Clifton, SC

John Lane, writer and old friend, and I are having breakfast at Dolline’s, a diner in Clifton—scrambled eggs, patty sausage (with the ubiquitous spatula hole in the middle to check for doneness), silky smooth grits dripping with butter, and Folgers flowing when your cup is half empty. On Wednesday mornings, a group of folks in their 60s, 70s, 80s, and maybe one or two in their 90s, get together to sing hymns and old traditional Christian songs. The guitars, mandolins, and the errant banjo aren’t expertly played, and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir has nothing to worry about with this group. Some folks seem to have invented their own key for singing, and a tremolo soprano in the corner leaning on her tennis ball-tread walker reminds me of my own mother’s consistently sharp choir vocals. Few things, though, better capture human connection than singing hymns with the right group of people. It is the music of my childhood, having grown up in a Fundamental Independent Baptist Church, and I am plunged by these songs into reverence and fellowship from those Sunday mornings in my infancy when my mom would hold me in her arms during “invitation.” “Old Rugged Cross,” “Softly and Tenderly,” and “Have Thine Own Way, Lord!” are as etched into me as any genetic code my parents might have passed on.

The good folks at Dolline’s sing some of the old hymns I know and a few gospel songs we’d only sing outside of church, such as Ferlin Husky’s “Wings of a Dove” or “I Saw the Light,” because as my pastor used to say, “Hank Williams was a little too earthy in his ways to be letting his music into a house of worship.” The only records we had in the house until the mid-1970s were collections of hymns, Johnny Horton’s Greatest Hits, Marty Robbins’ Gunfighter Ballads, Tex Ritter’s Hillbilly Heaven, and something by Johnny Cash we weren’t allowed to play. My dad used to say this selection is the only real music out there.

After a few more songs, John says we need to go and see if the weather will hold for short river trip. I agree, pay my check, thank Dolline, nod to the singers for letting me share, and hum a few old melodies all the way to John’s truck. John invited me here spend some time with his wife Betsy and him, dig in to some memories of my five years in Spartanburg, and paddle a stretch of the Pacolet River.

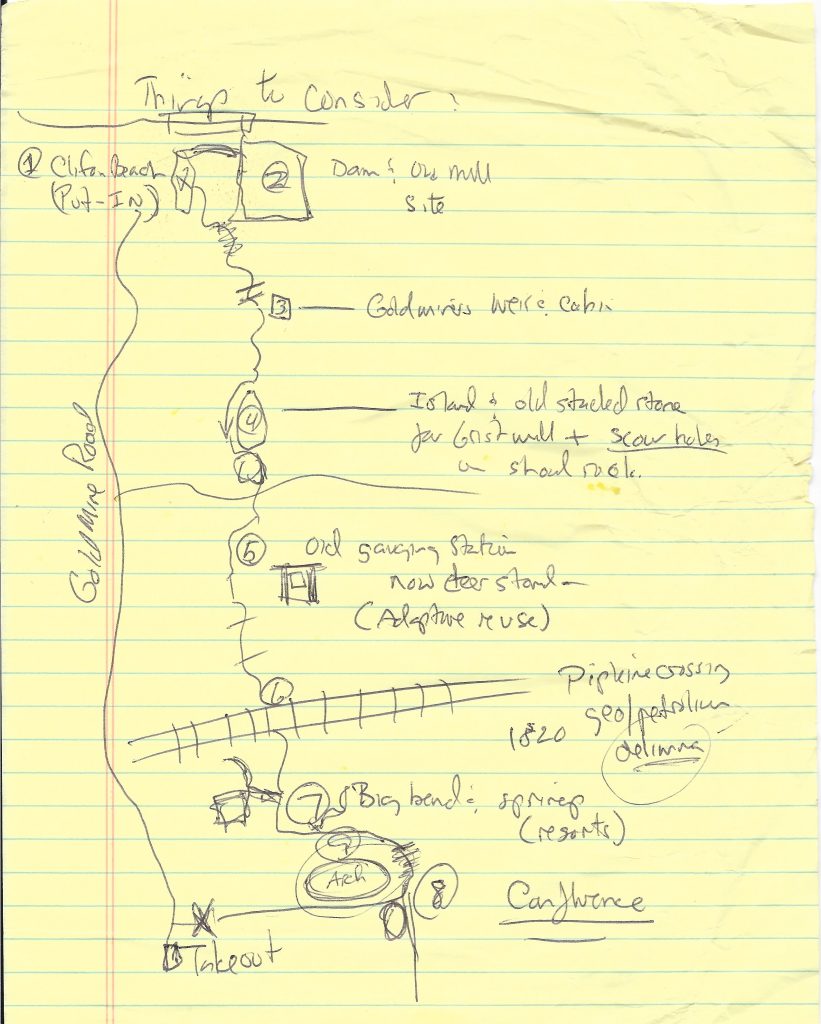

John hands me the map he’s drawn, “Start here and follow the current.”

