When they next wake, all this derision

Shall seem a dream and fruitless vision…

William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

It’s Day Three of the Upward Bound program on which I’ve been hired to teach for the summer, and the boy with the Usher-like face and soulful eyes is asleep again at his desk, his head swaddled between the folds of a college sweatshirt. He makes no attempt to disguise his intent to snooze through the entire two hours of my class, but I don’t take it as a slight; he seems genuinely incapable of unshuttering those velvety, adolescent lids. Either he’s hampered by chronic lack of sleep or his mom gave him Benadryl to counteract the raging ‘yellow season’ that’s in full bloom outside: that, or it’s some weed-induced stupor. Any of these scenarios is possible. Maybe he, like many of the kids here, has had to work late at some out-of-town McDonalds, Church’s Chicken, Zaxby’s, somewhere minimum-wageish and fatal to a young person’s sense of potential. The kind of place I have managed, in my culturally fortressed world, to avoid.

Never has a student in one of my classes fallen asleep so openly, cartoon-like on the desk. I should feel disrespected, except this young man doesn’t eye me, as one or two of the other kids have, with disdain. He doesn’t, in fact, look my way at all.

Though I’m supposedly the authority in the room, I can’t question him; there’s no available protocol, and it doesn’t, in any case, feel like my business. I am merely the instructor here, an upstart immigrant from Britain who’s come in to provide educational opportunity in exchange for a wage, in truth, not much better than some greasy fast food living. An improvement, it’s true, on the $12 an hour I’ve agreed to pay the sitter I’ve left at home with my two small children, bargaining her down from $15, and afterwards feeling the sting when I saw the woeful condition of her car. Later, I will have to fire her because—probably as a result of her transport woes—she’ll fail on one too many occasions to turn up on time. I’ll sob into my sheets that night, my alien face puffy with the miserable, oppressive wrongness of it all. For she, like every one of my students, is black. She inhabits a world through which I have never traveled: more correctly, that world has been there for me to visit all along, but I’ve rushed through it on a train full of passengers lulled to sleep by the soothing, clickety-clack soundtrack of our shared whiteness.

I did not want to relocate southwards. I’ve followed my husband here from England via Vermont, California, and the Midwest so that he could progress on the unpredictable walkabout that is his academic career. I’ve given up full-time teaching along the way to care for our children, and it’s fair to say that I am lost. Dantean, dark woods kind of lost. It’s just possible, too, that I’m suffering from postpartum depression. At home, when I haven’t been distracted by concerns maternal or pedagogical, I’ve been staring out at the unfamiliar trees and remorseless heat, wondering How? I know no one, and now, each afternoon for five weeks, I have to leave my baby and preschooler at home to report for duty before two large groups of strangers, many of them less than thrilled to spend their summer in a super-heated classroom, writing poetry.

