Impossible… to happen

…human, but to pray for a share

… and for myself

Sappho, from Fragment 16

1. In October 2017 I became a mariner. I set sail from Longyearbyen, Svalbard, ten degrees from the North Pole. On board the Antigua, I wouldn’t have access to the internet. I wouldn’t see my cousin’s video comparing Democrats to Hitler. I wouldn’t see my great aunt’s meme likening Republicans to Hitler. I wouldn’t glimpse my mother’s support of Franklin Graham or my colleague’s mockery of Graham. On the Antigua, I could escape my growing anxiety over the great cracks in my relationships since the 2016 U.S. election.

The Antigua is a traditionally-rigged barquentine tall ship like those of the seventeenth century but with modern amenities like a gourmet kitchen and a diesel engine. I was joined by twenty-eight other artists from around the world. Besides the U.S., there were people from Singapore, Latvia, New Zealand, Australia, Taiwan, Canada, and England. We traveled north from the rainbow-colored glacier of Ymerbukta to strangely flat island of Moffen, farther and farther from the divisive noise south of the Arctic Ice Cap. We helped the crew raise and lower sails, splashed ashore in rubber zodiacs, and hiked desolate tundra to work on our art. One artist wrapped batik cloth around icebergs granting them personhood in a Buddhist-like ceremony. Another recorded calving glaciers with an underwater mic. Another shot an experimental film featuring plastic inflatables, garish and grim against the silent whiteness. Another sculpted glass replicas of small ice chunks. Another made love to glaciers. “This trip has an enormous carbon footprint,” she said, “so we have to take responsibility for it, and I want love to be the means by which I do that.”[1]

I had come to write a series of fragments to reflect the fracturing Arctic, the ice that creaked, moaned, calved, split, and melted. But once we set sail, I realized that though I admired fragments as a literary form—my favorite poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, is master of the fragment—they were impossible to write while living with the other artists in the close proximity of the ship. Even on shore we were relegated to a bordered area guarded by three formidable women carrying shotguns to protect us from polar bear attacks. A wonderful cohesion developed as we slept, ate, and worked elbow to elbow.

2. I’d brought along a copy of Coleridge’s 1802 The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, a poem I teach every year. Before squeezing into bed at night, I reread the familiar story, how the mariner shoots an albatross, how the crew hangs the slaughtered bird around his neck for penance, how in the land of mist and snow, there is no redemption, only a dying world. The wind stops blowing. The sun sits like a disc on the rim of the earth. The ship stagnates in its own shadow. Rain ceases and the ocean begins to rot. As the crew members drop dead and resurrect as ghosts, the mariner sinks into existential depression.

Coleridge did not travel to the north or south poles, but he took some of his images from early Arctic travel narratives. In the wee hours of mornings—the only time I was alone during the voyage—I stood on deck among the ropes and pulleys imagining myself as one of those seventeenth-century mariners who might bring home alarming stories of a world gone awry. During the days, I strolled around with my notebook watching the other artists.

One afternoon, I was standing in front of Esmarkbreen, a glacier on Svalbard’s west coast. Out of the corner of my eye, I spotted a woman, gray hair flying in the wind, thick black glasses, and an open face, who, like me, was one of only several middle-aged people on board. Annique was collecting water in jars and tubs. She looked up as I walked over. “I’m fascinated by water in all its forms, by how water connects us,” she said in a melodic Australian accent, which immediately drew me in. “The water that we find here in the Arctic is the same water that travels around the world. It’s the same water that runs through our bodies. Water doesn’t have a notion of borders like we do.”

I followed Annique to the top of the glacier where she rolled out sheets of mulberry paper two or three meters long. She asked me and several other artists to cover our hands with graphite powder and then place our hands on the paper. The warmth of our skin melted the ice below, mixing with the graphite, so that our human touch became marks embedded on the paper. The idea, Annique said, was for us to draw in partnership with the glacier. As I pressed my hands on the paper, I felt intimately connected to the ice and my comrades.

