In the spring of 2024, I taught a hybrid course, ENG 404: Special Topics in Creative Writing, at Parchman, the Mississippi State Penitentiary. My course, “The World We Have: Reading and Writing Creative Nonfiction,” was offered by the Prison to College Pipeline Program founded in 2014 by Dr. Patrick Alexander and Dr. Otis Pickett, and sponsored by the University of Mississippi; previous courses have been on Shakespeare, Mississippi writers, the civil rights movement, and the blues. Students who complete courses with a grade of C or better receive full credit from the University of Mississippi, and, though at this point few courses are offered, the goal is eventually to enable students to receive a degree.

Parchman is a maximum security prison, with about 2700 incarcerated men. It has a Death Row and various other Units ranging in levels of security. Founded in 1901, it covers 28 square miles in the Mississippi Delta, which is flatland with brutal summers and very few trees. It has a notorious history; formerly known as Parchman Farm, it was run on the plantation system with unpaid convict labor—essentially, slave labor—and it exemplified all the racial injustice and general cruelty of which humans have been capable. Though improvements have been made, living conditions still range from difficult to unimaginably atrocious. For instance, the building in which I taught was clean and airy, and had both heat and air conditioning—but the adjacent building in which my students lived (and which I was not allowed to enter) had something like four toilets for 80 men, and only recently got air conditioning, in summers that top 100 degrees. And this was the “nicest” of the Units. I asked my student Armon Randall what it was like, after he had been switched from Unit 25 to Unit 30 in order to teach in the new Warden’s educational program. He said, “Put it this way. From 25 to 30 is like from Beverly Hills to Compton. 102 guys. Open bay.”

I had team-taught at Parchman with Patrick Alexander twice before, about seven years ago, dividing class time between his focus on the literature of incarceration and freedom, and my focus on creative writing—but this semester turned out to be different. For one thing, though I had a teaching assistant, Kelsey Fox, who is getting her Ph.D. at the University of Mississippi, I was the sole instructor. For another, though I am not quite sure why, it was possible to learn a lot more about my students’ lives. In the past, I rarely knew what had sent these men to prison, or for how long, and I was told never to inquire.

Before the Spring 2024 semester began, about ten of us drove the seventy miles from Oxford to Parchman to introduce the program and ourselves. We sat in a semi-circle with the dozen or so interested students, in a large airy classroom in Unit 25—which used to house incarcerated men in pre-release, but now, though still the lowest security unit, houses men with all degrees of sentencing. After Patrick had introduced the university administrators who were attending, and Kelsey and me, he asked the men to introduce themselves. I’ll never forget what happened next. A large, powerful man with a booming voice came to the mic and said, “I’m Carlos. I’m in for life plus ten.” Others followed. “I’m Ledale. I’ve been here almost 30 years, since I was 17.” “I’m Jerry. I’m here for life without parole.” “I’m Joe. I’m 65. I’m here for life without parole.” Shaken and nearly crying, when I got to the mic again, I said, “This will not be an assignment and it’s separate from what you will be graded on, but I REALLY REALLY REALLY WANT YOU TO WRITE YOUR LIFE STORIES.”

And so they did.

Before I retired in 2022, I taught at the university level for nearly fifty years, but I never had a teaching experience more intensely meaningful, or one that gripped my heart and soul more, than this course at Parchman. I hated for the semester to come to an end; my students continue in my thoughts, and if I have another chance to teach for the Prison to College Pipeline, I’ll be there in a flash. I learned so much more than I taught—about suffering and hardship, guilt and remorse, yes—but also about dignity. I loved my students and was incredibly proud of what they learned and who they had become.

You will notice that many of these narratives are excerpted; that’s because, at the very end of the semester, we discovered they were forbidden to publish any mention of their crimes or of anything that had happened at Parchman. This was a blow, especially to several men who had written their way through hell, only to discover that parts of their narratives had to remain unshared. You’ll be able to tell who they are. And when I was not able to use someone’s narrative at all, since the whole narrative was about the crime, I’ve instead included one of that person’s poems written during the semester.

