To C.

Once on one of our many road trips between St Louis and the West, we pulled into a rest area off Highway I-70. It was bright, hot, and dry. The road was about to cut through the San Rafael Reef where jagged beige and pink sandstone cliffs tilt precipitously from the desert into the blue sky. The reef marks the exposed eastern edge of rock layers that fractured over deeper basement rock compressed upward from the orogenic mountain-building forces of plate tectonics. Perhaps because of the suggestion of an oceanic reef in the middle of the desert, I remembered this geologic form and the path through. 3.5 million cubic yards of rock excavated and 4.5 million dollars spent so that eight miles of road could be built through rock strata of the Jurassic era. Westward.

“The journey of the rock is never ended.” Lorine Niedecker, a poet of the upper Middle West once known as the North Central Region, began these lines in her journal while on vacation driving around Lake Superior with her husband Al. Their road trip took place in 1966, the same decade when I-70 was built and blasted through the San Rafael Swell: “In every tiny part of any living thing are materials that once were rock that turned to soil. […] Your teeth and bones were once coral.” Your teeth and bones were once coral, mollusc, foraminifera, bryozoa, shells, husks, precipitates of calcium carbonate. We mineralized from oceanic and interstellar dust. The catalysis and decay of many lives are in our bones and teeth and blood. We lingered at a rock outcropping overlooking distant canyons, breathed in the sun and particulate matter, then got back in the car.

Even before the highway was built, the area was prospected for uranium, and abandoned mines riddle the canyons. I forgot about this until I learned that St Louis, where we lived, had been the center of uranium processing during the Cold War and postwar boom. We foraged wild chives and nettles at the Weldon Springs conservation area before we knew it was the site of munitions manufacturing and uranium processing in the forties and fifties. Just north of where we had been, there is a mound of bare riprap rising seventy-five feet above the surrounding prairie. Beneath it is 1.48 million cubic yards of chemical and radiological waste encased in a containment cell. The cell is designed to last 1000 years; radioactive isotopes have half-lives of thousands upon thousands of years.

I imagine particles of an atom rotating out of orbit, the widening gyre of things falling apart. Radiant radioactive despair as a form of unmaking—ungathering.

You and I spent every other year apart: together in St Louis, then apart in St Louis and California, together in St Louis, then apart in St Louis and California, together in St Louis, and then finally no more apart. We said we would move west.

….

The first house we put an offer on in Portland was a 1970s two-story Craftsman on the top of a hill southeast of Multnomah Village, not close enough to walk there but close enough to still feel in the vicinity. You were ecstatic; I was glum. I had not seen the house yet, at least, not in person.

When I visited during the house inspection, I was recalcitrant and peevish. I missed home. I missed St Louis. Small petty details weighed on me as I wandered dejectedly through the house with our then 4-month-old in the carrier against my chest and our 2-year-old running excitedly up the stairs and playing with toys.

A few days later our house inspector emailed us the report for the radon test after it was completed. He was curt and professional: “The EPA recommends remediation action at radon measurements of 4.0 pCi/L and above. The results from this 2-day test of 3.2 pCi/L fall below that level. Remediation is not recommended for this property at this time.” When we opened the attached radon reading, we found readings for every hour over a 48-hour span. The measurements scattered up and down from as low as 1.1 to as high as 5.7. There was no discernible pattern. Later you called him to ask what this meant.

Radon is a radioactive gas emitted by uranium as it decays. Elevated radon levels in Portland correspond to soils with coarse-grained granitic gravel, granite which contains uranium, granite which traveled to Oregon during the end of the Pleistocene ice age around 15,000 years ago when water from Lake Missoula periodically broke through its glacial dam and recurrently flooded across a thousand miles, overflowing the Columbia River Gorge and forming a lake in the Willamette Valley. Radon occurs naturally in soils everywhere; it is odorless, colorless, and “inert,” and is the second leading cause of lung cancer after cigarette smoking. If a house sits on soil emitting radon gas, its downward pressure on the earth tends to draw up the gases inwards and upwards through cracks and seams in the house. A radon test measures picocuries per liter, that is, the amount of radioactive decay equivalent to a trillionth of a Curie, the radioactive unit named after Marie Sklodowska Curie who studied radioactivity and eventually died from it.

On the phone our house inspector explained that although the EPA sets 4.0 pCi/L as the threshold for remediation, there was no “safe” level of radon. He shared that in his own house he had sealed the crawlspace under the house with the thickest sheeting available. His wife had passed away from cancer and he was a single father with three young children. He didn’t tell us this but our real estate agent did. Marie Curie had two daughters, Irene in September 1897 and Eve in December 1904, who she raised as a single mother after Pierre Curie died in a road accident. Irene was 7 years old and Eve 17 months old when their father died; they were 36 and 29 when their mother died.

