a literary journal published by the Black Earth Institute dedicated to re-forging the links between art and spirit, earth and society

Mel Kenne

Phrygia / Remains

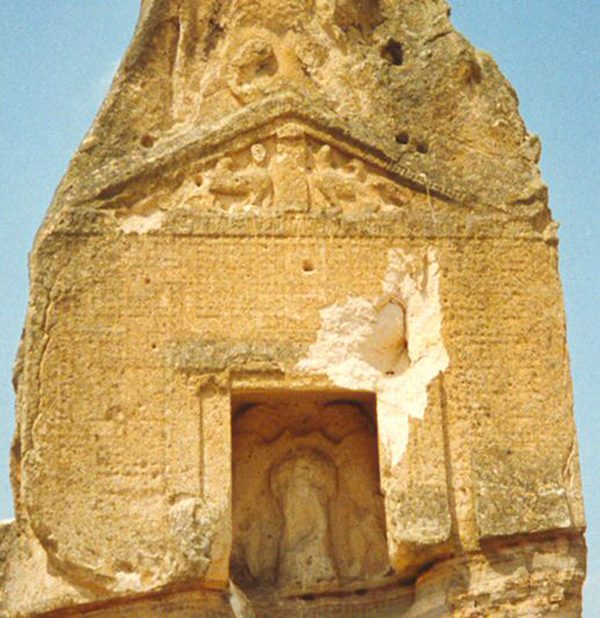

Lines for the Lion Goddess

Here’s what we saw

at Aizanoi:

a massive stone countenance

we stood before

and looked upon for

a long time,

as on some nameless

and inviolable law

that subsumed us with

the bright mask

of a green spring day

and sun burning down—

our faces left etched

by a closing claw.

Flanked by lions

rampant, her figure,

but she disfigured:

face chipped away,

elemental again: dust.

Now only a faint,

worn-down bust

framed by the posts

of a stone doorway.

Could it provide us

a way, a threshold

we might one day cross,

to attain sight of another,

more original stance,

a likeness equal to

the one long ago lost,

and bring light back

to despoiled immanence?

We may be reminded here

of stories we were told

of your furry ass’s ears

and baleful golden touch

that are not apparent now,

nowhere near this place

given over to centuries

full of wind-riven silence.

Not felt by us in this pure

light and air enclosing

sacred space where some

treasure more than fools’

gold must have once been

held dear, before it was

lost: stolen, profaned, or

just plain squandered.

Yet it seems to us that

another mystery must

have arisen here, a vision

that somehow got blurred

and was at last forgotten.

For now we can only see,

or imagine, from this

barren terrain, the sparse

evidence we survey, what’s

gone from shadow-filled

fissures scoring these

ochre and gray cliff walls,

and what’s left in this

late afternoon’s stillness

of golden light washed over

flaking volcanic ridges

and gaping cave mouths

whose burned-out interiors

defaced by looters now

only contain their own

stale air and silence.

Yet nothing spared, no

trace of an explanation

of what could’ve passed here

but that which remains

and lies before us as

the one certainty we face,

rendered exquisitely clear.

Yilantaş

The royal lion overthrown,

its head tipped upside-down,

and the uroboral snake,

broken down to segments

scattered among a heap

of huge boulders, remain

to be seen and turned over

again and again in our minds,

which seek some restoration,

or restitution, a way we can

make something more of these

ruins than they appear to be,

as they rise before us now.

As if by such reconstruction,

we could finally come to

some understanding of our

own time’s ghosts, our loss.

Like detectives who brood

over a pile of half-erased clues,

we lean above a bounty of

corpses collapsed long ago

to a film of white dust in

this litter of broken sarcophagi

and looted tombs. Nothing

you can really put your

finger on that’s not already

been clearly and officially

sealed by the stamp of doom.

*

Or do we only seek to

refill the gaps we now see

occupied by these cheerful

armies of picnicking families?

The adults gathered around

their small cooking fires,

seated upon faded kilims

covered by intricate webs

of red, blue and yellow ancestral

designs, woven into the rich

earth tones and fresh green

textures of their surroundings.

And the pure, liquid gaze

of children whose curious

stares hang not on the losses

of past centuries, but upon

these funny-faced foreigners

poking around, scrambling

over the stone blocks filling

their sunny playground.

Mel Kenne is the author of six books of poetry. His most recent collection, Take, was published in 2012 by Muse-Pie Press. In 2010 Yapi Kredi Publishers in Istanbul published a bilingual collection of his poetry, Galata’dan / The View from Galata, in Turkish and English. His second book, South Wind, won the 1984 Austin Book Award. In 2010 he was one of the Nazim Hikmet Poetry Award winners. He recently retired from the Kadir Has University Department of American Culture and Literature in Istanbul, Turkey, but he continues to live in the city that he feels is still the heart of the world.

©2026 Black Earth Institute. All rights reserved. | ISSN# 2327-784X | Site Admin