Reservoir Moon – Our Ninth Swim

We chose the reservoir because of the moon, September’s second moon.

An extra radiance tacked on to the idea of month

that once meant one moon only.

Maybe from the reservoir we’ll see it coming up, maybe we’ll swim in moonlight

or maybe it will simply be another cloudy night.

We have been waiting for this. Our first swim together in the dark.

Here in the now of what was once a flat and swampy valley floor.

Once inhabited by a group of Kalapuya. The Chemawala.

Now, land covered by water, controlled,

high in summer for irrigation, low in winter

so it may fill when rain is torrential,

when rivers overflow.

A world now for birds, boaters, water-skiers.

But what’s been drowned?

The sun goes down.

Gold gold gold. By the time we arrive, it’s gone.

No moon yet. The rutty parking lot. The paved road leading into

a gathering dark. The stained sky, orange and red. All the rest in black.

Where will we enter? Or did we enter the moment we left the car?

A dam as old as our mothers lies fifty miles east

of the Cascadia Subduction Zone,

a megathrust fault along the Oregon coast,

where one giant plate of the earth’s carapace

rubs against another. Potential earthquakes,

colossal, could go on for days.

The last shook here three-hundred years ago. The next, who knows?

We pick our way down to the reservoir’s edge. Still no moon.

We cannot see the line between water and shore.

It’s concrete, steep. Slick.

No. This is not a good place to swim. Let’s go back to the beach, even though

a point of land obscures the moon’s doorway.

Maybe we’ll swim in the dark and see the moonlight later.

A wave of disappointment. The clouds obscure our view.

Still, we have darkness and water and our bodies.

It’s easy to strip down in the dark, but this is the slimiest water yet.

Slimier than the Meditation Pool where debris from fire coated skin?

Slimier than McCredie and its puffs of silt?

Maybe the dark makes us feel it more.

Slippery. Almost oily.

Why do we feel the grime of people in this water? Because of its parks? Yacht clubs?

Because it is a reservoir? Human made? The Long Tom River swollen by a dam?

We slide into this greasy water that has washed the skins of thousands, lapped at the hulls of boats, absorbed runoff from farms and oversized new homes. Yet swans winter here. Land is lush with pheasant, quail, goose and dove. Corps of volunteers plant corn, millet, sunflowers by the thousands to feed migrating birds.

We are near each other in the water. Companionably close. But we do not touch. Into the water’s darkness, we disappear. All except our pale faces.

How long do we bob around? It’s cold. We feel unclean. Why do we stay?

The moon! It appears. Immense and orangey, rising behind the distant hills.

Not visible from the beach, but we have swum into its moonview.

It floats higher, luminous, like an old guardian, sending gleaming ladders across the reservoir.

Or are they ropes? Waving, inviting—

Umbilical cord

tender, tremulous thread

linking our bodies to the moon

fat silky sky womb

Womb and veins and arteries, how we love to see the world in our image…the world holds us in its body, we hold the world in ours. Messy, wounded, alive. Long Tom, we’ll speak your tributaries, from source to mouth in all their tainted names: Michaels Creek, Jones, Swamp, and Dusky, Hayes Creek, Sweet Creek, Green and Gold. Noti, Wilson, Indian Creek and then—after the reservoir: Squaw Creek, Coyote Creek, Lingo Slough, Bear. Amazon, Ferguson, Shafer Creek and Miller. And you all together join the Willamette, and you all join the Columbia, and you all join the sea.

