only the foolhardy

dare ignore

I am a Connecticut Yankee living in the king’s courtyard, otherwise known as deepest Arkansas. I live here by choice, but that choice has entailed certain compromises, such as droppin’ the final ‘g’ to soften my speech; strangers no longer accost me, sayin’, “Y’all ain’t from around here, are ya?”

Or perhaps they don’t say that because we’re no longer strangers.

Though I’ve lost a letter, I have not, I hope, lost the rocky soul of New England – the stories and the history and the love that bred me and fed me. It is one of these stories that has occupied my thoughts this past year.

hidden in the acorn’s heart –

it sprouts ever green

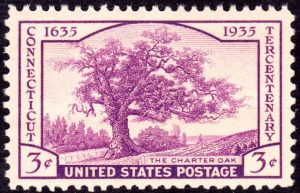

Connecticut’s State Tree is the white oak. Its image appears on the postage stamp and commemorative half dollar issued for the state’s Tercentenary in 1935 and, more recently, on the Connecticut State Quarter of 1999. White oak leaves and acorns embrace the seal on the state flag, oak leaves crown the seal of the Connecticut Judicial Branch and grace the center of the seal of the University of Connecticut… and they are engraved on the shell of my heart. Oak leaves, acorn, and the tree itself are symbols of freedom, independence, and justice that goes back to the seventeenth century.

The region that would one day become the State of Connecticut was settled in the 1630s by dissidents – people dissatisfied with life in the soon too-crowded and too-regimented colonies of Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth. Traders, farmers, churchmen and their families migrated to the woodlands to their south, walking along Native trails that wound through swamplands on the higher grounds of old beaver dams, that crossed rivers by the safest fords. They established communities that became the towns of Windsor, Wethersfield, Hartford, New Haven, and Saybrook.

The settlers were not invaders or conquerors. They were welcomed… indeed, invited… by Wahquimacut, Sowheag, and other sachems of various Indigenous Peoples living there – the Pequannock, Podunk, Saukiog, and Tunxis – who wanted European military prowess to protect them from their more war-like neighbors, the Mohawk and the Pequot.

whisper in the green shadows

of memory

These early towns soon formed three colonies: Saybrook Colony at the mouth of the Connecticut River, New Haven Colony facing central Long Island Sound, and Connecticut River Colony occupying the territories along inland waterways. The Massachusetts colonies were formed by Royal Charter granting them certain (though limited) legal rights to governance and business, but the colonies in Connecticut were not so authorized. While their citizens were loyal to the king, they minded their own business and carried on as best they could, governing themselves as they saw fit without benefit of charter.

live free, die unremarked

in the woodlands

Massachusetts didn’t care – the distances were too great to bother interfering with those disgruntled individuals who had left. Good riddance. Besides, as Governor John Winthrop of Massachusetts pointed out, Connecticut was “not fit to meddle with.”

Presumably King Charles didn’t care – soils were too rocky and harbors too shallow to make the region a profitable site for investment and trade.

The people of Connecticut Colony did care. They wanted the surety that a Royal Charter could provide. But the years of turmoil following the execution of King Charles I and rule by Parliament and Oliver Cromwell were not the time to ask for one. The right time came after the monarchy was restored and Charles II was on the throne. The freemen of Connecticut (that is, those men who were sufficiently prominent that they qualified to vote) feared the new king would put them under the control of Massachusetts or New York.

Spurred by this anxiety, colonial leaders wrote the charter for themselves. John Winthrop, Jr., Governor of Connecticut Colony and son of the man who said Connecticut wasn’t fit to bother with, took it to England. Charles II signed it in 1662… though I suspect he did not read it carefully.

The newly signed and sealed charter granted the colonists exceptional freedoms: the right to elect their own governor, not submit to one chosen by the king; the right to pass their own laws, not send them to England for approval or rejection; the right to hold their own General Assembly, not one that could be dissolved by royal decree; the right to buy and sell their own property, not be granted it subject to a king’s will or (dis)favor. And then, remarkably, Charles II let Winthrop take the charter back to the colony.

The charter could not be terminated so long as it remained in the colonists’ hands.

more fragile than the parchment

that breathes it

Twenty-five years and a new monarch later, King James II reacted to the increasing independence of the New England colonies by revoking their charters; by chopping away the colonists’ freedoms, one by one; by converting the semi-autonomous Charter Colonies to dependent Royal Colonies. Most surrendered their charters, returning them to England.

Not so Connecticut. The freemen did not rebel against the king – they remained loyal citizens of England and honored their sovereign. They just ignored his orders to return the charter.

