ineffectual and inward-looking poetries.

Pink knotweed is known as one of the prostrate herbs. A naturalized non-native species, it kneels at the foot of Mauna Kea. The alpine summit is Wao Akua, the realm of the gods. It is a sacred place. I did not go there, as I had no need, no invitation, no gift or sacrifice. I stood with the lovely knotweeds, among the remains of the protestors’ tent city, looking up at the mountain, then down to read the educational plaques they left behind.

The summit was formed in an ice age when the lava was frozen. Even now the aeolian ecosystem freezes nightly, the ground is a layer of ashy permafrost, there is intense ultraviolet radiation at such heights. It is home to agrotis moths, cutworm caterpillars, lycosa wolf spiders, springtails, the wēkiu bug. On an island overwhelmed by invasive species witnessing one extinction after another, these acres are a last refuge.

The palila, a lovely yellow-headed member of the honeycreeper bird family, now lives on this summit and this summit alone, eating the maimane drifting down from passing clouds and fluttering among the hardiest shrubs of ‘ohi’a lehua, which put forth incandescent blooms of pink, each one opening like a radiant sun in the distance.

‘Uhini Nēnē Pele

I have been going to sites of aftermath to see who can live and how among the ruins. I do this, I tell the people who provide the grants, so I can learn something useful about how to live and love and survive and save from within the sites of our own destructions. I do not mention how much I myself feel like an aftermath.

I went to the slopes of Kilauea looking for lava crickets only found on the barren fields of a recent lava flow. They are extraordinary beings, appearing it seems from nowhere after the end of the world to live on proteins in the spume of the waves that rise up from the sea. They make no sound, which is why my friend the animal behaviorist keeps going back to study them. She wants to understand how they find each other.

The Hawaiian people have of course known these creatures for as long as they have known the lava and call them ‘uhini nēnē pele.

In the stories my people tell, crickets are the old ones who stay up all night recounting the whole history of the world. The chirping of crickets, our mystics say, is the first sound you hear after you leave your body.

Brian, who used to collect water samples and count macroinvertebrates for our coalmine-ravaged watershed, came with me to help look. He’s the kind of person who will lift every rock in a field before he gives up, while I quickly grow distracted by the spackling of lichens that return with the crickets when the ground is cooling. I wander to the ‘ohi’a lehua tree at the edge of the field, which is the next to come back, their pink inflorescences blooming so bright against the black earth, their roots burrowing through the thin dust between the stones to make them soil once more. Beneath my feet the hardened ground still seems to swirl. I follow a scorched white tree from its toppled crown to the deep hole where the lava pooled a long time among its roots. In the depths, small but very green ferns grow.

The heat of the sun was becoming too much, so I convinced Brian to try the method my friend had used the first time she stumbled on lava crickets, by accident while researching another insect. Like her, we grabbed an empty wine bottle from the trunk and baited it with cheese from our cooler of snacks and left it sideways among the rocks. These days she prefers to use plastic bottles and bread, though she doesn’t want me to give more details than that, as she worries about tourists harassing the crickets.

Then we left to walk a spiraling path through another field where native Hawaiians had carved concentric circles into the rock and buried their newborns’ umbilical cords. The generations of markings looked like a map of the stars. Acknowledgements of guilt are so useless, and yet I feel I should say it was my government that stole this land and my people who became and become and keep becoming a people who only seem to know how to look for the ends of the earth.

On the other side of the mountain a new lava lake boiled and oozed. Night fell. Brian and I had sex in the rental car like teenagers. I wished so much then that there was a way I could be at the beginning of something again.

The bottle was empty as we expected it would be and I was glad not to have caught a cricket. Even though we would have put it back on the ground after holding it a moment, I realized I had not really come here to see them, who I’d already seen in Tupperware in my friend’s lab. I’d come to see everything else that made them and everything else they had made. Above us, the moon was as full as I’d ever seen, the air smelled of smoke and a coming rain.

Back home, my friend taught me how to find katydids in the field near our offices. I don’t belong here either, but I think if I keep trying to learn and unlearn and give more than take, maybe someday I could. Before we began our path around the perimeter of a small pond she pointed to the low grasses and clover and said that humming is the crickets. She pointed to the higher branches of trees—there you’ll hear the cicadas. Then she gestured to the middle distance. Among the milkweeds and goldenrod, the katydids would be singing. I found it almost impossible to distinguish any of these songs, but every now and again she would hold a finger to her lips and follow some pitch to a blade of grass. Often the first katydid she found was a silent female who had also been creeping on the song. Then we’d sit very still waiting until the male forgot us and resumed his chirping. Farther off, my friend could make out a catbird mimicking, sometimes the traffic, sometimes the hum of insects.