….

At the Weldon Springs containment site in St Louis, the white-grey mound surges up with a single staircase to climb to its plateau. Nothing grows in the riprap though the site is surrounded by restored grasses. About 50 miles east just across the Mississippi River, another mound almost 100 feet high eerily mirrors it but rises softly green with grass. This is the tallest mound of Cahokia, a pre-Columbian city once made up of hundreds of mounds, buildings, and agricultural fields at its height in the 11th and 12th centuries. When I noticed this correspondence, I drew you a card with an illustration of the two mounds with their twin staircases like a stereograph photo and mailed it to you where you were living in California at the time. In a malaise, I was convinced that air pollution and radiation were slowly seeping through my lungs, my body, my bones. Months before, news of a fire seething underground in a landfill right next to another nuclear waste site near the St Louis airport had made national headlines. At the university where I taught, I read with my students DeLillo’s White Noise and St Louis-Post Dispatch newspaper articles from the 80s on the “LEGACY OF THE BOMB” and “ST LOUIS’ NUCLEAR WASTE.” I had found pdfs for the old Dispatch articles on the website of a local community group called “Just Moms” advocating for the EPA to clean up the airport landfill.

I felt immobilized and vaguely unsettled. We saw each other twice a month for long weekends and on holidays. You flew to St Louis once a month and I flew to Oakland once a month. I charted my period on a fertility app and we looked for the highlighted predicted ovulation days to decide when to buy plane tickets. You started applying for postdoctoral fellowships and academic jobs everywhere you could and all of them were far away from St Louis. I bought a supply of pregnancy tests. I began reading a book about natural birth. You flew to St Louis and I flew to Oakland.

Sometimes I am not even sure I lived in St Louis even though I still dream upon it as a half-thought upon a half-life.

….

She studied Asian American literature and became a professor at a prestigious university. End of story.

She was a star cellist, went to Harvard and Juilliard, decided against a music career and instead went to medical school and became a doctor. End of story.

She was a lawyer that worked on intellectual property rights and immigration law while also publishing poetry on the side. Then she quit her day job, became a full-time poet, and got a new job teaching poetry at a prestigious university. End of story.

She became a famous architect, no, sculptor, no, environmentalist, and had two children. End of story.

She never had children. End of story.

Doppelgangers are a trope in Asian American literature. Sau-ling Cynthia Wong writes, “By projecting undesirable Asianness outward onto a double…one renders alien what is, in fact, literally inalienable, thereby disowning and distancing it.” What is desirable or undesirable? Sometimes it is hard to tell the difference. Sometimes it is the desire that is hard and opaque and mute. Somewhere in these stories there is a story of me, or rather, a story of what I wanted to be or not be, a story of expectations not my own, of misdirections, of meanders. She is not me; I am not her.

….

I had seen the 1944 meander map of the Mississippi River somewhere before. Even before I began showing a plate from the meander map to my students in St Louis, I had been enthralled by the thick sinuous ropes of color showing the historical courses of the Mississippi twisting across the riparian topography. Spread over multiple plates, the map shows how the river has shifted in undulations across its alluvial plain from Missouri to Louisiana. I had no real sense of the scope of time represented by the map; it was the environmental and aesthetic texture of the river that held my eye. The weaving of tinted temporalities reminded me of the way memory surfaces and synchronously haunts the present, the way it bends and gathers our senses so that some things never go away. But perhaps I have misunderstood the meander map.

The cartographer of the map did not study rivers; he studied rocks. In 1931, Harold Fisk moved to the Midwest from Oregon to pursue his doctorate in geology. In 1935, he married Emma Ayrs, a fellow geologist from Tennessee whose name reminds me of Jane Eyre, and they moved to Louisiana where he began teaching at the state university and would eventually use geological research to create the meander map of the Mississippi River. The map stretches over multiple plates and shows stages of the river over the course thousands of years with data going back to the end of the Pleistocene which, during Fisk’s lifetime, bordered the beginning of our current geological epoch.

Fisk’s doctoral research had been on the basalts of Oregon—he analyzed and described the chemical composition of the Columbia River flood basalts so that each flow could be distinguished from the other. Today, geologists can still use the data from his reports to trace the provenance of basalt rocks. With the same meticulous and comprehensive approach that he used to study flood basalts, Fisk parsed and charted the geological history of the Mississippi River. At such a scale, the riverbelt appears continuous from a certain moment about a thousand years BCE onward as the land around it shifts and water flows to accommodate its pitches and climes. If you are a geologist like Fisk, you see how the rock moves and then how everything else moves around it.

