Stephen Wilbers

“Poetry was likely song at first, before it was written down.”

– Heid E. Erdrich[1]

I met artists MaryBeth Garrigan and Petra Johnita Lommen[2] in the fall of 2023 when they shared some of their avian night sky paintings on a Zoom meeting of Starry Skies North,[3] a nonprofit organization devoted to reducing light pollution. They explained they were planning an exhibition of their avian art for late June–early July 2024, and they talked excitedly about the mystery and beauty of our dark starry skies, as well as how light pollution interferes with avian migrations, feeding, and breeding.

My collaboration with the two artists began after musician Jerry Kosak had already set their paintings to music. When I arrived at the Schmidt Artist Lofts west of downtown St. Paul to see more of the paintings, the two painters did more than welcome me with open arms.[4] They embraced me. They spent hours talking with me about their artistic vision and showing me their paintings, many of which are displayed on the walls and corridors throughout the beautifully transformed concrete, stone, and brick brewery where they live and where they share a large studio with other artists.

The idea behind my part of the collaboration was that my poems would illustrate their paintings rather than their paintings illustrate my poems. The more I kept going back to the Schmidt Artist Lofts and talking with the artists, the more their paintings took on the warmth and familiarity of old friends. I soon realized that my poems must always be, not secondary exactly, but ancillary, in service to their art.

With my poems drawing attention to their paintings, and their paintings drawing attention to the mystery and beauty of the starry night sky, my concept of our collaboration began to expand in purpose. It moved beyond appreciating the solace and beauty of the natural world to limiting light pollution for the safety and survival of nighttime migrating birds, to mitigating the extraordinary damage our species is doing to our climate and our planet, and from there to a broader defense of art, beauty, science, and technology, and finally to a vision of a world in which social justice is assumed.

The poems and the paintings

My poem, “Alphabet of the Trees,” was inspired by their mesmerizing painting, “Whispers of the North.” It was shaped, both literally and figuratively, by the poetry of William Carlos Williams,[5] a poet I admired and studied as a graduate student in Iowa City during the tumultuous 1970s. Two of Williams’ poems in particular have never let go of me.

Have you ever noticed how an “alphabet of the trees” is revealed when autumn leaves fall? In “Botticellian Trees,” Williams depicts how spring foliage “pinches out” those “letters that spelled winter,” and how that foliage replaces the silent letters of the alphabet, “quick with desire,” with something perhaps more alluring.

The second Williams’ poem, “The Red Wheelbarrow,” begins

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

Note how Williams’ line breaks shaped my poem, “Alphabet of the Trees.”

Alphabet of the Trees

after William Carlos Williams’ “The Botticellian Trees”

On a cool autumn day turned dark starry night

the great gray watches us and we watch it,

one of us fading to the other, the other

shining bright as the newborn sun.

It was then that one hungry

owl, silent as the stars,

swooped down on

one unlucky squirrel

who failed to spot those talons, who

missed seeing those two descending arcs of white.

Look, they say. And sing with us our winter song.

It was then that letters hidden in the alphabet of the trees,

arising with the death of the brown muffling leaves,

spelled out the living beauty of winter’s cold,

and there arranged in piercing trinity,

those eyes, watching, waiting, un-

believing, commanding us to

stop, think, move, or die,

to listen to their song

of humankind’s un-

kindness,

to understand,

to read with naked eye,

the story of our quick desire.

Now find one dark reproachful eye

beneath a crossing bar of swollen limbs,

hidden yet illumined behind those gray letters.

Look, they say. And sing with us our winter song.

When I asked MaryBeth and Petra, what if I write something you didn’t intend in your paintings, they said go for it. Every viewer brings their own thoughts and experiences and emotions to a work of art. That’s what the artists and I hope everyone does as they experience our collaboration. Go anywhere your imagination takes you.

Speaking of which, did you see that “dark reproachful eye beneath a crossing bar of swollen limbs”? When MaryBeth first read this poem, she said, “I didn’t know that eye was there!”