John hands me the map he’s drawn, “Start here and follow the current.”

“And here are the sites I’d like you to note,” he adds. Or as his maps reads, “Things to Consider.”

- Clifton Beach

- Dam & Old Mill Site

- Goldminer’s Weir & Cabin

- Island & Old Stacked Stone for Grist mill & scour on shoal rock

- Old Gauging Station, now deer stand—(adaptive reuse)

- Pipeline Crossing geo/petroleum dilemma

- Big Bend & Springs (resorts)

- Confluence [with Lawson’s Fork]

The whole trip is no more than 3.5 miles and with a decent flow to the river from a very wet winter in the south, the trip shouldn’t take more than a couple of hours. We’d already left my truck at the takeout point before heading to Dolline’s, so take out and return were on an open schedule. I could linger, John encouraged.

Clifton Beach

“Damn it,” John growls. “Next time, I’ll put 50 pounds of concrete to sink this post for good.”

We’re looking down at the loosened, yellow metal post at Clifton Beach, a sandy spit of river front created by the old Clifton Mill dam. The posts are supposed to keep visitors from parking their cars on the beach, but locals sometimes dig up them up in order to park their trucks and cars, lawn chairs and coolers closer to the beach. John wiggles it around in its widened hole and shakes his head in disgust.

“Damn, damn,” he says again.

It’s nice to see John like this. I love his passion for his place, for this area is his place. He loves the people, the food, the southern dialect, the syrupy iced tea, and equally, the woods and rivers. He’ll get pissed off with a righteous indignation about abuse of the area and the rivers, like someone who not only loves them, but someone who believes—who believes that his life, writing and work are the good work that should change how folks get by with their woods and rivers. So when he’s saying damn, a bit of my old revivalist Baptist self wells up with happiness for him.

As I’m stepping into the kayak, he turns back to the post and how to make it right.

“Don’t miss the turn at the confluence with the Lawson’s Fork, or you’ll end up Pacolet Mills,” he laughs over his shoulder. What he means is that it’s a long walk back to my truck from there.

Dam & Old Mill Site

After I slide into the borrowed kayak, I push off from the sand and into the Pacolet and ease over into an old diversion run on the east side. The water is smooth and high enough for a good flow, but not so fast that I can’t let the kayak linger while facing upstream to take pictures and look at the old mill site.

After I slide into the borrowed kayak, I push off from the sand and into the Pacolet and ease over into an old diversion run on the east side. The water is smooth and high enough for a good flow, but not so fast that I can’t let the kayak linger while facing upstream to take pictures and look at the old mill site.

It’s mid-March, so the trees are not yet in their spring green. A few wildflowers are sprouting along the banks—I saw purplish “rose mole stipples” of trout lily leaves (nod to Gerard Manley Hopkins) and their tiny pale, yellow flowers during the day. Of course, daffodils and narcissi dot a few places along the bank where homes used to be. In my mind, though, I’m still hearing gospel songs and hymns.

“It Is Well With My Soul”

When sorrows like sea billows roll;

Whatever my lot, Thou hast taught me to know

It is well, it is well, with my soul.

The word “soul” is not an easy word for me to toss around—too many years of worrying about my salvation made me, uh, worry about its salvation. However, the increasing offerings of being a teenager in the 1970s and a youthful college night with a bottle of Mad Dog 20/20 and Kierkegaard wrangled me from my Baptist orthodoxy; the latter did little more than give me a lingering headache. A few months later, Emerson became my spiritual Tylenol offering, “The soul answers never by words, but by the thing itself that is inquired after. Revelation is the disclosure of the soul” (“The Over-Soul”). The “soul” is in the encounter, the revelation of your experience. And, for you poets, you’ve certainly worked with the koan of that first sentence in one fashion or another! It has taken me some years to relax into this definition—to give myself to such an experience as today, being offered by a dear friend a day to paddle a river, think back to the hymns flowing and eddying in my memory today, and muse and jot down a few words.