….

Stretch

swell

billow

And

Heaved

The constellations

stoop down

and

bend

Among grass

Burn

or rise

In

Answer

Heaped

Forms

Glittering

Nourished

days with

twilight wooed

language and

Gave

the earth

All

being

blooming wild

quick with

murmurings

soon

soft

solemn

low

Over at once

am wilderness

….

Sometimes I imagine that it began when our first child was born; other times I think it was when I felt I had to pursue a career and be a mother and figure out how to bring my baby to lectures and conferences and fellowships, or it was when you felt you had to pursue a career and be a father and pave a way to another place for us to be together. You went west and I hesitated. You came back and we decided, no more apart. But why is it that I cannot stop tracking how far apart we stretched and contracted? Why is it that I keep asking what led us this far?

Did it begin in St Louis when I was there and you were not? In St Louis where Michael Brown was shot and killed in the suburbs, where they refined uranium during the Cold War era, where Lewis and Clark began their expedition when some people believed there was a frontier and beyond that the wilderness. Where the mounds of Cahokia rise up, soft green mounds across the river from downtown, reminding us of another era, another people, another city, pre- and post-Columbian, their decline, and their apocalypse, whatever it was.

Or is it our own restlessness? Our desire to err rather than to settle? Our retracing and refusal of that westward forward narrative?

When we visited Cahokia, I was surprised by how small and unassuming the mounds were. I had envisioned the Mesoamerican pyramids I had visited in Mexico. These green hills were modest, almost no longer even bearing the gesture of human shaping. We walked on mild trails surrounded by grasses, up simple stairs, to the windblown platform top. Sat on the curved edge buffeted by wind’s torrent and sound, looked across to the city skyline, the arch and pillars of skyscrapers rising up from a cloud of trees. From this distance, our gestures, even those that are extravagant and incisive, are reduced by contemplation.

What is often seen is that there is a husband a wife a child a dog; but often there is no husband no wife no child no dog. Or there is less while there is also more—less husbands less wives less children less animals less things while there are also more fathers more mothers more children more animals more plants more everything. We believe, without questioning it, that this is a family, that a child needs a caregiver, and that the caregiver must feed and clothe and shelter and care for the child. What do we not see? Even though we understand mothers fathers children and so forth to play different roles, and even though we understand many relationships as not reciprocal or shared, but as necessarily all-consuming, though a child cannot care for, say, a mother in the same way, though a mother gives and gives and gives, we assume that something called love makes this alright. But is it?

At some point, I began to feel the gaps between who I was and what I thought I should be. At some point, I sensed that the gaps were not between myself and something else but also within myself. Perhaps it began earlier, in the moment that I stepped out of my home and into a place that was not my home, a place called academia, a place where a woman once claimed, “I didn’t realize I was Chinese.” Or even earlier, when my mother stepped out of her home and into a school where she would teach and then leave to get married and move from Taiwan to California. Maybe it began because all these things could happen to a woman: she could become a mother, she could get married, she could have a spouse who needed to work long distance, she could be talked to in a certain way, she could be expected to talk in a certain way, she could be expected to give birth, she could be expected to labor, and to work, and she could be expected to come back to work three months after giving birth, she could be a professional, she could be a professor, she could be everything but a woman, she could be nothing except a woman, she could claim to be Chinese, she could claim to not be Chinese. Could these things be considered a rift or a subduction? Is it all in how one meets it and how it affects one’s sense of self and the world? Or is it in the organization of the world, the order of things?

How to think like a soft green hill? Greenly mounding. Bowing down to the weight of the earth. Earthing the Moon and the Sun. Spasming the stars.

….

These days I cannot remember names of places or people in St Louis that were once so familiar to me a year ago or even a month ago or a week ago. I cannot place where the fountain in Tower Grove Park was nor where Crevecoeur cut across Grand Ave. I cannot find where we keep the spare lamps and lamp shades and the Scrabble game even though I know exactly where we kept it in our house on Botanical Ave—in the closet in the sunroom, on the bottom left-hand side. When our children complain or whine or ask nonsensically for something over and over, when you say something that twists inside me, I snap too quickly. I am angry; I am angry at them, I am angry at you, I am angry at myself. I am angry with how society has organized itself, I am angry with what it means to be a woman in a time when Roe v Wade has been overturned, I am angry with what it means to be a woman since before that time, I am angry that it is impossible to be a full-time mother with a full-time career or even a part-time mother with a part-time career. Intuitively I understand that the person I am after having children is completely different from the person I was before having children. I imagine a neurological fabric rent with volcanoes and magmatic vents. I imagine crackling explosions, hisses, and rumbles, endless smoke and haze, but all I see is rain and clouds and the grey green of our neighborhood. Something or someone can be destroyed in this landscape.