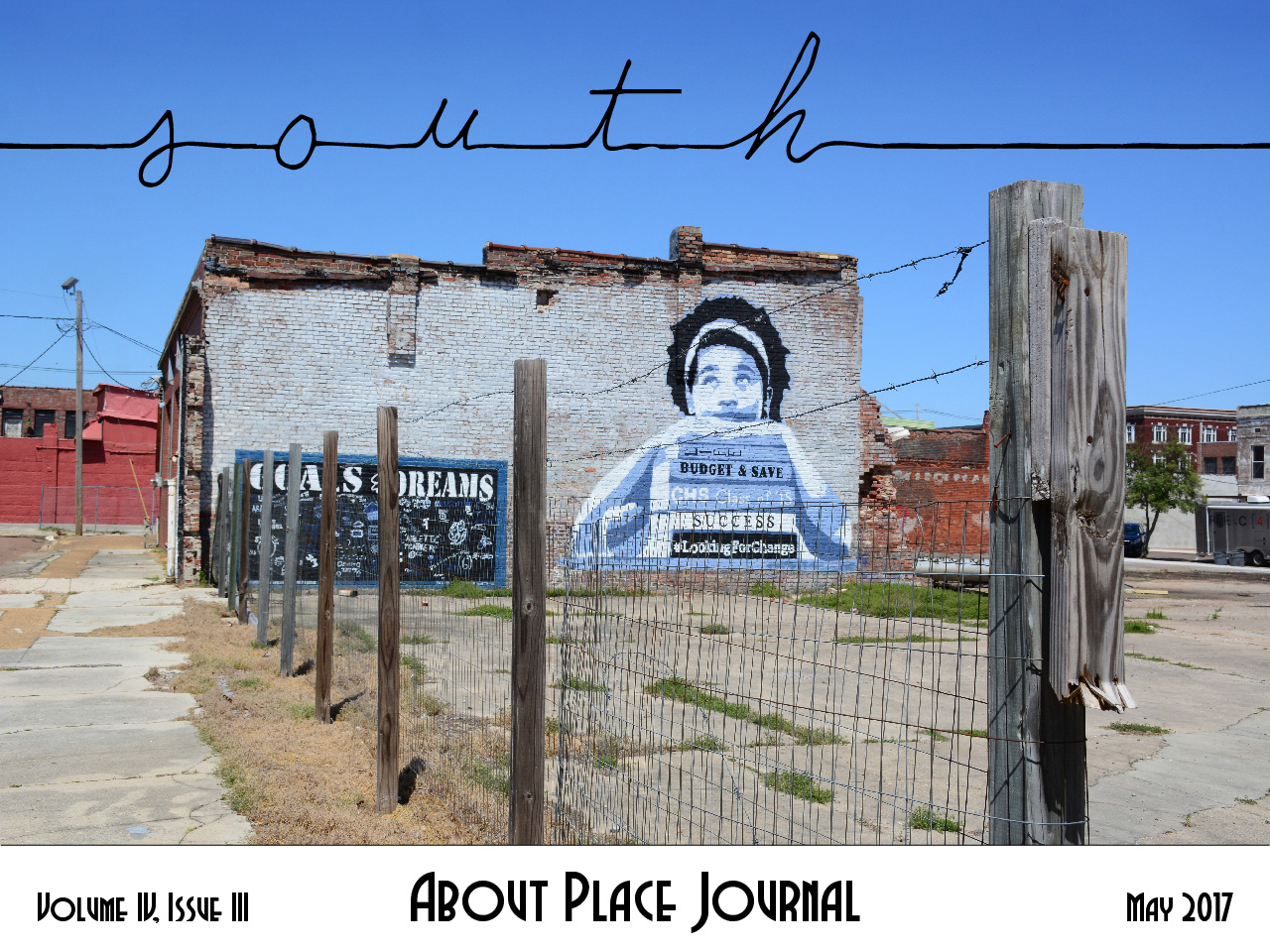

The Upward Bound program, a federally-funded effort to help first generation college hopefuls, is housed in the Booker T. Washington building at the very bottom of the university’s high scholastic hill. The paint is peeling; the air conditioners are broken. They rattle. They gasp. The temperature outside regularly hits 100°C. I’m told that ‘Booker T’ recently survived a fire, but no one will talk about who might have started it. (How far must the heat rise, I wonder, before things self-combust?) No one tells me, either, that this was once a historic black high school, closed thirty-six years earlier to a furor, most of the buildings demolished without any plan to commemorate their importance. Now, as a result of the conflagration, boxes of salvaged books and equipment line the hallways. I’m reminded of the attic room I once rented in South London, which lacked a stovetop, a bathroom door, and, most crucially, a fire escape.

I make a mental note to read up on Mr. Taliaferro Washington. While I remember vividly my history lessons on the slave trade—those blurry, mimeographed cross-sections of the terrible ships—my education included little of my predecessors’ murderous roles in it, and not a word on the inspirational exploits of black abolitionists or African-American pioneers, though I know all about William Wilberforce. Francis Drake was always presented as a swashbuckling, be-ruffed hero who threw his cape over royal puddles. Sherman and Lee? Lee and Sherman? Remind me again, please, which is which.