Although I nodded along, trying to be in the same moment, the truth was I could only hear the crescendos and diminuendos of a single huge song, while my friend drew one strange creature after another from the field and set them on my hand so I could admire each for a moment before they leapt once more into the chaos of chirping and wind-rustled grasses.

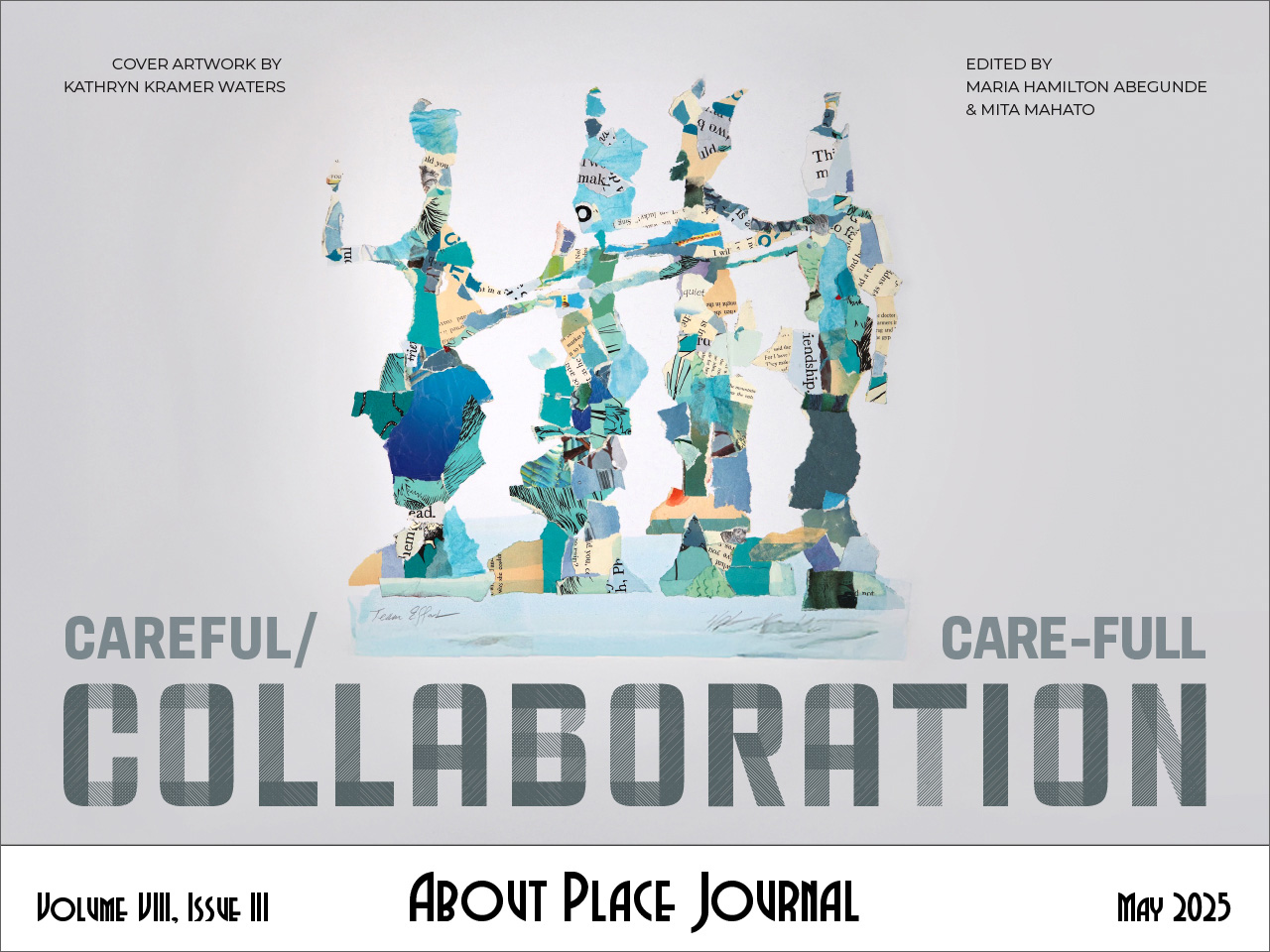

Kathryn Nuernberger has been researching and writing about symbiotic mutualisms for many years. During a residency for artists, writers, and scientists on a ship to the Arctic Circle, she met Sarah Nelson, who has been drawing instances of symbiotic mutualism for many years. Their work has become, at times, beautifully entangled, as their friendship has grown. These writings and illustrations were developed thanks to a grant from the Office of Research and Innovation at the University of Minnesota, which

encouraged cross-pollination among artists and scientists. The grant also enabled them to work in conversation with animal behaviorist Dr. Marlene Zuk to learn more about her research on the ways an unusual group of silent crickets find each other and how this research led her to lava crickets, which, you might say, are symbiotic with lava and the green world that they together make.