Reflections

Swimming in the dark, what we didn’t see –

crappie, bass, bluegill, bullhead, warmouth, carp, heron, blackbird, hawk, martin, tern, kite, eagle, tern, stilt, swan, mallard, teal, teal, shoveler, wigeon, pintail, gadwall, scaup, duck, bufflehead, duck, canvasback, duck, duck, merganser, goose, grebe, grebe, grebe, bittern, rail, coot, snipe, phalarope, pelican, sandpiper, sandpiper, sandpiper, plover, plover, killdeer, yellowlegs, dunlin, dowitcher, sandpiper, plover, plover, avocet, willet, whimbrel, curlew, godwit, sanderling, ruff, dowitcher, phalarope, killdeer, sandpiper, dunlin, yellowlegs, plover, chat, woodpecker, woodpecker, sparrow, deer, rabbit, squirrel, coyote, fox, porcupine, skunk, woodrat, weasel, shrew, vole, beaver, otter, mink, bear, elk, cougar, raccoon, opossum, nutria, bat, turtle, frog, butterfly, butterfly, butterfly

*

I think of paddling among the marshes by daylight. Western grebes, long-necked and elegant with their ruby eyes, diving without a splash, and reappearing—where? Impossible to predict. And pied-billed grebes, small and unassuming, barely diving at all, sometimes simply sinking until they disappear.

*

The sound of a bittern like an enormous water jug tipping, glugging out its liquid, or someone gulping a goblet of sky. A spring and summer Fern Ridge sound. Are there still bitterns gulp-glomping in the reeds of now? We are too far away to hear them.

*

Who passed this way before us? What marks did they leave on the land before it was covered with reservoir? Before creation of this artificial body of water? Six prehistoric sites occupied by humans have been found on the floor of Fern Ridge. Carbon dating indicates that people lived here and left behind traces of food, work, and shelter as many as 10,000 years ago. A temporary warm-weather shelter, alongside hammerstones and an anvil. Twenty-one earth ovens, and the charred remains of camas bulbs, hazelnut, and acorn husks inside them. Remnants of thimbleberry, choke cherry, Indian plum, and Miner’s lettuce. A lovely menu.

*

Fern Ridge Reservoir now covers 12,000 acres—what used to be river and marshland. It drops by three feet during irrigation season. Which means the wildlife living in these wetlands must adjust to significant changes in water level. By now there are probably organisms that anticipate the annual induced fluctuations, much as intertidal life has adapted to the ebb and flow of tides. There are probably other human patterns non-humans notice: busy human weekend days versus quiet weekdays. Hunting seasons. How many other predictable patterns do we have?

*

The U.S. Corps of engineers built a small island in the middle of Fern Ridge Reservoir because Caspian terns were eating all the young salmon at the mouth of the Columbia River. To protect the fish, workers hoped to move the tern colony to other places, including Fern Ridge. To encourage nesting on the island, the Corps installed tern decoys and sound systems broadcasting their cries. The birds visited the island but never nested there. Some wildlife resists human management.

*

Fern Ridge Reservoir occasionally experiences cyanobacteria blooms. Whenever this happens, we’re supposed to avoid swimming, water-skiing, power boating—any activities that might involve ingesting tainted water. Dogs and other animals can die within minutes after drinking the water, licking their fur, eating the scum along the shore. Strange to think how vulnerable we might be, even when the water feels sheltering, and dark and soft as velvet.

*

Good thing we didn’t drink it—agricultural runoff is an additional problem. The state just sued a local horse stable after discovering a 200,000 cubic foot mound of horse manure on the edges of the reservoir. The mound was the equivalent of three football fields filled one foot deep with manure! The owner of the shit heap was dismissive, pointing to the many septic tanks in rural parts of the county that generate massive amounts of waste water. As if one source of toxins justifies another.

*

I just can’t get his face out of my head. He looked so scared. The calm, relatively shallow waters of Fern Ridge can be deceptive. Hard to imagine drowning here—nothing like the powerful currents of the Rogue River, the riptides of the Pacific. But water can be choppy and dangerously cold. And people die here. Most recently a 17-year-old boy who didn’t know how to swim, and a 26-year-old man who did not resurface after diving from his boat. People who simply slipped beneath the surface and never came back up for air.

*

Once, paddling among the reeds at Fern Ridge, I saw enormous fish, their gaping mouths surely large enough to swallow an arm or a leg. Giant carp. I imagined disappearing down the drain-throat of a fish and ending up in some other, slimy world. Why did I not worry about carp in the dark? Why did I not worry about anything?

*

Night swims are so secret. We feel even smaller, even more invisible. As if we could become the water we swim in.