In England, I see it now, I was not worldly, as we’d been led to believe. But, like my teachers, half asleep, one eye fixed on the white world, the other sealed firmly shut. No surprise then that I’m struggling to motivate my classes, having a hard time reading the group, who look at me when I arrive each afternoon as if I’ve wheeled my way in from Pluto, as if I am, in fact, that demoted, who-cares? planet.

At least there it would be cooler.

Nothing in my lengthy experience as a classroom teacher has taught me how to deal with an unrousable teen. From my seat in the circle into which I’ve arranged the desks—a layout that’s further disoriented the kids—I try to assess the situation:

- I am English and my students are not.

- I am new to the South, while they were born here. All except the boy from New Jersey, whose father is in jail: whose cousin, he’s told us, on Day Two, is dead.

- I am almost three times their age.

- No one in my family has been incarcerated.

- Or shot.

All we seem to have in common is our mutual state of confusion: our general discomfort.

What to do?

The young assistant I’ve been allocated steps up behind the sleepyhead’s chair and tells him to stand behind it, a demand with which he lazily complies. My stomach churns. Can’t we just send him home to catch up on his boyish slumber?

“I’ve always wanted to do this kind of work,” I’ve persuaded the hiring executive a few weeks back. Devastatingly well turned out, she was apparently immune to the heat, her suit immaculate, her hair a picture of chic restraint.

“I was a scholarship kid myself,” I chirped hopelessly, unpeeling sticky thighs from the chair. On the application form, I’ve actually quoted Gandhi: Be the change you want to see in the world. The pallor of my skin, I knew, might be an issue, but surely the color wheel would spin us all into a centrifugal blur once it got going: once we got to know each another. This is what I learned from my years in London, that pick-and-mix bag of global candy and multiculturalism. People can weave their lives together. But in reality I’d found it impossible even there to make friends of other races: everyone with whom I’d attended college was white; almost everyone I’d ever worked with. When I tried to ‘mix’, more often than not I overcompensated. I joked too much, moved in too fast: a drunken desperado after hours in some shabby Westway dive.

This, in any case, is not London. Nothing I’ve encountered before, not teaching the underserved children of the English provinces, not working in Brixton during Margaret Thatcher’s riot-inducing tenure, nor my occasional contact with minority and underserved communities across the American Union, has prepared me for this particular challenge.

Here, a freckled, female Paul on the road to Damascus—on the poorly maintained road, in fact, to Booker T. Washington—I am a learner driver, dangerously unschooled. As I wheel my way down Wheat Street, past Sumter, Marion, Hampton, Richland—roads named for Confederate generals and plantations—the sunscreen I’ve plastered onto my ill-adapted skin dissolves in sweat and ambushes my eyes. Back home, I was often exceedingly wet, or even on occasion too hot, but I never suffered the two states at the same time.

In the distance glitters the dome of the new Strom Thurmond Wellness Center, a mausoleum of tinted cement and glass whose fees I can’t afford. Strom Thurmond: filibusterer supreme of the Civil Rights Act, and another figure whose name is new to me. Later that year, it will appear in the papers as belonging to the man who disavowed his own ‘secret’ black child, Essie Mae Washington-Williams, aged 78. But only long after Thurmond has died: only after that palace of elite recreation has been forever dubbed ‘The Strom’.

My students can’t understand why I would cycle to work. To them, such a choice is anathema, a symbol of the deep poverty from which they are trying to escape. I’ve seen older black men wobbling on trick bikes along the perilous gutters, holding on hard in the wake of the SUVs. They ride, always, against the traffic, for safety perhaps. Or as an act of rebellion. It seems rude to ask for clarification.

“I do it to keep in shape and save money,” I tell the kids: “To help the planet.” I need to mitigate the effects of all the driving I do, ferrying the children back and forth to the school of choice at which my husband and I have enrolled them: the school that lies on the other side of town and is 80% white, unless you count the teachers, in which case it’s more like a 95-5 split. On the morning of Obama’s first election, I looked in vain for someone with whom to share a victory smile.