3. When I struggled to write fragments in the Arctic, I don’t know why I didn’t link my predicament to the day-to-day fragmentation I’d experienced since the U.S. election. At the university where I work, more students than ever lined up for counseling services, mirroring national trends. People who’d worked together for years building successful student programs stopped speaking. I stopped speaking to a woman who, all evidence to the contrary, accused a friend of racism. When my parents called with Fox News blasting in the background, I froze and delivered short yes and no answers. My husband’s bitter argument with one of his best friends in a Chicago restaurant was a reminder of how easily relationships could crumble in this brave new era. I hated the division. There’s nothing worse than the ache of not connecting with the people in my life, nothing more devastating than being at the center of a shattering community. Cutting off colleagues, friends, family, and being cut off by them, made me feel as if there was something terribly wrong with me.

4. One morning on the Antigua, we anchored on the northern tip of Svalbard in a bay. Huge snowy mountains punched through the sky. We went ashore on the island of Amsterdamoya, high waves besetting our zodiacs. Kristin, one of our polar bear guards, a dark-haired Norwegian in skin pants and jacket she’d sewn herself from seals she’d hunted, guided us to the settlement of Smeerenberg—literally, blubber town—the best-known whaling station of the seventeenth century. At first, no one noticed the settlement because at the south end of the island was a huddle of groaning walrus. Our entire artist troupe tiptoed over to watch the barking Goliaths. They lifted their heads, yellow tusks razoring the sky. They belched and farted and rolled on top of one another. In a moment of recognition, we laughed into our gloves.

After half an hour, most of the artists strode away to collect garbage that had washed up on the beaches; a few lingered to film the walrus. The walrus were charming, and I too wanted to stay and watch them, but I felt drawn to the remains of the settlement, which I noticed was littered with whale vertebrae hundreds of years old. The bones were bleached white by the sun and wrapped in kelp. I walked among the bones and crumbling rings of red bricks—fragments of the blubber ovens once used to render oil from whales. The ovens cast eerie shadows across the sand pocked with dry snow. Whales, I learned from the books I’d brought, were slaughtered in such great numbers in 1640 that they virtually disappeared from Svalbard. The settlement was the first instance of oil extraction, the forbear of the modern petroleum industry.

I wandered down to the shore. One of the other guards was looking out to sea, shotgun slung easily over her shoulder. She squatted and grabbed a wad of kelp, which was strewn along the beach in a gilded band. “You can dry this and use it as parchment,” she said. I scowled at the wiggly mass spilling over her gloved hand, recalling the algae and bull kelp of my childhood on Mukilteo beach near Seattle, where my mother often took my brothers and me to play among the tide pools. I had been repulsed by the slimy organisms, long and curly like intestines or globular and organ-like, a heart or lung, and had turned away. But at Smeerenberg, touching the cold, slick life forms felt like the most natural thing in the world. These simple beings thrive by clumping together, the guard said, because they function as a group rather than as individuals. A weakness of humans is their complexity, I thought, and I felt a momentary longing for the impossible, to be as communal as kelp.

5. By the time I joined the Antigua, I’d already made friends with marine algae, of which kelp is one example. Months earlier, I visited the southern English seaport of Watchet, the setting of the Rime of the Ancient Mariner. I climbed to St. Decuman’s church, a squat stone structure on the hill above Watchet, where the poet first looked down on the seaside and imagined the mariner who is cursed to retell his story of shooting the albatross. I ate dinner at the Bell Inn, a traditional pub where Coleridge wrote the poem.

I’ve been fascinated with the Ancient Mariner for years. I’ve written scholarly pieces about how the mariner’s journey could be an indictment of Europe’s destructive practices, from global trade and scientific exploitation to the annexation of India, the horrors of forced labor, slavery, industrial capitalism, and environmental devastation. But one part of the poem has always puzzled me: the “thousand thousand slimy things,” prolific, alive, thickening the ocean and repulsing the mariner. The slimy things emerge throughout the poem, but the fact that they appear at the miraculous turning point has always seemed important. The mariner’s world is on the brink of apocalypse when he suddenly and inexplicably feels intense love for the slimy things. He cries:

A spring of love gushed from my heart,

And I blessed them unaware:

And I blessed them unaware.

At this moment of unconscious blessing, his curse lifts and the albatross falls from his neck.