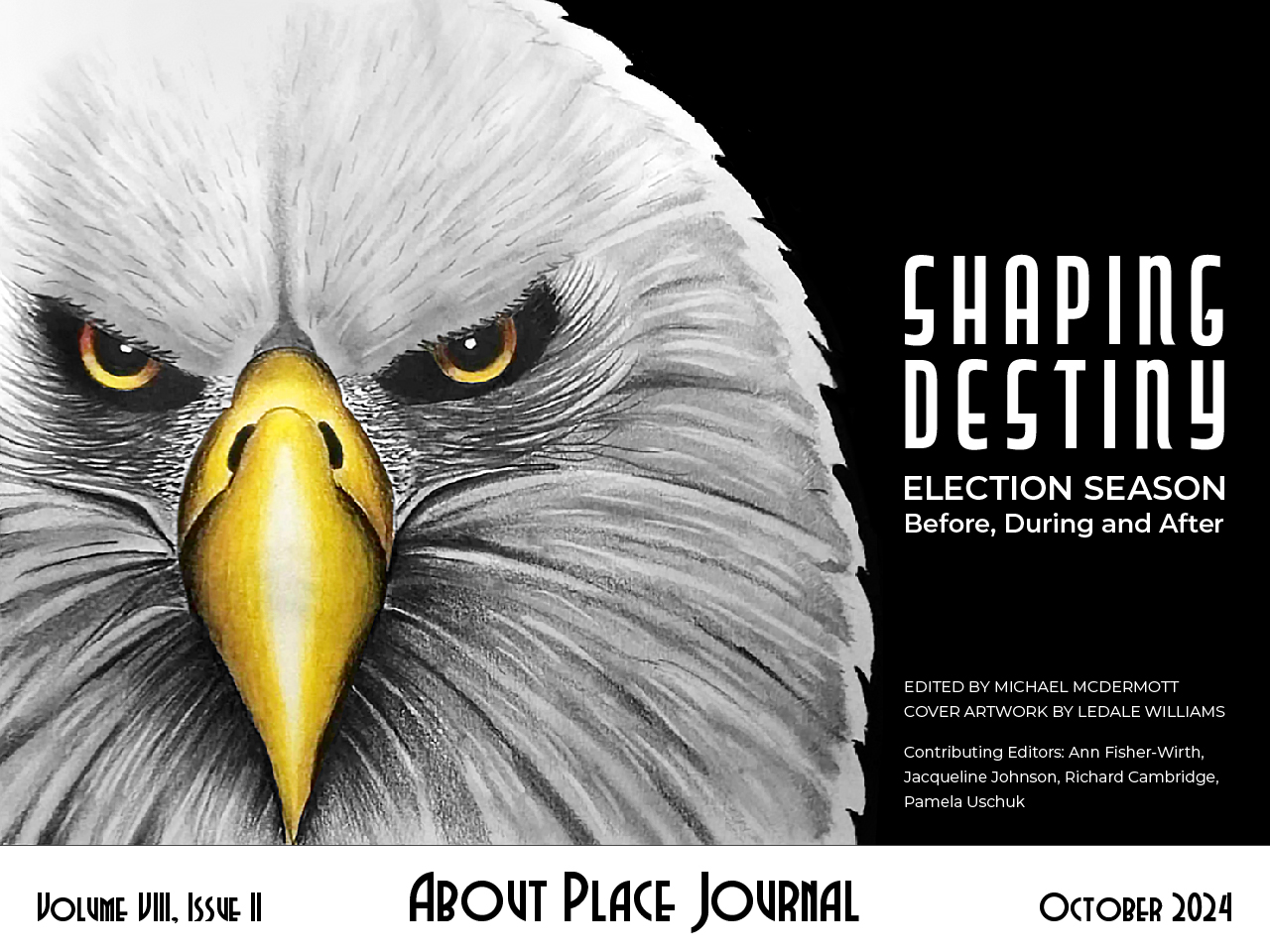

One of my students is also a gifted artist: “Eagle,” used for the journal’s cover, is part of his portfolio. Using only colored pencils, and with no art training, he created this beautiful image of strength and freedom.

I have written permission from each of these men to publish their work and their names. I am honored to present them to you.