No one seems to know quite how to categorize me: whether I’m a joke or an oddly dressed threat. When I first arrived at Booker T, a ninth-grader in a brightly colored waistcoat barreled up to me in the hallway, tugging her friend by the sleeve:

“Are you our teacher?” she demanded.

I stopped to smile. “Yes, I’m Nicola. What’s your name?”

She eyed me with suspicion, then shot her friend a cool glance. “You foreign?” she asked extravagantly, pushing back her pretty shoulders.

My students are varying tones of copper and ebony, their hair dressed in shining flat-ironed ringlets or neat Afros, whereas I am pink speckled with caramel, topped with the humidity-frizzed, light orange hair that once caused my elementary school classmates to taunt me with ‘Ginger.’ It was a benign enough epithet, if it hadn’t been applied with such biting, impious force. But I can’t pretend to understand: it’s the degree of venom that matters, I know, its inescapability, the implications. I have been lucky.

Foreign. Yes. And though I’d like to disregard the obvious differences in our origins, they circle above us like the raptors that frequent the towering pines of our local park—we’ve seen, with the children, a hawk snatch an unsuspecting squirrel clean out of the branches and whack it against the sandbox till its head flew off: ‘Time to go home.’

So. Day Three. I begin that day with a classic exercise. Write down three facts and a lie.

“We’ll share,” I say, “but it’s okay to pass.” The usual rules.

It’s okay to pass. Good grief.

In my fancy French notebook, I scribble down my own confessions:

- I once sent a love letter to a famous actor (a dangerous habit of my youth, true, alas);

- I’ve been a cover girl (I was four: my father had connections);

- I believe in miracles (my late-won babies; my own survival. Corny, perhaps, but true.)

- I’ve always wanted to be taller than I am.

My lie, until today perhaps. In the past, my smallness has lent me certain advantages—made me less threatening and given me the option of hiding. I trust they’ll pick out that last one in any case. Who wants, after all, to be small?

The group seems surprisingly willing to share their personal factoids, excited even—awake! But most of what they reveal is simply sad. The lad whose father is in jail reveals he’s received that week a letter, but hangs his head in disappointment. One young woman, playing with her tousled hair, confesses her boyfriend committed suicide five months ago, and she’s considered following his example. She sits close to me, urgent, as I once was, to drink from the teacher’s cup. Can I quench that thirst fast enough? All their thirsts?

Sometimes I miss a particular idiom, an unfamiliar dialectical riff, and have to ask a student to repeat himself. Sometimes, even then, I have to pretend. We are speaking, in so many ways, entirely different languages, and I know if I reveal my ignorance of theirs, or push them to understand mine, I’ll lose them: I’ll further distend the generational and cultural balloon that hovers between us, threatening at any moment to explode and go phut-phutting off into the rusting rafters.

There are still twenty-two hot afternoons to go.

When it’s my turn to share, and I get to my ‘cover girl’ admission, the girl in the waistcoat snickers loudly:

“Well, we know that one’s not true.”

A titter passes round the room, along with a general sucking in of teeth and one or two concerned glances. I try not to react. They’re teenagers. But I can feel a regiment of angry beetles gnawing at my ribcage, whittling away at my sense of self-worth. It’s hard not to take it personally, not to connect the comment to my age or character or appearance, or—

The lesson stings: it threatens to shut me up and makes me crave invisibility. The feeling is part shame, part disillusionment, part self-doubt, part hatred—both of the self and of the attacker. Something like the way I felt as a child when my older cousin cornered me in my bedroom and demanded I remove my underwear, no point in crying out. In such moments, the body becomes grotesquely foregrounded so that its very existence causes discomfort: no longer a sanctuary, it’s forced to open itself to the rampaging masses, now free to enter and crush underfoot the immaculate spirit within, to trash it and simply walk away.

I don’t and can’t understand the experience of being black in America, or in any other place for that matter; it’s something at which I can only, very poorly guess. But here’s a crack in the door; a draft of magic wake-up juice tipped into the white, the English eye.