*

As a child I’d swim at night in the phosphorescence of the Atlantic—sequined stars both above and below. Here at Fern Ridge, before the moon has risen—there is similar suspension of up/down, top/bottom. Where is the line between inky water, inky sky? My eyes adjust to the night. Dark air slips over my body like the nightgown I put on each night to cover myself. But no black silk is needed here. My nakedness means nothing. I am all shadow and dusky flesh.

*

This year, before my wedding, my daughters threw a bachelorette party and invited a dozen young friends to swim with us at Fern Ridge. We arrived after dark, in the back of a beat-up old pick-up truck, full of rowdiness and wine. The caretaker heard us and sent us away—the park closed at sundown, and it was nearly midnight. We parked near an inlet, an unbeautiful spot near the edge of the road, and for a few minutes, everyone stood around and kicked gravel. But then my daughters tossed off their clothes, and plunged through the reeds and into the oily, purplish water. My body was twice as old as anyone else’s, and I was hesitant. But I knew my daughters needed me to love my body, so I slipped out of my sundress and climbed in. Cars zipped by, and everyone stripped down to nothing, splashed into the warm, brothy liquid. Soup! shouted my youngest. We’re a big pot of soup!

*

Travel outfitters offer night swimming deals to tourists. It seems strange to monetize something so intimate as bodies in water and darkness. Wrong to pay money to give ourselves over—held by the night and whatever the water, in its darkness, gives back.

*

Harvest Moon

Barley Moon

Nut Moon (Cherokee of the Carolinas)

Little Chestnut Moon (Creek of Alabama and Georgia)

Corn Maker Moon (Abenaki of the Northeast)

Moon When the Corn is Taken In (Pueblo of the Southwest)

Corn is Harvested (Zuni of the Southwest)

Middle Between Harvest and Eating Corn (Algonquin of the Great Lakes)

Rice Moon (Cheppewa and Ojibwe of the Great Lakes)

September’s full moon goes by many names, depending on who we are and where we live (and what we grow). Corn is a recurring theme for this moon, but more generally it marks the space of anticipation between harvesting and eating one’s work.

What should we name this September moon?

Rump Moon, Belly Moon, White-Breasted Moon. Left-Shoulder Moon, Nose-Tip Moon, Laughing Chin Moon….

*

Astronomers say this month’s moon is fatter than usual—a super moon that’s also partially eclipsed. Astrologists say it’s a good time for purification rituals, for shedding bad habits and facing the truth about shortcomings. You and I drift together, our bodies gently bumping like buoys in the night. We confess our failings. We laugh at my vanity and insecurity, and again at yours. It feels good to touch these places of shared frailty. We float and float, our voices part of the reservoir soundscape, until our skins wrinkle and we begin to shiver.

*

Most Slavic countries celebrate some version of Kupala Night—an old tradition that involves bathing at night in rivers, lakes, and sacred springs. In many places, bathing was once forbidden, because evil spirits were believed to lurk in water. But on Kupala Night, these spirits departed, and swimming in water became not only safe, it magically cured bathers of illness. Kupala celebrations exist today more as staged ceremony than authentic pagan ritual. In addition to night bathing, people wash their faces with dew from the Kupala tree, light bonfires and jump over them, sink tree trunks in water, and burn stuffed dolls. These rituals symbolize the union of fire and water, masculine and feminine. Observing these rituals ensures happy marriages, robust lovemaking, and the delivery of healthy babies plump as moons.

*

What are our rituals? This is our ninth swim together, and we reinvent ceremony with each new body of water: Some water we share with others. Some we have all to ourselves. Some water invites lingering. Some we scramble out of, quick and even graceless. But each time, we take our clothes off—no nonsense, no fuss—and move in tandem toward river, lake, pool or creek. We do not talk. We move with purpose, sometimes stealth. Even in water that invites leaps and splashes, we walk in, letting the water rise around us, feeling the disappearance of pubis, waist, and armpits. And then we float, defy gravity for however long we choose to stay.