Volcanologists Katia and Maurice Krafft died in a pyroclastic flow of hot gas and ashes while studying the eruption of Mount Unzen in Japan in 1991. They began their careers traveling the world to study, document, and film these beasts “disemboweling themselves,” and to educate the public on how to monitor and respond to volcanic eruptions. They fell in love with each other and volcanoes and eschewed family life with children. They were often playful, capturing each other on film donning silvery astronaut suits and nonchalantly sauntering near bright red and orange lava flows; they made silly faces and gestural jokes and delighted in their dangerous proximity with volcanic debris shooting through the air, toxic gases, and slow coursing lava. Something or someone can be in love.

I cannot remember and yet all I want to do is track back and figure out, where, when, did it begin? Why did I? Why did you? How did we? End? Here?

….

In Oregon, the hills are forested with tall trees and the rock a dark gray basalt run over and cut through with water. Our first fall there, we tried to go on hikes and often found ourselves mired in rain. Clouds, dark green shadows, drizzle. Beacon Rock was closed, too slippery and dangerous to climb up, so we wandered to another trail nearby and gazed at the Columbia River. Mount Tabor we visited frequently, the children climbing and jumping on the long steep stairways up to the reservoirs. The pools were ornately surrounded by concrete walls and wrought iron and guarded by miniature crenellated fortresses bounded by trees with a view of the city and walking paths that we eventually circled over and over over the course of many visits. Powell Butte we also frequented to hike up its forested western side onto the exposed grassy hilltop. Once we had a glorious morning there, taking a nap in a spot of sunshine and then tottering down for brunch. We never remembered to bring rain gear so we tramped around in damp clothes and muddy hiking boots among ferns and Douglas firs, our son in the baby carrier flecked with rain dew and our daughter splashing from puddle to puddle.