What, I’ve often wondered, are slimy things? Sea animals? Primordial goo? Environmental waste? Or—as I was beginning to think as I walked the beaches of Watchet—kelp. The kelp and marine algae under my own feet on the Watchet beach was thick and various, as they would have been in Coleridge’s day. Kelp, I learned, was Watchet’s main export in 1797, when Coleridge wrote the poem. The Watchet kelp felt like a partial answer to a question I’d lived with for a long time. I couldn’t help but stoop to touch them, and soon I found myself shoving the organisms into my pack. Back at my hotel, I rinsed them in the bathtub to remove the oily, fishy scent, dried them in the window, and took them home.

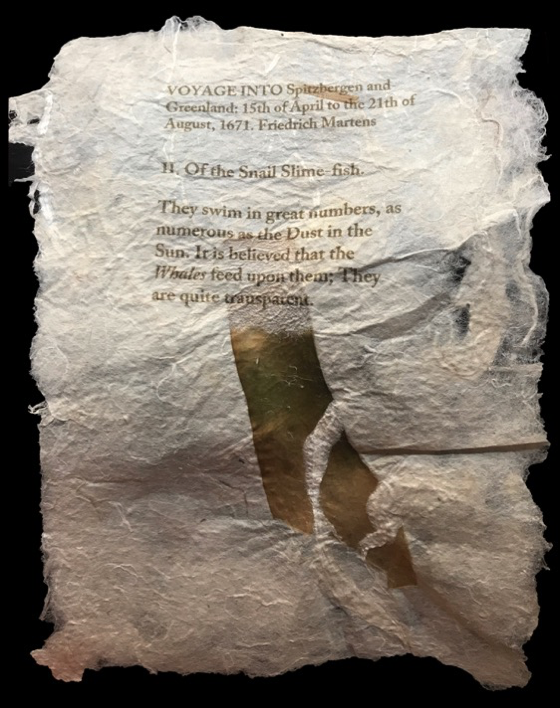

6. Besides the Ancient Mariner, I’d carried on board the Antigua a few Arctic travel narratives. One was the quirky seventeenth-century Voyage to Spitzbergen, Svalbard’s previous name, by Frederick Martens. Martens’ book is known for its savage account of whaling on Smeerenberg. He indulges in the goriest of details: “the Harpooner doth dart the Harpoon just behind the Spout-hole of the Whale … for that maketh him spout Blood sooner than if wounded in any other place … The first Whale we caught spouted Blood in such a quantity, that the Sea was tinged by it where-ever he swam.”

Coleridge, I knew, had borrowed liberally from the Svalbard traveler when writing the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, especially Martens’ characterization of slimy sea life. They’re shaped like caps, like hats, like buttons, like roses, like fountains, like spiders that dance on the surface of the water. Some have hair, some legs, some are amorphous, some are bluegreen, some gold-vermillion, some transparent. They are, writes Martens, “as numerous in the North Sea as Atomes in the Air.”

Standing on the edge of the North Sea myself, I realized that Coleridge’s mariner is revolted by the slime, but that revulsion is his path to redemption. The moment when he most despises the slimy creatures is the very moment he blesses them from the egoless part of himself. As a poet of the sublime, Coleridge was used to exploring that fragile border where individual identities break down, where the line between human and human, and human and environment, shatters.

Suddenly I was folding handfuls of the Smeerenberg kelp into my pockets just as I had the Watchet kelp. I brought them on board the Antigua, and dried them under my mattress—I had a very tolerant roommate. Kelp was the only item we could remove from the island other than garbage, as if kelp were a waste product instead of our future. Because the fact is, marine algae was part of the primordial goo responsible for creating Earth’s atmosphere billions of years ago. Today, it provides up to 80% of our oxygen. The idea I’d had as a child, of kelp as an organ, was right. The organism transforms the ocean into a liquid lung, an intimate partner, breathing our CO2 as we breathe its oxygen. Coleridge may not have known the science behind kelp, but he was in touch with its poetic potential.

