a literary journal published by the Black Earth Institute dedicated to re-forging the links between art and spirit, earth and society

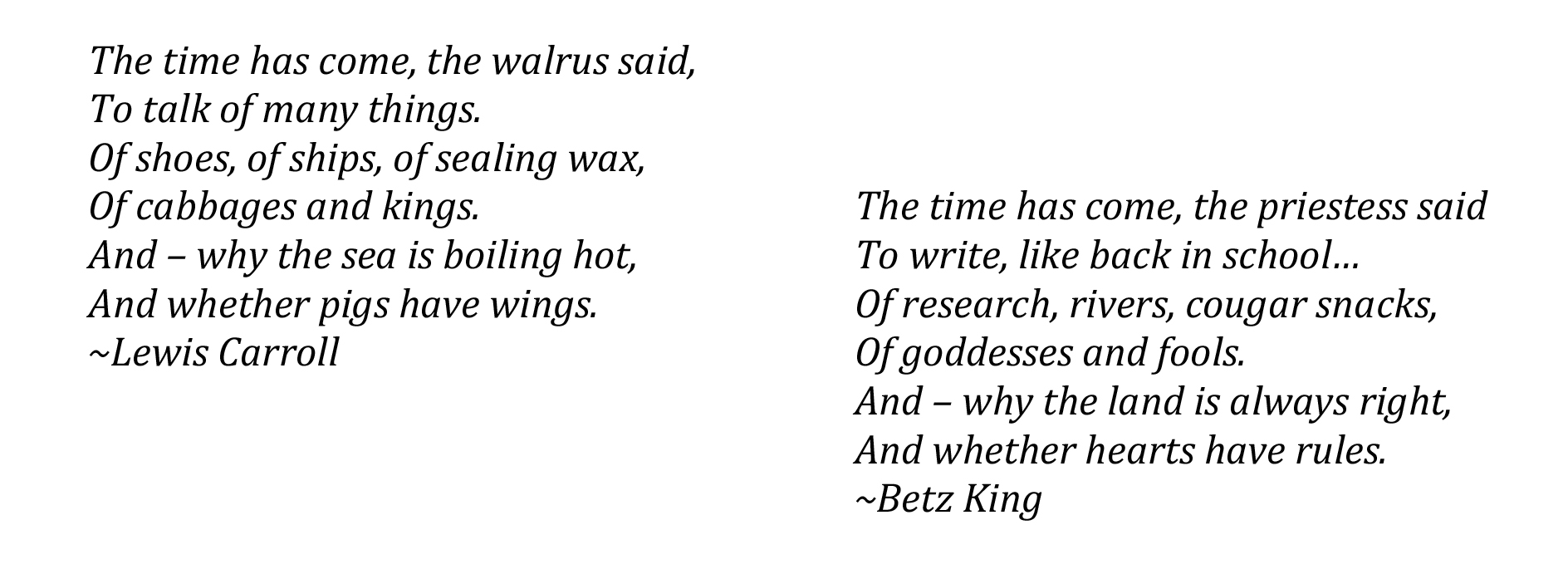

Of goddesses and fools

The places of earth, spirit and society first overlapped during my doctoral interview at the Center for Humanistic Studies in Detroit Michigan. Born in the zeitgeist of late ’50’s and early 60’s social justice movements, CHS was a critical midwife in the birth of humanistic psychology. Defecting from previous camps that viewed humans as a collection of unconscious impulses or learned behaviors, humanistic psychology posited that humans possessed an inherent desire to make meaning and to grow, and if treated with unconditional positive regard, would do just that. Rooted in existential concepts of freedom, personal responsibility, choice and authenticity, CHS was a magical program, held in a beautiful old house in the heart of Detroit’s cultural center. The library, complete with card catalog, was in a carriage house outback, and the school’s motto was “Trust the Process”. A bit like a Waldorf school for grown ups, experiential activities were valued above all other teaching methods and the class syllabi were ‘suggestions’ that could be wandered away from in favor of following one’s bliss (as long as one could explain one’s bliss adequately). I desperately wanted to get in.

The late Dr. Aombaye Ramsey led my interview. A Black civil rights activist who wore his tribal robes to class and taught his students to question an author’s motive whether reading cereal boxes or research articles, Aombaye was both daunting and comforting in the way that great leaders often are, mixing confidence and compassion with quite a bit of patience for the youngsters he found himself surrounded with. When he asked me why I wanted a doctoral degree in psychology, I forgot all of my eloquently rehearsed answers, and blurted out the clumsy truth: “The big dogs have all the power, and things need to change, so I wanna be one of the big dogs”. This in no way displayed my academic potential or my mastery of the English language. Big dogs? Things need to change? I was mortified. But Aombaye must’ve been listening between the lines (the way all good mentors do) because he let me in.

A couple of years later, I was trying to find ways to combine my work as a feminist psychologist and as a priestess of the Western Mystery Tradition. Find a dozen people who even know what all of those words mean and you’ll begin to understand that these feathers in my cap were rather specialized. It was out of this spiritual loneliness that my dissertation topic was born and I committed to researching women’s experiences of embodied spiritual empowerment. I wanted to find women who believed in the divine feminine while wearing their spirituality in their bodies, on the earth, holding all three sacred. Question was… could I find a dozen to interview, and could I find a mentor to oversee the project? Many rejection letters later, it didn’t look good. Detroit was not a destination that adjunct faculty clamor to visit, and 1st person narrative scholarship was still considered fringy in many places.

Then a friend gave me “The Goddess Path” for Solstice, and I noticed that the author, Patricia Monaghan, “welcomed correspondence.” After just a few short emails, she kindly agreed to help me qualify and defend my dissertation. My left of center humanistic psychology program, with its fondness for first-person narrative and qualitative research models was no mystery to her, it was a delight. I had myself a mentor.

My first challenge was to have Patricia approved as my adjunct professor when her PhD was not in psychology. Her own research combining chaos theory, quantum mechanics and poetry didn’t strike my committee as psychological enough. (Personally, I was thinking, “if psychology can’t tie these three things together, what can?”) Fortunately, she had also published prolifically on matters of feminist spirituality, and she hailed from a faculty position at DePaul University. Again, Aombaye Ramsey, in the tribal robes that made him look a bit more like a wizard than a psychologist, saved the day, arguing that a topic as specialized as mine required an adjunct with knowledge of writing and feminist spirituality. There would be, he reminded us, several psychologists at the table already. The vote went in my favor and we were green lighted to begin. Idealistically, I began imagining ways in which my research would bring the Goddess back into mainstream society, while abolishing women’s hatred of their bodies and improving their sex lives. When my research was ready to be proposed, Patricia declined a plane ticket from Chicago to Detroit, preferring to commune with the land while making the five hour drive, and we met for the first time.

Although CHS had since moved to a more modern facility, and the library was now inside the building, there was still enough magic to delight Patricia as she took the tour of the school and marveled at the rows and rows of heuristic theses and dissertations written by authors fully present in their research studies. She instantly fit right in.

Since I was researching embodied spirituality at CHS, I thought it entirely appropriate to embody the process with an experiential activity. I invited some priestess-colleagues to be consultants on my committee, which allowed them to attend my meeting. We each wore a colored stole representing an aspect of wisdom, and processed into the conference room, placing a flower in a vase on the table. And because I called it a ritual, it was. While the research was given the go ahead, the (rather tame, in my humble opinion) ritual was declared “inappropriate”, and resulted in a “no rituals at dissertation meetings rule”. Patricia found no shortage of humor in both my faux pas and the resulting rule. She’d long ago given up trying to locate the line between alternative and inappropriate, because, she said, “it keeps moving, and it’s never where you left it”. Chagrined that even in non-traditional academia I could wander into troubled waters so easily, I slinked off to find women who had “faith and sex and God in the belly” (thank you Counting Crows, I couldn’t have said it better), and Pat went back to Wisconsin.

As my research came to completion, the school began the process of applying for accreditation with the American Psychological Association. Some dyed-in-the-wool humanists likened this to ‘sleeping with the enemy’, as the APA and Humanistic Psychology rarely sat next to each other on the bus, but the Michigan Board of Psychology had passed a state law requiring all graduate schools to have APA accreditation by the year 2015. It wasn’t a matter of if we were joining; it was a matter of when. At the top of the to do list? A name change, to The Michigan School of Professional Psychology (MiSPP). Grades followed, in a school that had been grade-less for decades. New faculty were brought in, and syllabi full of juicy 70’s classics like “I’m ok you’re ok” and “The feminine mystique” were replaced by scholarly peer reviewed journal articles full of t-scores. Some welcomed the changes, others mourned. Given my philosophical belief that the big dogs have the power, and that things needed to change in the field of psychology, I wanted our school to become a big dog, so I embraced the tension of this transformation and scheduled my dissertation defense meeting so that it fell along side one of Patricia’s book signing tours. She would stop by on her way across the country and together we would prove beyond a reasonable doubt that I was an expert on my topic.

My research results revealed that women with an embodied sense of spiritual empowerment were transcending false polarities such as heaven vs. earth, body vs. spirit, and god vs. goddess. They understood the importance of working with like-minded individuals to transform the old patriarchal ways into even older more inclusive ways. At the dissertation defense, Patricia called the work “groundbreaking” in its importance. (I was just trying not to get in trouble again. Groundbreaking was the furthest thing from my mind). Once I’d successfully defended my dissertation, I played a song and told a story, and because I didn’t call it a ritual, it wasn’t. After a secret verbal handshake of “merry meet and merry part”, the women of my committee called me Dr King for the first time and my blood ran cold as I heard what they’d just said.

Doctor.

King.

That’s a PAIR of patriarchal titles! You might as well say Prince Duke, or Baron Von Emperor or Mister Man! In 35 years of education pursuits, it had never crossed my mind that when I completed my studies, I’d have the most patriarchal name on the planet as I worked to champion the divine feminine. I tried to comfort myself with images of the other activist named Dr. King (Martin Luther), and ordered a vanity plate that read “docking”. Imagine my delight when passers by perceived it as a reference to either “the mother ship” or a sail boat.

There was nothing to be done but to keep calm and carry on, so the priestess and feminist psychologist ironically known as Dr. King graduated, set up a private practice, and was shortly thereafter hired by The Michigan School of Professional Psychology.

Over the next few years I became more and more involved with administrative and curricular activities, eventually taking a position similar to that of a vice principle in public school. In other words, I became “the man”, enforcing “the rules”, the person that students feared to visit, the same person I had to visit after the aforementioned inappropriate ritual. I also began to make important decisions regarding the direction of the curriculum and the training of young therapists. My long ago intention to become one of the big dogs so that I could change things had come to fruition. This reminded me of Alice falling out of Wonderland rather than into it; as me and my pagan priestess, feminist psychologist, doubly patriarchal title became the spokeswoman of Tradition with a capital T (that rhymes with P, that stands for patriarchy). Curiouser and curiouser, as Alice would’ve said.

But I was ok, because I had a secret weapon. I had Patricia Monaghan on email speed dial.

Oh the sagas I sent her, lamenting, panicking, confessing… and oh the replies she sent back, commiserating, calming and validating. For she too was trying to legitimize feminist scholarship, champion the goddess and change the world within structures that ran contrary to her way of being in the world. Generously, she shared not only her hard learned wisdom, but her entire life. She invited me to be a Straw Boy in her wedding – a representative of the fool or trickster energy – and from this I learned several lewd dance moves and the importance of welcoming chaos into all creative pursuits. She invited me to Brigit Rest, inspiring my search for a piece of land I could call my own, and I found it – half a acre of wilderness in the middle of the city, resplendent with river and wildlife. She invited me to present and publish in projects she was involved in, and from this I learned that I use too many commas, and that I have a responsibility to use my voice to change the world, whether I feel competent or not. She helped me step on less toes, and laughed with me when I couldn’t avoid doing so. It made perfect sense to her that I was a pagan priestess psychologist professor, and because she embraced that vision of me, I walked around in it a bit more comfortably.

Years later, Patricia has moved to the Summerland and our email carriers are incompatible. Now if I want to connect with her, I wander out into my yard (barefoot) honor the river running through it (by the name it revealed to me), and check on my strawberries and sage. We have a cougar sharing the land and I fear for my wee puppies, the perfect cougar snacks. I fear for the cougar too, surrounded by the city and scapegoated by the villagers. This tension between earth, spirit and society, it’s even in my own back yard! So I do what any pagan priestess would do. I cast protection spells on my puppies, place cotton balls soaked in wolf urine along my property line, ask the neighbors to keep an eye out and surround the cougar with healing white light. There is no right and wrong; there is only what serves us and what doesn’t serve us. It serves me to advocate for the “and”, (puppies and cougars, gods and goddesses, rules and rituals) because the “either-or” has cost us all so much.

Academically, the quest for APA accreditation continues. We have done our part, and await notice of our fate. In the meantime, the APA has released its latest diagnostic bible, the DSM-5. Humanistic psychology is a strong voice of dissent regarding many of the proposed changes, and I am proud of my place in this movement. Standardized mental health, standardized education, they have a place. Sometimes I’ll be the representative of that place, because the big dogs have the power to change things, and things need to change. Sometimes I’ll challenge that place to be more inclusive and tolerant and just. And sometimes my heart will lead me out past the rules, to the wild places where the paradoxes of puppies, coyotes and priestess Dr. King all wade in the same ancient river and call it home. And because we call it home, it will be.

Betz King is a pagan (but not a Witch), priestess of the Western Mystery Tradition (without a temple), and champion of the divine feminine (who does not believe that the divine has a gender). She is also an existential psychologist who firmly believes that the “givens of existence” (death, isolation, freedom and meaninglessness) drive many an angst ridden seeker to lock down a belief system simply to secure an afterlife, companionship, boundaries and a mission statement. Betz teaches at The Michigan School of Professional Psychology in Farmington Hills Michigan, has a private practice specializing in women’s empowerment, and founded The American Priestess Training Program as a kick in the shins of organized religion. She shares her heart and home with her husband Kyle, three dogs, and a black cat. More info at: www.betzking.com

©2026 Black Earth Institute. All rights reserved. | ISSN# 2327-784X | Site Admin