Touched by an artist’s hand

As MaryBeth is quick to tell gallery viewers, she’s not interested in painting pictures that look like photographs, though she’s certainly capable of photo-realistic art. “I want the human touch,” she says. “I want my paintings to look like they were created by an artist’s hand.”

When I asked Petra about the dark night sky, she said, “The first time I looked up at the star-studded sky of the Boundary Waters, I was overwhelmed. The starry night sky’s extraordinary beauty and mystery will always be with me.” Then she paused and said in a low voice, husky with emotion, “It’s part of who I am.”

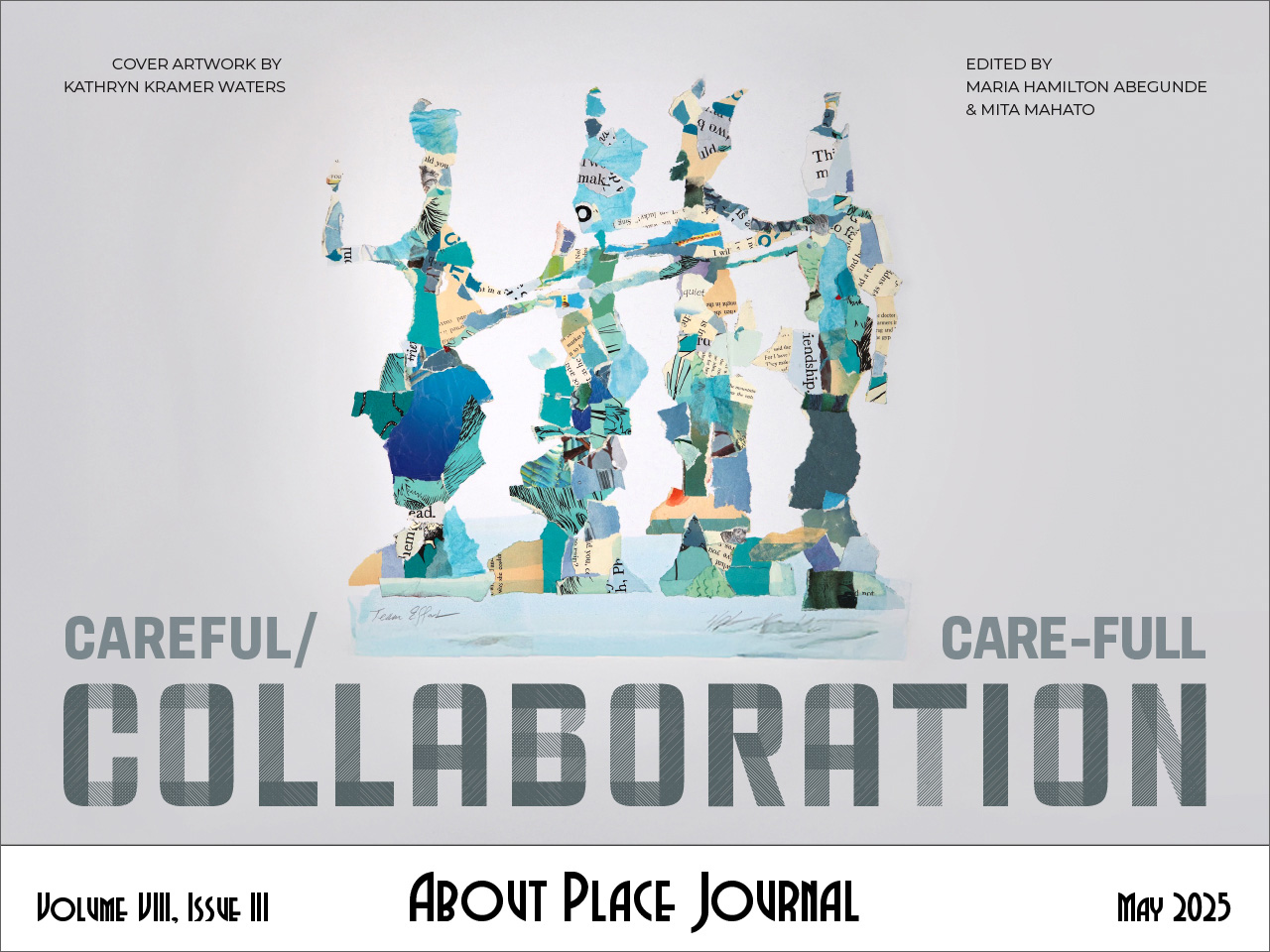

The poetry panels and the paintings

It was MaryBeth and Petra’s idea to mount my poems on panels large enough to be read from a distance. Our hope was that the poems might encouage viewers to pause and take a second look at the paintings, to linger more than four or five seconds and really look at a painting that took weeks or months for the artists to create.

What they were suggesting was that my poems be treated as physical works of art, displayed in prominence equal with their paintings. Imagine being invited to join a collaboration imbued with such generosity of spirit.

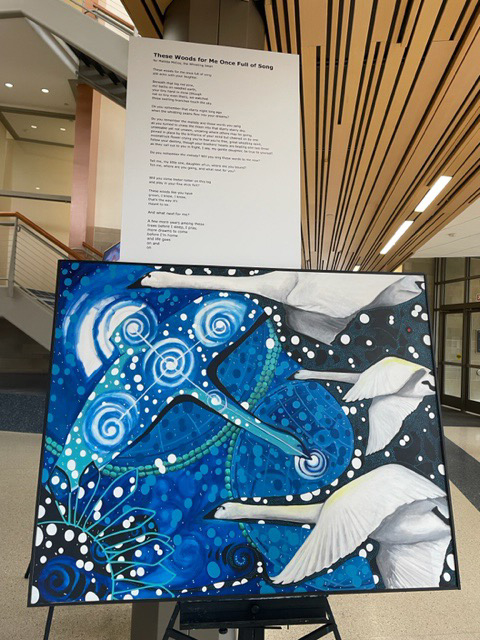

For the love of the whispering swan

MaryBeth and Petra’s painting “Cygnus Homage to the Children of Lir”[6] is one of my favorites (though I love them all).