Fern Ridge Reservoir

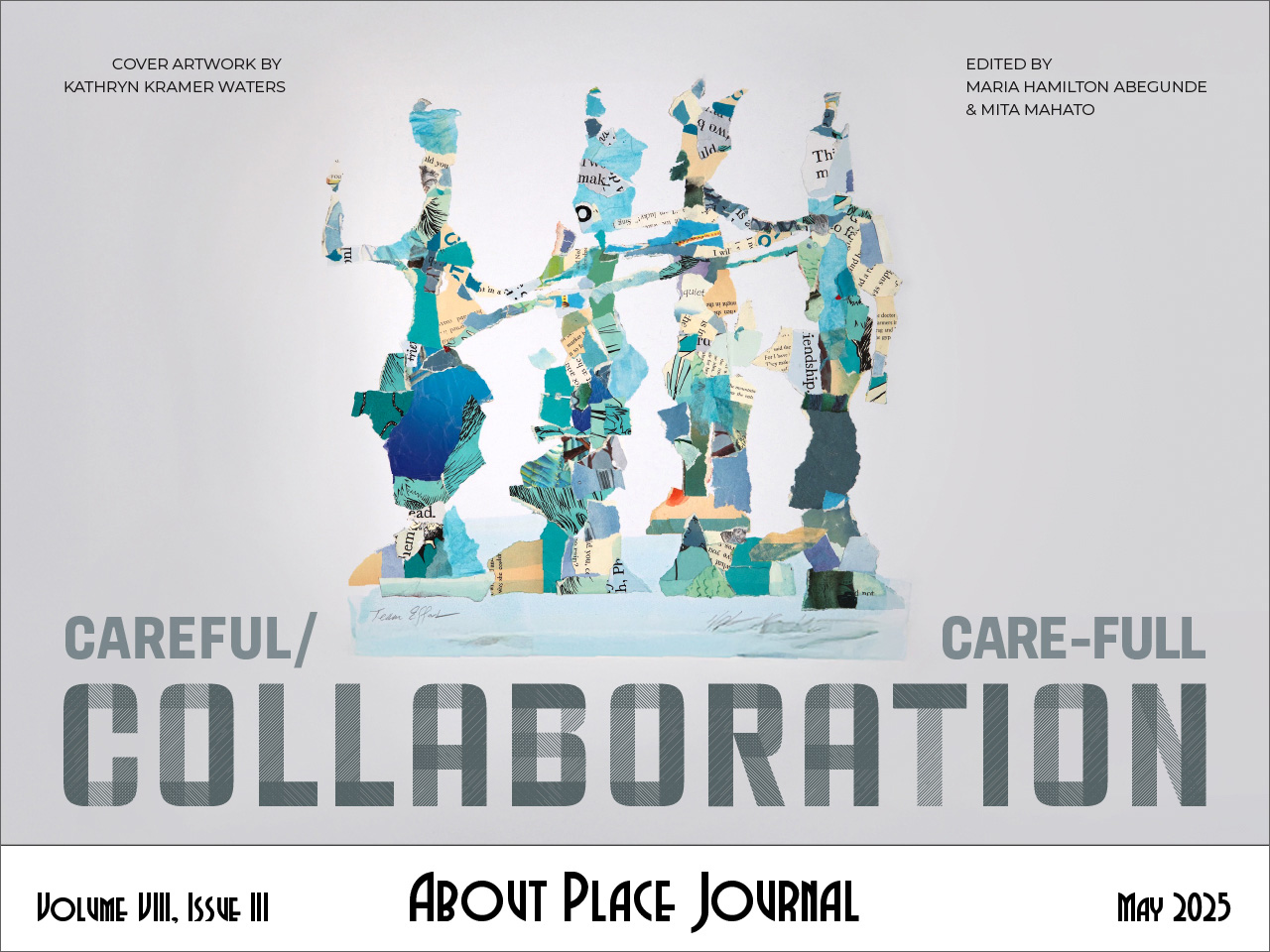

The above is an excerpt from our book-length manuscript, Water Questions. It includes a co-written description of our swim at Fern Ridge Reservoir and our reflections on what we learned about the place.