I hold tight to the scrap-edge hem of my mission.

The next day, we list our ambitions—‘dreams’ we call them. My students want to be lawyers, nurses, accountants, photographers, big-time basketball players, or computer technicians, zoologists, surgeons, architects, bio-engineers, Broadway stars; valedictorians.

“I believe in myself,” write the black kids from the South; “I have big plans and plan on executing them”; “I want people to scream my name loud”; “Love me or hate me, I’m still going to do me”; “Better than my mother and father had did with their lives. Without their mistakes, I wouldn’t have no fire to awake my dead dreams, which are now alive.”

“My dead dreams, which are now alive.” I write that down in my notebook.

“If Plan A don’t work out,” writes another of the girls, “then on to Plan B.”

A prescription.

When I breeze in the next day, the air has gone rigid. The girls have got themselves into some kind of trouble; one of the boys has set fire to a bag of popcorn in the dorm microwave, and they’ve all been grounded.

“What’s going on?” I ask, and they talk about the tedium of the long hours in class, the insufficiency of their checks. Checks? Later, someone will explain. The students are being paid to come here. Without the stipend, these kids would have to work; they would not come. The money is an incentive, a payoff to set against time spent away from the workforce: the teasing they’ll get for trying to better themselves the only way our society has decided you can. For attending college; for ‘acting white’.

Surely, I think, Booker T., educational reformer and Presidential advisor, must be spinning in his Alabama grave. Or, then again, maybe I’m wrong. Maybe he would, if he could, jump up to offer himself as signatory. A business-minded, gentlemanly flourish.

At the end of the second week, the program director announces that he will address my class, he’ll try to talk the less engaged kids out of their stupor. I know this will undermine my authority, diminishing what little ground I’ve gained, but he seems resolved. At the inaugural staff meeting, he told us point blank that he didn’t want the directorship, but no one else would take it, what else could he do? He cuts a dashing figure with his slender frame and fine physiognomy, and were I not married… but he looks uncomfortable in his body, as if someone has filled the world with cheap beer, or illicit moonshine, and kept forcing him to gulp it down.

Okay, I say. He’s a decent man: I can learn from watching him.

We’ve just finished our warm-up exercises when he appears at the door, a sheaf of photocopies in his hands. He doesn’t return my smile, but strides to the front of the class, leaving me to hover behind him, trapped by the big table across which are strewn postcard images from the Hubble telescope that I’m planning to use as prompts, the universe being something to which we can perhaps all claim equal ownership.

“Pass these out,” he barks at the kids, shoving the papers in their hands, and they do as he says, uncertain. I look at their faces to see how they respond to him, but I can’t tell. If anything, they seem disdainful: he is the one with the power to punish them.

The director gives me the remaining handout, then flaps his copy in front of the class. “Someone read this,” he demands.

I glance down. It seems to be something he’s found on the internet. At the top of the first page, in bold capitals, appears the title THEY ARE STILL OUR SLAVES.

Everyone freezes.

The boy at the front looks around in a panic, then sounds out the words suspiciously.

“Go on,” snaps the director.

“We can continue to reap profits from the Blacks without the effort of physical slavery,” reads the boy, glancing up for rescue. “Look at the current methods of containment that they use on themselves: IGNORANCE, GREED, and SELFISHNESS.”

His voice fades. “What is this?”

“Just read it,” demands the director, and the boy does, his tone flattening out as if he’s decided to block out the meaning of the words: to say them as if they’re a shopping list, a math text, the pledge of allegiance. He has learned this much.

The article goes on to declare, “the best way to hide something from Black people is to put it in a book,” and I begin, horribly, to see the intention—most of the students have resisted reading, doing their homework—but I feel as if I’m present at a public flogging. Then one of the younger boys, a freshman who’s been giving me the runaround, who I forgive because he’s fifteen and full of a not unappealing energy—jumps up. “I’ll read,” he says.