In 1687 King James sent Sir Edmund Andros to assume control of the unruly colonies, giving him specific orders to seize the Connecticut Charter. On a dark October night in Hartford, Andros met with the colonists to discuss its surrender. Some say they met at Zachariah Sanford’s tavern, some say it was Moses Butler’s. The Governor of the Colony, Robert Treat, presided at the meeting. The charter sat in a box on the table between colonists and King’s men. Several dozen armed red-coated soldiers stood guard outside the doors of the building.

The outcome seemed inevitable.

The room was overcrowded and stuffy. A window was opened. A sudden gust of wind snuffed out all candles.

In the confusion, the charter disappeared.

The story is that Captain Joseph Wadsworth grabbed the document and ran to the yard of the Wyllys family where he hid it in an ancient hollow white oak tree. Governor Andros no doubt reported that the charter had been blown out of the window by the wind. In any event, there was no charter to be surrendered.

And there the legend ends. But the story continues.

A monarch’s power is absolute and not to be thwarted. King James decided he did not actually require physical possession of the charter to revoke it. He gathered the New England and Mid-Atlantic Colonies into one entity that he could more easily control: the Dominion of New England in America.

The Dominion lasted no longer than the King’s rule… both ended in 1689… and Connecticut restored its government under the old charter.

in patterns we cannot see –

cycles overlapping

At the time, the Charter Oak was truly ancient, ancient beyond memory. It’s thought that it had sprouted some five or six hundred years before it housed the charter. The Saukiog revered it as the “peace tree.” They had granted the newcomers the right to live near it provided they would never cut it down. That is one agreement the settlers honored.

In time, the old oak became a symbol of American independence, Connecticut’s Charter Oak. When the tree was blown down by a storm in 1856, it was honored with a funeral.

The colonists’ clandestine acts that October night in 1687 were not reported in a newspaper or town council minutes… there were no newspapers in the colonies at that time, and to write about such an event in official records would indeed be dangerous. King James would not have been amused. How do we know what happened? Over the years, on long, dark winter nights when the bitter winds howled around the eaves, old folks no doubt reminisced while young folks listened. When the young in turn became old, they told their children about the actions of their ancestors. Through such stories, yesterday’s events become tomorrow’s history.

In 1935, three hundred years after disgruntled colonists pushed through the forest to settle on Native lands, just about every city, town, and community in Connecticut celebrated the anniversary. A year-long series of speeches, parades, church services, pamphlets, musical programs, costume balls, and, of course, more speeches, marked the anniversary. Events were reported in the newspapers and broadcast on the radio.

But just what was it that the Tercentenary honored? Certainly not the land’s habitation by humans; Native Americans had lived there for more than ten thousand years. Nor its settlement by Europeans; Dutch Captain Adriaen Block explored along the Connecticut River in 1611, and his countrymen established forts some years before emigrants from Massachusetts arrived. No, the Tercentenary commemorated the arrival in 1635 of settlers born in England, settlers who displaced their predecessors.

the frosts of legend

we write our own history

Citizens of the State lobbied for a special postage stamp to honor the occasion. Then they lobbied for (or argued over) what should be depicted on the stamp: a map of the territory showing the earliest settlements, scenic views of one old town or another, the portrait of various historic figures. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Postmaster General James A. Farley viewed the suggestions. Finally, just one month before the intended date of issue, a decision was made. The stamp would show not the event the Tercentenary honored, but the Charter Oak and the event that preserved… at least for a while… the Colony’s freedoms.

The image on the stamp was based on The Charter Oak, painted by Charles De Wolf Brownell in 1857, shortly after the ancient tree was blown down. With a value of three cents, the stamp could deliver a first-class letter anywhere in the nation.

The image on the stamp was based on The Charter Oak, painted by Charles De Wolf Brownell in 1857, shortly after the ancient tree was blown down. With a value of three cents, the stamp could deliver a first-class letter anywhere in the nation.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing worked rapidly to engrave the die. The first stamps were printed on April 19, just one week before they were scheduled to be released to the public. They were rushed to post offices around the country, but only Hartford was given the honor of selling them on the first day of issue, April 26, 1935. All other post offices would have to wait until the next day. Hartford received 500,000 of the new stamps, but postal authorities feared that would not be enough and ordered more even before they were first put on sale.