What a nice day to be alone on the Pacolet for a quiet float. Yes … it IS well, it is well, with my soul.

Goldminer’s Weir & Cabin

Weir Pronunciation: /wi(ə)r noun

- A low dam built across a river to raise the level of water upstream or regulate its flow.

Origin: Old English wer, from werian ‘dam up’ (Oxford Dictionary)

Goldmining in the 19th century was not only a west-of-the-Mississippi venture. The Pacolet River was also the site of dam and marginally successful gold mining effort. Goldmine Road skirts the western bank of the Pacolet and the remnants of the weir span the width of the river. Newspapers from the time suggest some gold was taken from the river, but also hint at secret stories of even greater hauls. No one is panning for gold these days; the Pacolet, like other rivers in the Piedmont, was always more valuable for mill power and dispersal of waste than for precious metals. Upstate South Carolina rivers, such as the Pacolet, Lawson’s Fork, and the Tyger, were little more than drainage ditches until the Clean Water Act and the textile industry leaving for cheaper labor costs. For the last thirty years as the rivers have been recovering, John and other activists have been asking locals to return to these rivers and experience them for more than monetary profit. I have a paddle in my hands, not an oar, because I’m not looking for ore.

He will hold my head above;

I shall through the waves go singing,

For one look of Him I love.

If I’m mining, I am augering past myself, perhaps an augur to something more. Why mine a river that might carry the best of me with it? There is so much more in it, than gold I might take from it.

Old Gauging Station, now deer stand—(adaptive reuse)

About halfway through the trip, off to the left-hand side, is a small cabin sitting atop an old gauging station. It’s used now as a deer stand—about as cozy and spacious a deer stand as I’ve ever seen. I imagine lounge chairs and coffee tables, more than one deer head mounted on the walls—nice hickory paneling and perhaps a propane-cooler keeping the beer cold.

The first gauging stations in the US began in the late 19th century to measure water flow discharge during heavy rains in order to forecast dangerous flooding—later these stations also measured water quality and river health and biodiversity. Over the years some of these have been upgraded, replaced, or abandoned for less imposing structures and more accurate instruments. There are around 23,000 stations throughout the US and Puerto Rico. If you paddled a river in the US, you’ve likely passed one or two, whether you noticed it or not.

It is a strange and somewhat disarming sight, the gauging station with a big chunky cabin sitting atop, remade to serve another purpose. However, floating a South Carolina river is to study such experiences; most of its rivers are not wilderness per se, but paddling them is often encountering the awkwardly wild. Paddlers constantly float into events and through places that feel more like a non-sequitur than a narrative—something like a picaresque novel sprinkled with Monty Python skits delivered in a James Dickey smile and drawl. For instance, I came across what I call in my journal “the island of forgotten tires”—a small sandy island dotted with 6–8 tires.

There isn’t a particular reason the tires should be parked there—no road leading to the Pacolet making for easy dumping, no flow to the river that has driven them to that spot. I don’t know that one should reconcile such things (especially as litter) as much as you make sure you encounter them over and over. Action then, like satori or salvation, becomes more clear, and yet nuanced, creative, and perhaps guided by something more than ego.

“Like a river, glorious …”

“The poet can never sink and, be sunk, while sunk, be Poet. His diving is always a dive, even if to do it he must sniff the vapors in his oracular cave—or otherwise drastically wrench himself open that the whole river flow through.”

“The poet can never sink and, be sunk, while sunk, be Poet. His diving is always a dive, even if to do it he must sniff the vapors in his oracular cave—or otherwise drastically wrench himself open that the whole river flow through.”

(Draft of a Letter to Robert Duncan)

Bixby Canyon, July, 1962

Lew Welch

Is God’s perfect peace,

Over all victorious

In its bright increase;

Perfect, yet it floweth

Fuller every day,

Perfect, yet it groweth

Deeper all the way.

I wish I could give you the second hour of my float trip like I could give you a picture moving and full of motion and sound, a recorded song playing over and over until you feel how the fingers touch the keys, the happiness the pianist offers in playing it. I wish I could give you the time it takes so that our phones lose reception, our email becomes faint memory, and we begin, by some miracle or delusion, doesn’t matter, to re-imagine a paddling trip as joyful work, work in a place, work on one’s self, work for others, for all others. I wish I could give you the galax and doghobble painting the rocky riverbank in green blotches and the pileated woodpecker’s tapping which, when I am there and receptive, become the first lines of paragraphs of what I’m writing.