“Blacks, since the abolition of slavery, have had large amounts of money at their disposal,” goes the text. “They would rather buy some new sneakers than invest in starting a business. Some even neglect their children to have the latest Tommy or FUBU.”

He knows, unlike me, what a FUBU is. His shirt is shiny new, a shout-it-out dayglo orange; he’s the only one from either class who appears to have money. He’s flashed around his new MP3 player and laughed at my ageing cell phone; he’s bragged about the three houses his father owns, and about his family’s costly vacations. Why not? Except the other kids, on those occasions, have gone quiet.

“SELFISHNESS,” he continues, regretting now his eagerness, “ingrained in their minds through slavery, is one of the major ways we can continue to contain them.”

We: as in the bigots who use the internet to spew out this kind of hateful drivel; Them: the youngsters with whom I’m trying to connect. I’m not directly implicated, but I feel sick to my stomach, as if the director has aimed a wrecking ball in my direction and smashed through everything I’ve worked to build.

Should I leave?

But there is a second page.

“Someone else!” comes the directive.

By now, like me, the students understand this present torture will end only when we get to the end of the article. One of the more studious girls picks it up, her voice a monotone: “We will continue to contain them as long as they refuse to read, continue to buy anything they want, and keep thinking they are ‘helping’ their communities by paying dues to organizations which do little other than hold lavish conventions in our hotels. By the way, don’t worry about any of them reading this letter, remember, ‘THEY DON’T READ!!!!’ ”

There is silence.

“Well, what do you think of that?” The director’s face, like my body, like the whole room, is burning.

I glance up at the students, their frantic eyes. They look like guppies splashing in a pool of sharks.

“Come on,” heckles the director.

“It says you have to think about more than money.”

“What else?”

“It says you need to respect yourself.”

“Okay, respect. What does respect mean?”

“It means loving yourself.”

“It means listening to your parents.”

The boy in the orange shirt looks me straight in the eye: “It means we have to listen to Vanilla Face,” he says, and a broad smirk spreads across his young face.

His words smash against my unguarded, unaccustomed, privileged chest. I wait for the director to come to my defense. The boy is just testing; surely my boss will use the moment to say something about epithets—to teach about universal respect. But none of this happens. Quietly, almost imperceptibly, an amused sneer creeps in at the corner of his mouth. He meets the gaze of the boy who’s offended me and I see his own eyes twinkle. “Okay,” he says, half creasing his brow in a gesture of amused semi-chastisement, and then to the class, “Okay. So what are you going to DO?”

“Be more respectful!” they chant.

And then we write poems about space, about nebulae.

At the peak of the summer, when the heat, and studying, has got too much, I usher the kids into a cool, windowless TV room and show them a movie: Baraka. It’s a documentary collage, a fabulously edited sequence, showcasing people of various faiths and ethnicities engaged in acts of worship: priests and rabbis, imams and monks. In the central and most compelling scene, two large groups of men decorated with tribal markings sit cross-legged, facing one another in a jungle clearing. In the shadow of a towering Mayan temple, each group first raises their arms heavenward and ululates, before pressing their bodies silently forward, the two groups bending alternately toward one another and then away in what appears to be, to the outsider, a confounding ritual.

Watching it makes me anxious and afraid: the anticipation, my ignorance.

“What are they doing?” shouts one of the boys from the darkness, and I’m not sure how to answer him. I think perhaps they are preparing for some unspeakable rite of passage, or getting ready, perhaps, to kill one another: an incitement to war. Then one of the girls up at the front—one of our class ‘sleepers’—bolts upright in her seat and bows in toward the screen, watching intently, before announcing in an awed whisper:

“They’re blessing one another.”

“What?”

“What did she say?”

She turns round then to face her classmates, her eyes wide, and shouts it loud: “They’re blessing one another.”

Of course: Baraka. I should have seen it—looked it up—but it’s this young girl who’s interpreted the mystery for all of us. I should have trusted that, each in our own time, we’d wake up and see: that we’d be led by the least likely of the crowd.