How do our movements create resonance(s) between us?

Resonance. I am thinking about insects. Their buzzing, winging, rubbing, clicking, scurrying fill my ears.

At its most fundamental, “resonance” means sound again. Sound again. It captures a call and its response, which is the call again. Sound and sound. It follows that “to resonate” carries the meaning “to remind” or “to be similar.” Insects sound and sound in a field. “Resonance” also means “persistence.” To have resonance is to be lasting with sound. Sounding again and again. Sound with each other again and again. Persistently echoing insects. Not repetition, but resonance.

I am thinking about insects because after reading the contributions in this section, grouped together for what they say about resonance as care-making, I am taken by the number of insects that show up—crickets, katydids, beetles, and locusts among them. Insects sound off in Erica Waters’s poem “Orchestra,” in which a cricket’s stridulating legs echo sparrow song, which echoes cymbal spill, which echoes dog bark. Kathryn Neurnberger’s flash fictions feature katydids, crane flies, and lava crickets. The insect images in Sarah Nelson’s looping animations, which accompany Neurnberger’s words, twirl and tumble and glow, both taunting and nudging the desire for entomo-embodiment expressed in the fictions. In Nancy Takacs’s poem “A Whispering Beetle,” she writes, “I am like this beetle,” spinning from there a delicate reflection that listens for entangled place. And Jeffrey A. Lockwood and Mohamed Abdellahi Ould Babah E. Horma Abd Eljelil offer tender dialogue on their collaboration across time and distance, born out of their mutual passion for acridology, the study of locusts and grasshoppers.

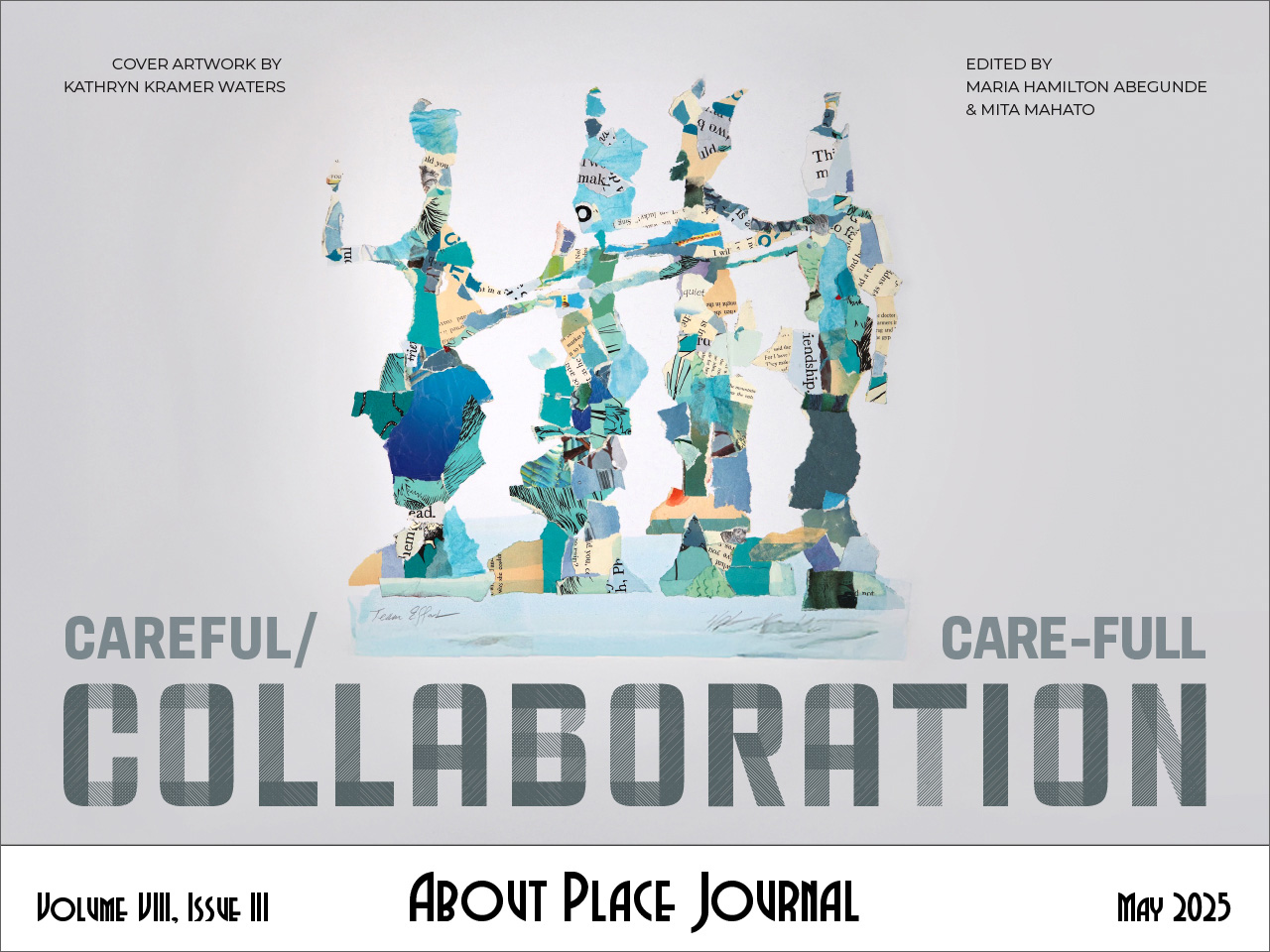

Resonant insect life here is not about transfiguration of one kind of being into another, as in Cronenberg’s The Fly or Kafka’s Metamorphosis, but rather the interfaces and intersections of being—six-legged or two or however we make our movements toward and with each other. It is Isabelle Stenger’s “reciprocal capture,” re-sounded by Deborah Bird Rose as “a process of encounter and transformation, not absorption, in which different ways of being and doing find interesting things to do together” (G51). This doing is not just with insects, then, but involves all our generative, careful entanglements. In this resonating field that buzzes and chirps, that listens and sounds back in order to persist, I also hear the tearing of paper, scattered and gathered in community collage; a glass candy dish clinking against its cover to reclaim a body as a place for pleasure; the re-sounded voice from an answering machine in mournful call and response; spirit and science harmonizing throughout. The resonance of beings moving with beings.

There are insects in the other sections, too—as well as arachnids, worms, all kinds of birds, imagined creatures, and so many humans collaborating with paper, pen, needle, thread, pixels, paint, and, foremost, care. Listen: The whole field is abuzz. Can you hear it? Listen again: The whole field is abuzz. What do you hear now? And now?

____

Sweet honey gratitude to Abegunde, Matty, Kate, Michael, and Jesse. Thank you for this buzzing hive.

____

Work Cited:

Rose, Deborah Bird, “Shimmer: When All You Love is Being Trashed,” Arts of Living on a Dying Planet. Eds. Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan. Nils Bubandt. Minneapolis: U of M Press, 2017.