It takes time to lose yourself to the flow of a river, until you can lean back in the kayak and stretch your legs out to the sides, keeping perfect balance because you’ve found your comfort and connection to the boat’s movement, letting the sun wash your neck and face, the herons and egrets staring stick-still as you drift by, the feral domestic ducks clicking their bills near the boat, the creaking oak limbs in a spring wind, the sound of water over rocks becoming melody.

How does a person “wrench himself open that the whole river flow through”?

Get out there and see, listen, relax, stretch out after a while, work at it, so to speak. Then, don’t work at it. Begin to drift, hear water, forget all where you came from and that’s off the river, and remember the something in your childhood outdoor rambles that gives you permission to be at peace. Let words such as “nature” and “spirituality” compost into what nourishes the future. Let yourself forget your self.

Get out there.

It might come to you.

Confluence with the Lawson’s Fork

Way up in the middle of the air

Ezekiel saw that wheel

Way up in the middle of the air

Now the little wheel runs by faith

And the big wheel runs by the grace of God

And a wheel in a wheel

Way up in the middle of the air

Fifteen years ago, I had started a river trip farther up Lawson’s Fork and made my first stop here at the confluence with the Pacolet. Then, there was a large sand bank to pull the kayak onto; now, there was only a small beach. That stop was a turning point in my life, knowing I’d likely leave Spartanburg in the not so distant future, and while rivers may be old, they are not nostalgic—things shift and change (thanks Heraclitus!)—so the once important shore in my life is now worn to almost nothing.

The right-hand turn from the Pacolet into Lawson’s Fork isn’t a hard one right now, the current is light and the brush and log jams minor. It’s only a couple of hundred yards to the take-out below Goldmine Road, so I’m taking my time getting there, taking in the past, taking in today. It has been a glorious day.

For whatever reason, some long dormant synapses start firing and I begin hearing the old hymn/spiritual “Ezekiel Saw the Wheel.” The church music director had worked with the choir for two weeks practicing an additional 30 minutes Sunday afternoon between morning and evening services and after Wednesday evening prayer service. The music director and the pastor must have coordinated because only once during the entire 17 years of my growing up in Baptist church did the pastor offer a sermon on Ezekiel’s vision and the complexities of four-faced creatures and the wheel within a wheel. I don’t remember much about the sermon, but this repeated line stuck with me, “…for the spirit of the living creature was in the wheels” (Ezekiel 1:20-21). If you want to lead yourself down a really windy path of gyroscopes, biblical interpretation, Pythagorianism, mysticism, Jungian psychology, UFO sightings, and even stranger readings of Ezekiel’s vision, go ahead; I’m stopping at that trailhead. However, what fascinated me then is what fascinates me now—this idea that spirit/soul of the creature was in the wheel within the wheel.

The chorus of the hymn goes:

And the big wheel runs by the grace of God

Today’s float has been wonderful, in part, because I had faith it would be, faith that if I was patient enough and immersed myself into the trees and birds, flowers and deer stands, weirs and riffles, hymns and riversong, and ironies and beauties I’d find something of that soul Emerson tries to point me to. But this is the “little wheel,” for the big wheel is run by something far bigger than my faith. Call it “the grace of God,” “nature,” or “over-soul.” Doesn’t matter, but something bigger that doesn’t require my faith is spinning away whether I choose to notice or not. It is my job to experience it—by naturalist studies, by environmental science, by art, but mostly, by experience and faith in that being in the non-human world with some time, then something might happen that might be … heaven forbid I use this term … spiritual. And perhaps, best, that word, fails too.

Today’s float has been wonderful, in part, because I had faith it would be, faith that if I was patient enough and immersed myself into the trees and birds, flowers and deer stands, weirs and riffles, hymns and riversong, and ironies and beauties I’d find something of that soul Emerson tries to point me to. But this is the “little wheel,” for the big wheel is run by something far bigger than my faith. Call it “the grace of God,” “nature,” or “over-soul.” Doesn’t matter, but something bigger that doesn’t require my faith is spinning away whether I choose to notice or not. It is my job to experience it—by naturalist studies, by environmental science, by art, but mostly, by experience and faith in that being in the non-human world with some time, then something might happen that might be … heaven forbid I use this term … spiritual. And perhaps, best, that word, fails too.

I’m smiling now from my day. I’ve probably said enough.