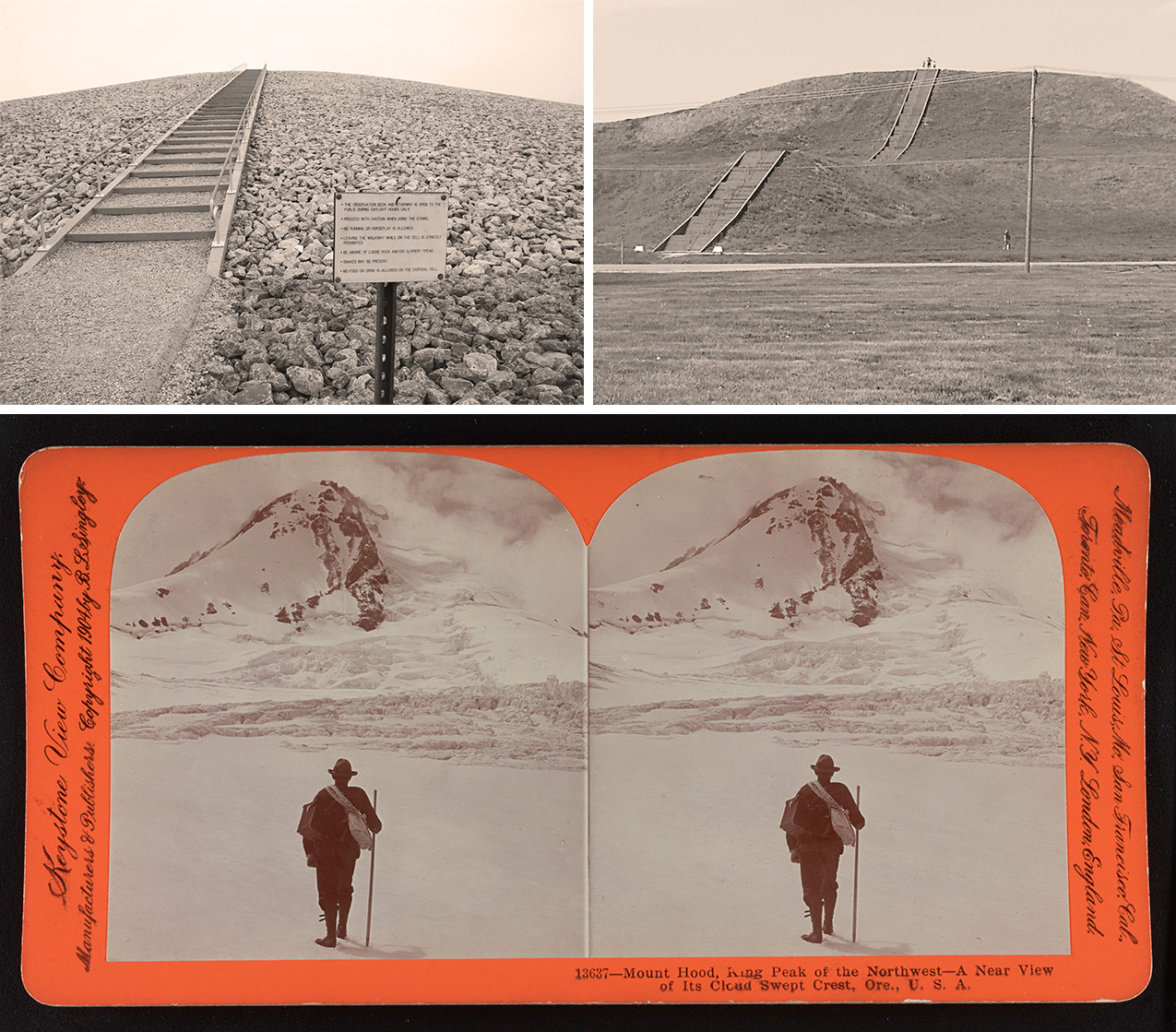

That spring, we trekked to waterfalls where our daughter, enamored with the water, pulled you into the icy streams with her. A cold green damp hugged the hills and mountains and made everything feel tropical and prehistoric except that it was terribly cold and wet. Like Mt Hood, which looms as a distant snow-capped ghost when the sky is clear, these smaller hills and mounts are the remnants of volcanic activity. Beacon Rock, Mount Tabor, and Powell Butte are the carapaces and fossils of lava flows from vents that spanned a region of Oregon from the northern Willamette Valley southwest to Washington only 2 or more million years ago.

Beneath the green and the gray is a deeply fractured landscape slowly slowly so slowly being reborn again and again, sedimenting, metamorphizing, magmatizing, again.

….

The Prairies 2

These swells rolls fluctuates Who poised played crisped fanned heaved smoothed planted And hedged whose bends sweeps seems tramples once stir burn rise Answer Was hewing rearing glittering These Nourished fed bowed murmured blushed wooed Gave came vanished settled The prairie Hunts Yawns mines All All builded heaped yielded Welcomed forgot Thus change Thus arise And perish breath Fills builds issues Roams here here Bounds Fills hides Blends sweeps breaks

….

Where Fisk had moved from Medford, Oregon—a sundown town—to the Midwest, married, and had a family; we had married, started a family, and moved from the Midwest to Oregon. His professional interests, one might say, were purely geological. Mine are not. I cannot think about rock without thinking about immigrants and errata. I cannot think about tectonic plates and subduction and rift without thinking of all the women who have tried to have a career while being a wife, a lover, or a mother. Basalt flows across and then dips deep into underground magmatic chambers only to explode again. Coral and sea lilies disintegrate into calcareous materials that sift into the ocean, the earth, to become the teeth of another creature.

….

I thought I would write about a westward move that revised the Lewis and Clark trail from Missouri to Oregon but instead everything is imperceptible yet measurable. There are numerous wests here. Because I have braided my fate with yours, “There are things / We live among” (Oppen, for you). Our daughter is 4 years old. Our son is 2 years old. You and I have been together many years now. What have I been doing? Drawing landscape plans for our backyard. Sorting rocks. Transplanting rhododendrons and salvias. She said she would buy the flowers herself. Scattering. Sifting. Throwing together meals. Picking blueberries. Picking huckleberries. Subducting. Or rifting. While our children grow older. While we grow old.

Our separations are multiple and they crease like fine wrinkles across the face of our time together-apart.

Notes:

“The Prairies,” original text by William Cullen Bryant.

“I didn’t realize I was Chinese.” Maya Lin, in “Between Art and Architecture: The Memory Works of Maya Lin,” Museum (July/August 2008), https://web.archive.org/web/20080915223311/https://www.aam-us.org/pubs/mn/mayalin.cfm.

“disemboweling themselves,” Katia and Maurice Krafft, Volcanoes: Earth’s Awakening, 1979.

“Imperceptibly, yet measurably,” a phrase somewhere in a book on Oregon geology.

She said she would buy the flowers herself. Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse.