a literary journal published by the Black Earth Institute dedicated to re-forging the links between art and spirit, earth and society

Starr Goode

The Power of Display: Sheela na gigs and Folklore Customs

Whatever the original purposes of the Sheela na gigs, over the years many folk customs have become associated with the figures. The debate about their meaning started in the 19th century when Antiquarians were stirred by a passion for things of the past. Puzzled by these strange images, they began to question why carvings of nude females in brazen sexual display of themselves appeared on medieval churches throughout the islands of Ireland and Britain. In the popular belief of country people, Sheelas were employed to help with fertility, to heal, and to bring good luck. These later rural traditions expanded on the Sheela’s first use as a guardian rooted in the apotropaic display of her naked sex. Such folk customs are not just local but reflect the universal numinous energy in the image of the vulva.

One of the first female scholars of the Sheelas, Margaret Murray, in her 1934 “Female Fertility Figures,” calls them fertility figures belonging to a category of goddesses she names the Personified Yoni. In a refreshing analysis, she sees the erotic quality of the displayed vulva as not only stimulating to men but to women, too! She also cites the folk custom of brides on the way to their wedding looking at the Oxford Sheela to ensure a fruitful marriage.1 Edith Guest states flat-out in the 1937 journal of Folklore that the Sheela na gigs are fertility figures and reports that the Castle Widenham Sheela has been “frequently touched for help in childbirth within very recent years.”2 Such practices still continue as witnessed by an account given by James O’Connor in his 1991 monograph on the Sheelas. The eccentric, long-time owner of Kiltinan Castle ( known locally as Mrs. La!) told him while he was in his teens that the two Sheelas in Kiltinan “represented an ancient fertility goddess and that barren women used to scrape the stone in the churchyard for its healing dust.”3

In her 2004 book, Sheela-nag-gigs: Unravelling an Enigma, Freitag contends that the central function of the Sheelas was their use as “folk deities in charge of birth.”4 In her view, these rural mothers-to-be, in their time of need, turned to a belief in the magical energies of the Sheelas. Freitag also makes a compelling point that the Church had allowed for the presence of these heathenish, certainly not Christian figures, as a way to subdue and control the rural population. The Sheelas were part of a folk religion “too important and too intimately bound up with the welfare of peasant communities to be disregarded by the Christian Church.”5 For beyond their aid with parturition, Freitag writes that the Sheelas ensured “fertility in humans, animals, and crops.”6 The life-giving powers of the vulva guaranteed that nature would continue to be fruitful. The Sheela na gig’s authority comes, of course, from her revelation of a primal if not the primal symbol of creativity.

Guest, in her thorough taxonomy of “Irish Sheela-Na-Gigs in 1935,” records other folk traditions about the supernatural powers of several Sheelas. At Carrick Castle, County Kildare, the figure was characterized by the local people as an “Evil Eye Stone” to guard against unwanted influences; a Sheela at Cloghan Castle, County Offaly, was known by the peasantry as “The Witch” even into the late 19th century.7 In her 1937 Folklore article, Guest chronicles the stories and customs around many Sheelas, often involving a holy well and a magical shrub or tree.8 These remnants of a powerful belief in the image may be the the last records of the tip of an iceberg of customs no longer available for our understanding.

Guest ends her 1935 catalogue of the Sheelas with the observation: “But that pagan ideas and practices were associated with these figures in comparatively recent times and are so even today can hardly be doubted.”9 The word pagan has the familiar definition of non-Christian people (derogatorily called heathens), but its etymology from the Latin paganus, “of the country, rustic,” carries a second meaning also connected to the Sheela na gigs. After all, the Sheelas are not an urban creation but exist mostly in the countryside. It follows that rural people living more intimately with natural instincts would form unique ties to these earthy figures so well known to them over the centuries.

In popular belief and practice, the Irish did not lose their awe at the sight of displayed female genitals. In 1843, Johann Georg Kohl, a German writer, published the results of his two months of travel in Ireland seeking out the Sheelas. Fascinated by the carvings which the superstitious Irish thought could avert ill luck, he discovered that the Sheelas existed not only as stone monuments on a wall but also as living women! For those caught in the spell of the evil eye, their affliction could be lifted and good luck restored by these wise women. Just how? By lifting their skirts to display their female nakedness: “These women were called and are still called ‘Shila na Gigh.'”10 Kohl perceptively noted that with the deeply rooted Irish customs, “If anything ever existed in Ireland, so can one almost always believe that it is the same now.”11

An even earlier reference to the existence of human Sheelas comes from the 17th century in the diocese of Kilmore. A synod or council refused to offer sacraments to a category of women known as gieradors, who might be called “living sheela-na-gigs.”12 Weir and Jerman believe this reference gives evidence that in some rural areas Sheela-na-gig was a name for “women of loose morals or simply old hags.”13 To the Church, was it a crime for a woman to lift her skirts or to be an old woman? Could the powerful women who so interested Kohl two hundred years later be the descendants of the earlier gieradors banned from the church?

Closer to our time, in the twentieth century, the traditional belief in the power of the naked female display still persisted in the Irish countryside. In a letter to the Irish Times dated September 23, 1977, an old man, Walter Mahon-Smith, recalls an incident of his youth: In a townland near where I lived [Caherfinsker, Athenry, Co. Galway], a deadly feud had continued for generations between the families of two small farmers. One day, before the first World War, when the men of one of the families, armed with pitchforks and heavy blackthorn sticks, attacked the home of the enemy, the woman of the house (bean-a’-tighe) came to the door of her cottage, and in full sight of all (including my father and myself, who happened to be passing by) lifted her skirt and underclothes high above her head, displaying her naked genitals. The enemies of her family fled in terror.

Another twentieth century story comes from Guest at the end of her 1935 catalogue in Appendix IV, “The Term Sheela-na-gig.” She indirectly affirms the ancient custom of females displaying themselves to dispel evil and that such females were called Sheela na gigs. From her travels in the Irish countryside to conduct research, Guest recalls a time when she used the term to a woman from a long line of farmers in the Macroom district. The woman “derived some puzzled amusement from it [Guest’s reference to the stone figures], wondering why I should desire to seek out old women of the type which I may describe for brevity as ‘hag.'”14 From her early childhood she had known the word as a common one used by people with this “connotation” of the human Sheela na gigs.15 It seems that the professional Sheelas were elderly women. Andersen speculates that the name Sheela na gig was originally a folk term concerned with the ritual of display performed by these women and “not with the witches on the church walls.”16 Does this mean the stone figures took their name from the living Sheelas and not the other way around?

A thread runs through all these examples. Once again the Sheela, whether made of stone or flesh, evokes the image of the old witch, a link to powers of the dark goddess capable of destruction in the service of regeneration. Such powers were forced underground by the patriarchy, or as Jørgen Andersen puts it: this is the “last survival of an ancient practice, that of displaying the genitalia as a means of opposing evil, slighting enemies, etc. Trust the Irish to have treasured such a relique and to have kept it very much in the dark.”17

Nineteenth century antiquarians documented the remnants of local legends and old names by which rural people called their Sheelas; as if from another epoch, some of these figures have been missing for over a hundred and fifty years. Yet traditional practices around some Sheelas continue to thrive in our time. Pilgrimages to the sites of the holy well at Castlemagner and to Gobnait’s Abbey, both with Sheelas and full of pagan associations, remain popular. Often no recorded folklore exists connected to any particular Sheelas and never any text to explain their function; we only have the appearance of the figure itself, but that is enough. One singular Sheela, alas, no longer in situ but in the confines of the National Museum, deserves special attention, the Seir Keiran Sheela na gig.

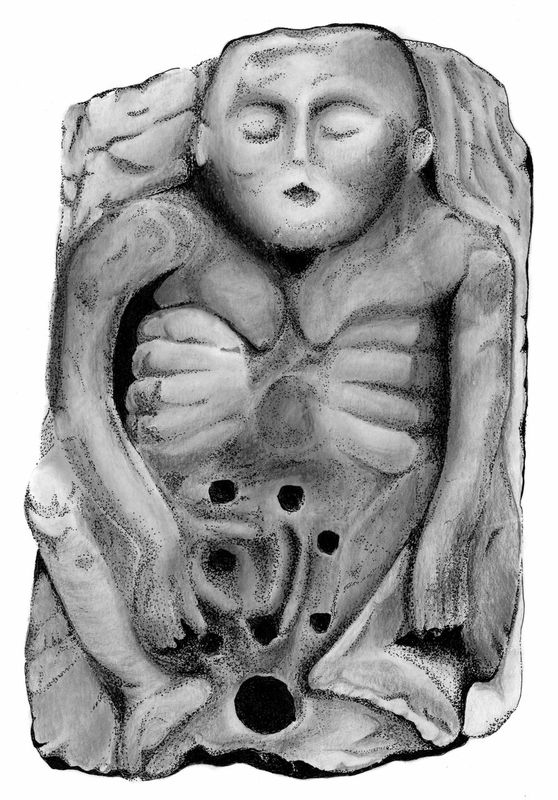

Originally from a church just south of Birr in County Offaly, the Seir Keiran Sheela was described in a 1834 Dublin Penny Review as a “grotesque figure” and illustrated as being on the eastern gable wall of the church.18 Later she was found against the bank of an earth wall of the enclosure which encompassed twenty-five acres of monastery ruins, a graveyard and a holy well about which “stories of miraculous happenings” are still told.19 An area rich in ancient traditions, once part of the old kingdom of Ossory, and according to the Shell Guide of Ireland, it may have been a pagan sanctuary.20 Currently, the figure is one of the few Sheelas on permanent display at the National Museum; one can readily understand the curator’s choice.

A formidable piece of sculpture, the strength of her massive shoulders and weight of her barrel chest give a rounded dimension to the figure. But as a visual image, the eye is first drawn to what makes this Sheela unique: the eleven holes or cupmarks sculpted into her torso. Eight round and square holes encircle her vulva in an irregular grouping that punctuates her wide display. Of the remaining marks, one pierces the base of her throat, and the other two rest on the crown of her head. There can be no architectural purpose for them, only a ritualistic one and certainly not for any recognizable Christian rite.

One can imagine the Seir Keiran Sheela decorated with the horns of the moon, with branches, flowers, or other such offerings. Perhaps the largest of the holes, just below her vulva, contained water with which worshipers could bless themselves. A cupmark is like a small holy well, gathering the life-giving moisture of the Goddess, her waters of life.21 Calling Seir Keiran the most pagan of all Sheelas, Andersen feels that “certainly, at some stage, there must have been people who believed in the power emanating from that image, some ritual must have centered on it.”22 For him, the image: “obviously involves significant beliefs of a past age…the only absolutely convincing fertility image among the Irish carvings…that air of potency, that aura of myth.”23

Whether there are still-living Sheela na gigs today practicing their art in the countryside of Ireland, one cannot say, but the display of the stone Sheelas persists as does a faith in the healing powers of the image. Certain folk customs live even now for “the restoration of health and protection against illness.”24 To obtain their good-luck stone dust, contemporary rubbings on the vulvas of the Kilsarkin, Castlemagner, and Clenagh Sheelas demonstrate that they continue to receive the caresses of their admirers to this day.

Starr Goode is currently writing a book titled Sheela na gig, Dark Goddess of Europe: In Pursuit of an Image to be published by Goddess Ink in 2013. Her previous work on the Sheelas has been published in Irish Journal of Feminist Studies, ReVision: A Journal of Consciousness and Transformation, and the three volume encyclopedia, Goddesses in World Culture.

Recent essay publications include, “In Praise of the Fool,” Word River Literary Review, Spring 2012, University of Nevada and “Falstaff and the Art of Living,” New Laurel Review, Volume XXV, 2012. She was the moderator for the cable TV series, The Goddess in Art, now housed in the permanent collection of the Getty Museum. She has been profiled for her work as a cultural commentator in the LA Weekly, the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal and The New Yorker. She teaches literature and writing at Santa Monica College.

Image Credit: Ruth Ann Anderson, from a photograph by Starr Goode

Notes

1. Margaret. A. Murray, “Female Fertility Figures,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 64 (1934): 93–100, and plates IX–XII, 99.

2. Edith Guest. “Ballyvourney and its Sheela-na-gig.” Folklore 48 (1937): 380.

3. James O’Connor, Sheela na gig (Fethard, County Tipperary: Fethard Historical Society, 1991), 11.

4. Barbara Freitag. Sheela-nag-gigs: Unravelling an Enigma (London: Routledge, 2004), 70.

5. Ibid., 70.

6. Ibid., 70.

7. Edith Guest. “Irish Sheela-na-gigs in 1935.” Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 66 (1936): 117; 110.

8. Guest, “Ballyvourney and its Sheela-na-gig,” 374-384.

9. Guest, “Irish Sheela-na-gigs in 1935,” 122.

10. Jorgen Andersen, The Witch on the Wall (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1977), 23. (Text translated from the German and Latin by Miriam Robbins Dexter.)

11. Ibid., 23.

12. Anthony Weir and James Jerman, Images of Lust: Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches (London: B. T. Batsford, 1986), 15.

13. Ibid., 15.

14. Guest, “Irish Sheela-na-gigs in 1935,” 127.

15. Ibid., 127.

16. Jorgen Andersen, The Witch on the Wall, 24.

17. Ibid., 24.

18. Guest, “Irish Sheela-na-gigs in 1935,” 114.

19. Guest, “Ballyvourney and its Sheela-na-gig,” 381.

20. Jorgen Andersen, The Witch on the Wall, 88.

21. Marija Gimbutas, The Language of the Goddess (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1989), 61.

22. Jorgen Andersen, The Witch on the Wall, 31.

23. Ibid., 87-91. 24. Eamonn P. Kelly, Sheela-na-gigs: Origins and Functions (Dublin: County House, 1996), 40.

Bibliography

Andersen, Jorgen. The Witch on the Wall. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1977.

Dexter, Miriam Robbins, and Starr Goode. “The Sheela na gigs, Sexuality, and the Goddess in Ancient Ireland.” Irish Journal of Feminist Studies 4, no. 2 (2002): 50–75.

Freitag, Barbara. Sheela-nag-gigs: Unravelling an Enigma. London: Routledge, 2004.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Language of the Goddess. San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1989.

Goode, Starr, and Miriam Robbins Dexter. “Sexuality, the Sheela na gigs, and the Goddess in Ancient Ireland.” ReVision 23, no. 1 (2000) 38–48.

Guest, Edith. “Ballyvourney and its Sheela-na-gig.” Folklore 48 (1937): 374–384.

Guest, Edith. “Irish Sheela-na-gigs in 1935.” Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 66 (1936): 107–129.

Kelly, Eamonn P. Sheela-na-gigs: Origins and Functions. Dublin: County House, 1996.

Murray, Margaret. A. “Female Fertility Figures.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 64 (1934): 93–100 and plates IX–XII.

O’Connor, James. Sheela na gig. Fethard, County Tipperary: Fethard Historical Society, 1991.

O’Donovan, John. Ordnance Survey Letters, Tipperary. Ms. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. 1840.

Weir, Anthony, and James Jerman. Images of Lust: Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches. London: B. T. Batsford, 1986.

©2026 Black Earth Institute. All rights reserved. | ISSN# 2327-784X | Site Admin