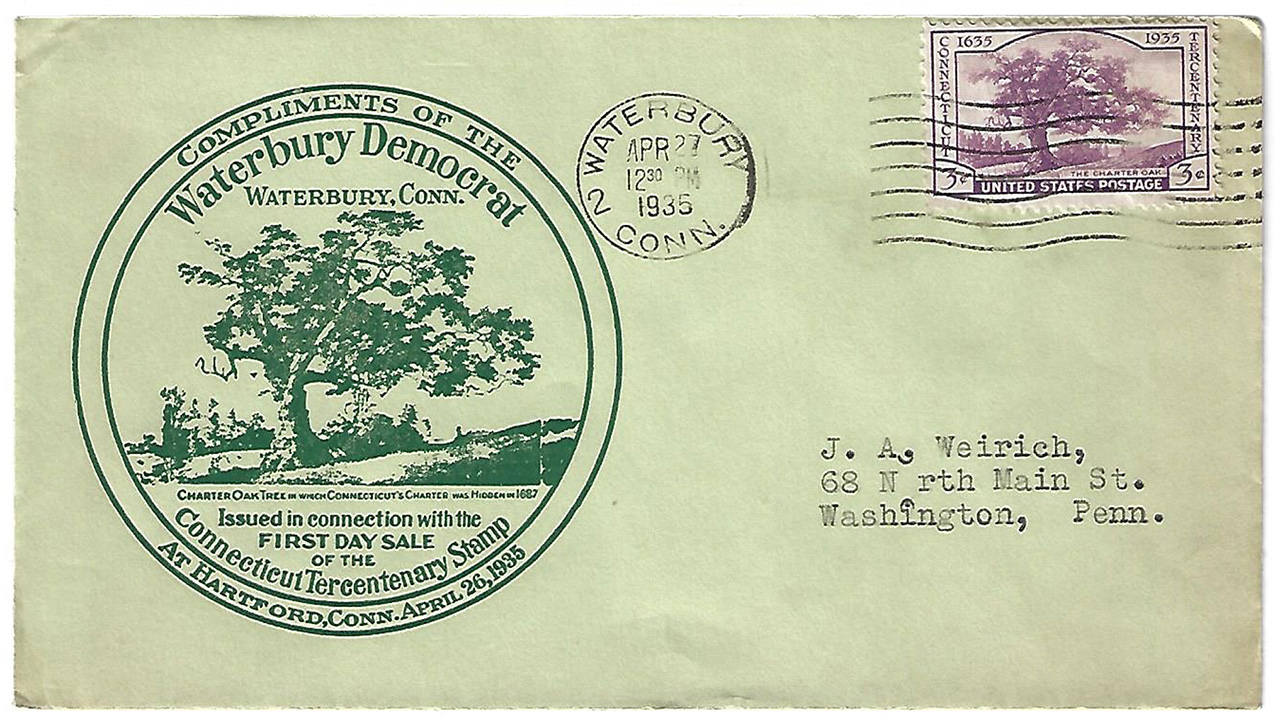

For the event, the Waterbury Democrat newspaper sponsored a first day cachet (that’s what philatelists call a special design printed on an envelope) that featured the Charter Oak. Readers who wished to receive a cover (an addressed envelope) with the cachet and first day of issue postmark could send in a request to the newspaper’s Stamp Editor. Because first day cancellations were available only from Hartford, the Democrat also offered covers canceled at the Waterbury post office on the second day. Requests poured in from philatelists across the country.

The cover shown above is one of the thousands prepared by the Democrat. It was printed in green ink on a buff-colored envelope, now somewhat discolored after nearly ninety years.

their patina polished

by passage of time

Throughout my life I have enjoyed unparalleled freedom, not only those rights the colonists attempted to preserve in the Charter Oak, but others they never conceived of. I’ve been able to choose my partner and spouse, my profession, my location and manner of living. I’ve been able to move and travel; to have or not have children, to limit the size of my family, and to expect that my children would have access to education. I’ve been able to vote without interference, whether military or psychological; to live without fearing that my home would be invaded by masked troops or that I would be arrested on trumped-up charges; to receive medical care, even in a rural community.

And more: I have been free to believe or to doubt, to accept or to question, to read and study and write.

I have long regarded these as more than freedoms – as rights granted by laws, by our Constitution, and not to be taken from me. But the Constitution is not a Charter written on parchment, something that can be preserved in a hollow tree. It is a concept enshrined in law that can be changed by law, and that is its strength… and its weakness.

The Charter Oak was felled by storm, but it is not only storms that can kill a tree.

strike down trees and laws alike –

a ruler’s right

The colonists knew that freedoms granted are not freedoms guaranteed. They can be as easily stripped away as leaves from a dead branch. Those who questioned the king’s might and right to rule absolutely were punished.

In my eighty years I have seen many threats to our freedoms, from foreign tyrants to governmental witch hunters, from nuclear tragedy to environmental disaster, from unchecked power to unbridled greed. Today, I fear I see them all gathered before me.

Where do we go from here? Do we as a people have the will to stand strong and free?

the old oak still buds

leaves of hope