Our project was to immerse ourselves in twelve bodies of water over the course of a year. Our immersion was literal. We visited each body of water and skinny dipped for as long as our bodies could bear it. Our immersion was also figurative. We gathered information about the ecology and human history of each place: Who were the plants and animals who called this water home? Who were the people who named the water, lived beside it, laid claim to it over the years? What were the myths and lore that would help us understand the spiritual significance of each body of water—dune lake, river, thermal pool, ocean?

We wrote about our experiences in the form of “water letters.” And we supplemented our letters with photographs, drawings, and reflections that wove together all we gleaned from our research. Exposing our naked bodies to creeks and disappearing lakes, and also exposing ourselves to the forces that shape them—wildfire, drought, pollution, human use/abuse—deepened our intimacy with each body of water.

The importance of asking questions, both answerable and unanswerable, was central throughout: How does immersing ourselves in a body of water change us? How does immersing ourselves in a body of water change the body of water? How does collaboration transform us and the messy web of connections among ourselves, each other, and the places we visit and write about?

When we first began this project, we didn’t know a lot about each other. We grew up in the same small lumber town, perched on rickety stools in the same high school art class. But we hadn’t crossed paths for 40 years. By skinny dipping and talking—lots of talking, on the way to the water, on the way home from the water—we bared ourselves to one another, grew intimate with one another. We discovered differences as well as points of overlap, grew familiar with the other’s naked body and habits of thought. And as we spent time with each body of water—wading into winter rivers, basking in sulphured springs, plunging into chilly mountain lakes, and devouring all the information we could find about these places—we more fully appreciated their beauty and fragility along with our own.

Our collaboration is like playing a game with a friend, the kind where you invent the rules as you go: How about this? What if? Let’s try…. Ideas bounce and proliferate between us. Sometimes one person flags, doubts. The other rebounds with fresh excitement. The next time, the roles reverse. We enter water together that we wouldn’t, alone. We enter writing together that we wouldn’t, alone.

We try writing separate accounts. We try writing to each other. We try written conversation. We try writing the same piece at the same time, passing it back and forth. Sometimes one wants more order, the other flexibility. Sometimes the passions of one are not the passions of the other. We talk out loud. Structure, pattern, shape.

Revisions are harder, moving toward something final, something other people might see. Now we become self-conscious: My voice? Your voice? My truth? Your truth? Now we must be even more careful, balancing approaches and vulnerabilities. Who gets to say what? We both want to describe the toads … are we repeating ourselves? Or deepening the description? One makes a general statement about us. That’s not me, says the other.

We have to decide together: When does a passage become we? When does it reflect an individual I? We are braiding two voices, like a song. Sometimes in unison, sometimes harmony, sometimes counterpoint, sometimes a curious, even beautiful dissonance. We try to make room for them all. And we realize that sometimes each of us makes assumptions without knowing we are making assumptions. Collaboration helps us see the unseen, two ways of being.

Our story has two protagonists rather than one. Neither of us wants to be foil to the other’s hero. Our perspectives jostle for attention. Like rivers and streams, our viewpoints are sometimes converging, sometimes forking. We both worry about coming across as less sympathetic, less interesting, less compelling than the other. As we negotiate the way the other represents us, we struggle at times. Regain our footing by talking things through—tending to one another’s anxieties—and always returning to the water.

Swimming—skinny-dipping in particular—makes us vulnerable, humble even, and more alert to our surroundings. We notice the presence or absence of other people. The angle of the sun. The texture of the ground underfoot. The appearance of the water—murky, clear, moving, still. Signs of pollution, strength of current. Things we might not otherwise notice become important when we think about baring ourselves and going in. Now we’re attentive to these qualities of water bodies even if we don’t enter them. Often the water is very cold. We can’t stay in for long. But even a quick dip leaves us tingling, awake. And it feels as if we have made a small pact with the place—and by extension, other places like it: we are in this together. Meaning life on earth. Our swimming adventures in wild places continue to remind us that we are part of every landscape we enter.