Both their painting and my poem, “These Woods for Me Once Full of Song,” were inspired by one of the best-known myths in Ireland. It’s about the beautiful and free-spirited daughter of Lir, who along with her three brothers was condemned by her jealous stepmother Aoife to live three hundred years as a swan. I dedicated my poem to my free-spirited twelve-year-old granddaughter, Matilda McCoy,[7] whose whispering wingbeats can be heard as you pass by the billabong. Believe me, she needs no encouragement to follow her imagination to the heavens.

These Woods for Me Once Full of Song

These woods for me once full of song

still echo with your laughter.

Beneath that big red pine,

our backs on needled earth,

your tiny hand in mine (though

not so tiny even then), we watched

those swirling branches touch the sky.

Do you remember that starry night long ago

when the whistling swans flew into your dreams?

Do you remember the melody and those words you sang

as you turned to chase the moon into that starry starry sky,

unseeable yet not unseen, uncaring where others may be going,

pinned in place by the brilliance of your mind but cheered on by one

moonstruck flower crying you’re free you’re free, great whistling spirit,

follow your destiny, though your brothers’ hearts are beating one two three

as they call out to you in fright, I say, my gentle daughter, be true to yourself.

Do you remember the melody? Will you sing those words to me now?

Tell me, my little one, daughter of Lir, where are you bound?

Tell me, where are you going, and what next for you?

Will you come teeter-totter on this log

and play in your fine stick fort?

These woods like you have

grown, I know, I know,

that’s the way it’s

meant to be.

And what next for me?

A few more years among these

trees before I sleep, I pray,

more dreams to come

before I’m home

and life goes

on and

on

“The moon’s on its way to its nightly shift”

My poem, “Away but Never Gone,” was inspired both by the painting, “A Lunar Eclipse for MaryBird,” and by The Wailin’ Jennys’ hauntingly beautiful song, “Away but Never Gone.”[8] Petra did her painting as a gift to MaryBeth, who also goes by MaryBird, so I wrote my poem as a love poem for my wife Debbie.

Before or after you read it, I invite you to listen to the Wailin’ Jennys’ haunting melody. Its easy, slow rhythm and gentle, captivating lyrics animated my poem. I can almost hear the sound of that nest as it “rustles high on a bough,” can almost feel “the blue egg” staying warm “In the cool of the morn/Under a red breast of down.” Can you hear the pulse of those lines? As with Williams’ poems, their rhythm and flow won’t let go of me, and so, with variations on the original, I wrote, “Winter comes on/A lifetime goes by/. . . below a dark shimmering sky.”

Not for the first time, I’m struck by the intersection of song and poetry as a kind of collaboration. I think Minnesota Poet Laureate Heid E. Erdrich would agree. “Poetry was likely song at first,” she said, “before it was written down.”

Away But Never Gone: A Love Poem

after the song by The Wailin’ Jennys

Winter comes on

A lifetime goes by

Reflections on still water

below a dark shimmering sky

Your laugh in the crunching leaves

stars spinning and twirling their limbs

The blood moon holds me in its spell

as it moans its low sweet song

To see the earth move along its way

to perch on the wings of a hawk

to catch one last leaf as it zags

zigging to the ground . . .

to be in love with you

A meeting of minds, hearts, and souls

In the run-up to our spring 2024 exhibition at the Schmidt Artist Lofts, we took our avian night sky multimedia show on the road when we displayed our paintings and poems at the March 2024 St. Louis River Summit[9] in Superior, Wisconsin, a conference dedicated to sharing research on the successful decades-long effort to remediate, restore, and revitalize a badly polluted river feeding into Lake Superior.

When I presented a slideshow of our avian paintings and poems at the 2025 Summit, I experienced a remarkable cross-disciplinary, cross-cultural collaboration, one that featured a mosaic of scientists, teachers, students, community leaders, and artists, both Native and non-Native, in a welcoming atmosphere of shared research, ideas, values, and worldviews on topics ranging from treaty rights to algae blooms and sustainable aquaculture production. It was an amalgamation of head, heart, and soul, or in Aristotle’s words, an appeal to logos, pathos, and ethos.[10] To be fully persuasive, the philosophers and classical rhetoricians say, you must appeal to the whole person. You must connect not just with the head and not just with the heart, but with all the components that make us human. I felt a similar inclusivity at the St. Louis River Summit, one that was felt and witnessed by all who had gathered. It was a feeling akin to the coalescence of spirit and viewpoint I am experiencing in my collaboration with MaryBeth and Petra.

Collaborating across boundaries and genres

When I look at “Mysteries of the New Moon,” I see swirling energy, a roaring conflagration, and rising ashes.

What do you see?

Their mesmerizing painting inspired my next poem, “Have Faith in the Blues of the New Moon Rise.” That poem has at least four other sources of inspiration, representing a kind of multimedia collaboration. It was also inspired by Native photographer Travis Novitsky’s Spirits Dancing, by climate activist Terry Tempest Williams’ online essay “Believe,” by WOJB’s “Blue Monday,” and by the poetic expression of Minnesota poet, essayist, and fiction writer Barton Sutter, who has served unwittingly as a kind of musical and spiritual mentor to me for the past 45 years.

Travis Novitsky and Annette S. Lee introduced me to the concept of “two-eyed seeing,” or “etuaptmumk,” which Novitsky and Lee describe as a “guiding framework” for their amazing book of photography, Spirits Dancing.[11] Mi’kmaw elders describe “two-eyed seeing” this way:

Learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of Western knowledges and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes for the benefit of all.

The second additional inspiration for my poem was Terry Tempest Williams’ brilliant online essay “Believe,”[12] in which the climate activist describes the “blast furnace” heat that is rendering Utah increasingly inhospitable to human habitation. To capture the essence of her essay, allow me to shape-shift from prose to poetry:

I feel the roiling hot energy of our plundered planet,

and although Tempest Williams implores us

to go beyond hope and do something,

I nevertheless “reach for the cool

of [those] last bright stars,”

and I “cherish all

that remains.”

And don’t you think it’s cool as hell that a climate activist has Tempest in her name?

The third additional influence for “Have Faith in the Blues of the New Moon Rise” was the blues. The blues beat came to me while listening to “Blue Monday” on Woodland Community Radio WOJB, a radio station broadcast from the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation southeast of Hayward, Wisconsin.[13] As I was putting the finishing touches on my poem, I unconsciously incorporated a blues beat into the rhythm of my words, and then realizing what I had done, I repeated a verse as a refrain.

Then with the blues still on my mind, I asked musician friend and composer Don Browne if he would put my lyrics to song, which he did. And when Don and his band Fireroast Mountain Boys[14] performed our song at a Minneapolis dance club, I was thrilled. Again, what could be more natural than poetry, music, and song?

Which brings me to the fourth additional inspiration for my poem (and for my poetry in general): a writer I have long admired, Barton Sutter,[15] three-time winner of a Minnesota Book Award. I love the way Bart moves seamlessly from relaxed colloquial speech to carefully wrought metaphor, occasionally dropping in a rhyme. I especially admire how he combines poetry and song at his readings when he sings with his brother Ross, interspersing delightful musical olios with the spoken word. Two brothers making music together. Poetry and song.

So inspired by the painting, along with those four points of inspiration pricking both my imagination and ears, I ended up with this poem.

Have Faith in the Blues of the New Moon Rise

after Terry Tempest Williams’ “Believe” in The Wings of Herons

come look at these stars to find out who you are

see the smile on the curve of my beak

hear the clack . . . clack clacking of spirits dancing

the beat of my raging heart

come perch next to me in this last dying tree

tuck your head in my soft nest of down

now awake from your greed and your easy sleep

feel the heat of your fiery new home

and look two-eyed at the spark-studded sky

face the facts of what you have done

come perch next to me in this last dying tree

tuck your head in my soft nest of down

go deeper than hope to transformative change

and move at the speed of light

open your soul to the blues of creation

have faith in the new moon rise

come perch next to me in this last dying tree

tuck your head in my soft nest of down

come back to your mother who loves and forgives you

and wrap your small ones in snow

feel the blast furnace breeze like a broken dream

watch my black wings burst into flames

come perch next to me in this last dying tree

tuck your head in my soft nest of down

then reach for the cool of these last bright stars

and cherish all that remains

Counting the stars in the sky

Like “Have Faith in the Blues of the New Moon Rise,” my next poem, “Sandhill Cranes Looking This Way and That,” was also written as a song. It picks up on the rhythm and images of Tom Paxton’s “Jennifer’s Rabbit.”[16] Both Paxton’s lyrics and mine are written in the tradition of Lewis Carroll’s and Edward Lear’s nonsense verse.[17] So I invite you to wait for a dark starry night and then run away from home with Jennifer’s rabbit, “Along with a turtle and a kangaroo,/And seventeen monkeys from the city zoo,/And Jennifer too.”

Naturally, my 10-year-old grandson, the not-so-little Lachlan Lee to whom I dedicated the poem, counted how many stars had fallen down to the ground in the painting, “Over the Tetons.” I’m not going to tell you how many, but the number is somewhere between one and “one trillion and four.”

How about you count and see? Along with Jennifer and Little Lachlan Lee?

Astronomers say that to fully appreciate the beauty, mystery, and wonder of the dark night sky you have to be able to count 400 stars with your naked eye.

Sandhill Cranes Looking This Way and That

after Tom Paxton’s “Jennifer’s Rabbit”

Little Lachlan Lee was sleeping in his little grassy bed

when four long-legged cranes alighted on his sleepy head.

Then two two-eyed raccoons descended from their sappy tree

to leave their cozy home and go exploring by the sea,

and so did Lachlan Lee.

The cranes ran through the grasses up and down the sandy hills.

They ran on sticky legs in search of sticky wicky thrills.

The more they roamed and ranged, the sorer they became.

So Little Lachlan Lee atop his favorite leggy crane,

said fly or you’ll go lame.

They shot up through the clouds to the moon so very high.

They flew so fast and far they knocked the stars down from the sky.

The mountains wrapped them snug and tight in comfy cold moonbeams,

and then they stuck their sticky legs in sticky milky streams,

awash in Lachy’s dreams.

By the sandy hilly hills where the wild cranes like to play,

an eager beaver paddled from a beamy moonlit bay.

Said the beaver, Lachlan Lee, who left these stars here on the ground?

And how many are there scattered all around?

How about we count and see?

said Little Lachlan Lee.

Stillness bursting with movement

Now that you’ve seen a few of MaryBeth and Petra’s pieces, I think you’ll understand what I mean when I describe their paintings as kinetic, something like a coil spring about to unleash its energy, or maybe more like the universe expanding without end (or maybe recoiling). When I wrote about action as stylistic technique in my book, Keys to Great Writing,[18] I pointed out how F. Scott Fitzgerald’s descriptions in The Great Gatsby are characterized by movement, that is, his “descriptions are not still photographs but moving pictures” in which “nothing is fixed; everything is in motion.” Note how Fitzgerald uses action and movement in this sentence to describe Gatsby’s “cheerful red-and-white Georgian Colonial mansion, overlooking the bay”:

The lawn started at the beach and ran toward the front door for a quarter of a mile, jumping over sun-dials and brick walks and burning gardens – finally when it reached the house drifting up the side in bright vines as though from the momentum of its run.

I feel the same movement and energy in MaryBeth and Petra’s art. Whether sitting in their apartment with their sweet little rescue dog Rooster nipping at my shoes if I move my feet unexpectedly, or threading my way through the maze of art-lined hallways, or basking in the pure white light flooding their studio from the skylight above, on each visit I am surrounded by dramatically posed avian centerpieces backgrounded by star-studded black acrylic skies, by roiling heavens flecked with swirling points of white and layered with red, purple, orange, and yellow waves of pure energy mixed with cobalt, azure, teal, cerulean, and sapphire shades of blue, all swirling around my head and whirling around my imagination long after I return home.

I wrote my next poem, “Hello to Summer,” with the idea of stillness bursting with movement in mind. It came to me as I was walking down a dark gravel lane on a moonless summer night in northwestern Wisconsin.

Hello to Summer: A Poem in Two Parts

Part 1: Crunching Down a Dark Gravel Lane on a Moonless Summer Night

Here’s how you walk down a dark gravel lane

on a moonless summer night

without bumping into

a tree.

It’s easy.

You listen to the gravel crunching beneath your feet,

and when it stops you know you’re in trouble.

If there’s any

light in the sky

(a glimmer will do),

you look up to where

those trees don’t touch,

and step by step you climb

those crunchy stairs to the stars.

You’ll be just fine, you tell yourself.

Don’t worry, you tell yourself.

It’s a painless journey.

No need for fear.

No need to give any thought

to other places you could be going

or where you might have gone wrong.

Just pay attention. Be present. Listen.

Part 2: Without Conscious Thought

Walking down a forked gravel lane,

I took the one more traveled.

It wasn’t my fault.

I was doing everything right.

I was alive to my present surroundings,

living my midsummer night’s dream,

the air cool and damp, the fireflies

twinking on and off, on and off.

But listen. Here’s the thing.

Fireflies don’t guide you

so much as mystify

and delight you

and maybe

inspire

you.

And that’s when it happened

on that moonless summer night.

Without choice of will, nor conscious thought,

my hand darted to that beast in my pocket,

its glaring screen blueminated my eyes,

my feet went yon rather than hither –

went that way instead of this –

and the ground went soft

and the crunching

stopped.

It was so quiet.

And in that encircling silence

with no whisper or trace of breeze,

I found myself transfixed,

the spinning world

at my fingertips,

and never

so lost.

Then just before

it was forever too late –

the cosmos forever dimmed –

I confined that beast to its lair.

And with fireflies flashing about me,

the Earth exposing her milky way,

I climbed that gravel stairway

into the starry night sky.

Coda

The Friends of the Eau Claire Lakes Area (FOECLA),[19] a Wisconsin lake association on whose board I serve, distributed that poem with a stock image of the starry night sky. That was before I had met MaryBeth and Petra. After meeting them, I asked if they might have an original painting I could pair with my poem.

“Here,” said MaryBeth, emerging from her back room with “Midnight Walk” in hand. “You can use this one,” she said.

“I painted it right after high school when I was working as a Bell Museum interpreter for the University of Minnesota’s Itasca Biological Station.[20] I had taken a midnight walk in Preachers Grove, and I was so moved by what I saw that I painted this when I got back to my room.”

“So, Petra,” I said, “if we’re going to feature that lovely night skyscape MaryBeth painted right after high school, it just seems right that we have a matching solo work by you. Do you have a companion piece we could include?”

“Well,” said Petra, “you know that painting you keep looking at, ‘Jingle Dress Starscape’? I painted that while I was working as Paleontology Hall floor supervisor at the Science Museum of Minnesota,”[21] she said. “One day on a walk I came upon a group of Ojibwe dancers, whose jingle dresses made this amazing otherworldly sound. That sound led me to see the relation between sound and stars in a way I had never before experienced, so I tried to capture that feeling in this painting.”

On a later visit to the Schmidt Artist Loft’s studio, Petra positioned her painting where the lighting was perfect. And then she said, “Here. I know how much you love this painting. It’s yours.”

As I realized what was happening, tears came to my eyes. Only later would she let me pay her for two other paintings.

That for me is the heart of collaboration.[22] Collaboration is more than creativity and commitment. It’s also kindness, generosity, and human decency.

I’ll conclude with a poem I wrote expressly for this article. It conveys my hope for our future, both yours and mine.

A Morning Prayer

Notes and Further Reading

[1] Heid E. Erdrich, two-time Minnesota Book Award winner and 2023 poetry chair for the National Book Awards, was appointed Minneapolis’s first Poet Laureate in December 2023. She views her appointment as an opportunity to remind people that poetry is everywhere – in songs and in prayers, in “language that moves people” by community members and by “people who use words in their visual art.” Source: “In song, prayer, first Mpls. poet laureate hopes to move city,” by Chris Hewitt (Minneapolis Star Tribune, December 20, 2023).

[2] Avian Night Sky collaborators include two artists, a musician, and a poet. MaryBeth Garrigan is the founding director of the National Eagle Center. She paints the birds. Petra Johnita Lommen often expresses her feminine mystique in her work. She paints the stars and swirling galaxies. Jerry Kosak is a composer and guitarist extraordinaire. He set our entire exhibition to music. And Stephen Wilbers is a former self-syndicated columnist whose poetry has been published by Red Dragonfly Press. He writes the poems.

[3] Starry Skies North and Todd Burlet, see final note.

[4] The story behind the Old Schmidt Brewery, the Schmidt Artist Lofts, and the artists, as told by biker Wolfie Browender.

[5] Poet William Carlos Williams’ poems “The Botticellian Trees” and “The Red Wheelbarrow.”

[6] The myth of the Children of Lir.