7. My father, a retired plumber, and I have never agreed about politics, but we’ve traveled the country together on backpacking and hiking excursions, where we openly debate current affairs. I love our discussions, when we eventually stop spouting lines from media outlets, when we abandon public language for something beyond language. Once, on a trip to Utah’s Bear’s Ears National Monument, we had a sharp conversation that swung from public land to the welfare system. “I wish I could stay home and let the government take care of me!” my father said emphatically, as if he lacked compassion for those less fortunate while I argued that giving to the poor was our duty. We stopped at a gas station. An old man wandered up in tattered clothes asking for money. I remember, with some shame, how I left my window rolled up while I watched my father pull out his wallet and place two fifties in the man’s hand. But after the election, those discussions with my father crumbled. Meaning, we don’t debate anymore. I can’t speak for him, but I know I’m afraid to bring up politics, afraid our rigid opinions will splinter our bond. And yet, we have lost something in not being able to talk through disagreements as we used to. Of all the fragmented personal connections since the election, this one bothers me most.

8. One night the Antigua was pitching wildly from side to side; many of my comrades were in bed seasick. I stepped outside my cabin into the small hallway to find Annique leaning against the wall talking to two artists from Taiwan. “I use the aleatoric method,” she said, her thick salt and pepper braid draping over her shoulder, “where some vital part of the work is left to chance. For me, chance is the materials themselves. I allow the materials to do what they want, what they must. I have the agency initially, and then I step back into a partnership with the materials. And that’s how we should be with our planet, working with natural processes rather than controlling and dominating them.”

She kneeled among her materials: a small hand blender, paper pulp in an old cottage cheese carton—she’d made the pulp from discarded cotton t-shirts in Australia—a few yellow felt couching sheets, and a bottle filled with slimy green water.

I asked about the green water.

“I cut kelp up into small pieces and blended it,” she said with a kind of glee in her voice. “I’m not sure what it will do!”

I’d begun to feel unwell in the tossing ship, so I stumbled back to my cabin. I fell in and out of sleep all night, images of green slime and paper pulp mixed with memories of the first time I made paper. My mother often brought crafts to our Mukilteo beach trips, supplies to fashion tie-dye shirts, wax and plaster of paris to craft sculptures of our hands in the sand, and recycled newsprint to make handmade paper. I remembered the magic of lifting the sheet from the slurry, the primordial goo from which paper is made. Form from formlessness: it seemed like creation itself. That delirious night turned out to be a premonition because later, back home in Chicago, inspired by Annique, I would immerse myself again in the analog art form of hand papermaking, using the kelp I had collected from Svalbard and Watchet. I would add it to the slurry, embedding fragments of the parchment-like organisms into the wet sheets and employ kelp as formation aid to bond the fibers, as if I could hold everything together with slime.

9. Literary fragments, I’ve come to realize, are like kelp. They are not lone individuals but vitally connected to what’s around them. A piece of writing in fragments can be held together by repeated images and phrases. Characters. Humor. The development of an idea. Fragments are communal in the best way. They demand accountability: readers become the connective tissue, making leaps and filling in gaps. When I learned that the literary fragment dates back to the Greek poet Sappho, around 620 A.D., and that her poems were fragments only by accident—waste products, some were found in an Egyptian garbage dump, others on the papyri used to wrap mummified bodies—I thought of the whale bones wrapped in kelp on the shore of Smeerenberg, how so much meaning can be found in rubbish.

10. After two weeks at sea, the Antigua docked at Longyearbyen. Within the grasp of the internet, our cellphone and computer screens lit up with the first news about Harvey Weinstein and reports of Russian trolls using social media to sow divisions among Americans. I could not have felt less divided from m fellow human beings. But then, outside the confines of the ship, our group dynamic changed. We were twenty-nine individual artists again. We didn’t eat every meal together. We weren’t a whisper away from a conversation. I experienced this separation as a loss, even as I knew it was inevitable.

But what I can’t forget is how, the day before we departed the high Arctic, one of the filmmakers said he wanted to record us reenacting the walrus community of Smeerenberg. I can still see us on shore, rolled on top of one another, breathing together, lifting our heads in unison like the gentle giants.

_________

[1] Devra Freelander, to whom this essay is dedicated, was one of the most generous and insightful artists on board. Her life was taken on July 1, 2019, while cycling in Brooklyn New York. She is greatly missed.