[7] Matilda McCoy, the Whispering Swan, waltzing with the troopers (one, two, three) above the billabong or watering hole in a bush ballad thought of as the unofficial national anthem of Australia.

[8] The Wailin’ Jennys and their song, “Away but Never Gone.”

[9] St. Louis River Summit, an annual conference in Superior, Wisconsin, celebrating the successful decades-long collaborative effort to remediate, restore, and revitalize the once severely polluted St. Louis River, which feeds into Lake Superior.

[10] Aristotle’s appeal to logos, pathos, and ethos, a persuasive strategy taken up by the classical rhetoricians who followed.

[11] Spirits Dancing, a book of northern night sky photographs by Travis Novitsky and Annette S. Lee.

[12] Climate activist Terry Tempest Williams’ essay “Believe” in The Wings of Herons.

[13] “Blue Monday” program, broadcast by Woodland Community Radio WOJB, a radio station broadcast from the Lac Courte Oreilles Reservation southeast of Hayward, Wisconsin.

[14] Musician and songwriter Don Browne and his band, the Fireroast Mountain Boys.

[15] Minnesota poet and fiction writer Barton Sutter and his sing-along brother musician Ross Sutter. Bart has served as an “unwitting” mentor to me in the sense that, other than my penchant for showing up at his readings, until recently he had no idea how influential he has been in shaping my poetic voice, this in contrast to my good friend Joe Paddock, who in so many meaningful and direct ways has served as my spiritual and poetic guide. It was Joe who during a writers’ retreat on a Rainy Lake Island (maintained by the Ernest Oberholtzer Foundation near the Minnesota-Canada border) challenged me to write one poem a week for 52 weeks, 16 of which were published on his recommendation by Scott King of Red Dragonfly Press.

[16] Singer Tom Paxton and his lullaby, “Jennifer’s Rabbit,” as they relate to the painting, “Over the Tetons.”

[17] Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, and nonsense verse.

[18] Keys to Great Writing: Mastering the Elements of Composition and Revision, one of Stephen Wilbers’ books on the craft of writing.

[19] The Friends of the Eau Claire Lakes Area (FOECLA), north of Hayward, Wisconsin.

[20] The University of Minnesota’s Bell Museum, its Itasca Biological Station (where artist MaryBeth Garrigan once worked), and nearby Preachers Grove of giant old growth red pines.

[21] Science Museum of Minnesota, where artist Petra Johnita Lommen once worked as Paleontology Hall floor supervisor.

[22] A 30-second video of MaryBeth Garrigan and Petra Johnita Lommen collaborating in their Schmidt Artist Lofts studio.

[23] Percival Everett, author of James (2024), a reimagining of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and winner of the 2024 Kirkus Prize and the National Book Award for Fiction.

[24] Big Jim and the White Boy (2024), another reimagining of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by writer, filmmaker, and award-winning journalist David Walker and award-winning cartoonist Marcus Kwame Anderson, who collaborated to create this graphic novel for young readers (and adults like me).

Protecting our night skies from light pollution

If you know someone who doesn’t think protecting our dark night skies from light pollution is important, you might encourage them to watch the 55-minute documentary, Northern Skies, Starry Nights, narrated in part by Travis Novitsky. (See note 11 for more on Travis Novitsky.)

I like to call this 55-minute PBS North/Hamline University documentary the “conversion piece” because it opens people’s minds, hearts, and souls to the luminous beauty of the starry night sky.

Here’s what you can do to avoid annoying your neighbors, polluting the night sky, and interfering with avian migrations, feeding, and breeding:

- Shield your lights,

- Install soft yellow rather than harsh white “blueminating” lights, and

- Put your outdoor lights on motion detectors or turn them off when you’re not using them.

Or as Starry Skies North President Todd Burlet likes to say, “Lights are like tools. Put them away when you’re finished using them.”

Todd Burlet was also the guiding force behind the establishment of DarkSky International’s newly formed chapter DarkSky Wisconsin, led by President Sam Saeger.