To be human is to be linguistically … enframed.

—Max Oelschlager

When you live in Wyoming, you feel the gravity of the National Parks. They tug on your attention. For the first decade that my wife and I lived in Casper, we spent our spare time together in Yellowstone. On route from our house to the northwest corner of the state, we drove along the edge of Green Mountain. Each time we passed its peaks, Lynn would say things like, “We should drive up there some day.” I would reply, “Yeah. I could fly fish.” Last summer, our responsibilities kept us from ranging too far away from home, but in July a free weekend showed up on the calendar. We packed our tent and drove to Green Mountain. I intended to fish the creek that runs from the high country to the plains at the base of the range. Lynn planned to pick sagebrush. She likes to wrap and bundle the branches.

* * * *

Two miles from the spot where we expect to stay, we notice a sign on the side of the road. In brown and white it says, “Cottonwood Campground—2 miles.” The next line says, “Wild Horse Point—10 miles.” The arrows lead in the same direction. We look at each other. Lynn says what we are both thinking, “Wild horses?” We pitch the tent beside Cottonwood Creek. Then we take a minute to open a couple of beers. It’s a tradition. We drink a brew when we christen a new campsite. We unfold our collapsible chairs and gather a bunch of firewood. I consider fishing, but the thought of wild horses keeps me off the stream. I ask Lynn, “Do you think there are mustangs on this mountain?” She says, “I don’t know. Let’s drive up and take a look.”

* * * *

It’s an uneven path that leads to the top of the range. It switchbacks through stands of limber pine to an elevation of 9,600 feet. At the top, the trees thin out. The road runs beside the rim of a ledge that offers a view of the Red Desert stretching toward the south. At the summit another sign directs us to the east. We plunk between ruts on the trail for a mile and then stop at a parking lot. Wild Horse Point hosts a picnic ground with a long view.

We store a pair of binoculars in the backseat of our car. We usually use them to look for owls, but this time we train the glass on a row of dots in the distance. They look like horses, but they’re too far off. I can’t tell. They could be cows. Still, it’s fun to stare into the panorama.

After we’re satisfied that there are no mustangs at Wild Horse Point, we climb back in the car. Instead of driving back to camp, we take a left on a road that winds through a meadow. Lynn admires the blue-green sage. I notice something, though. I see a patch of gold and white. It’s the back of a mustang. My instincts shoot my right foot to the brake pedal. The car lurches. Lynn says, “What?” so I point out through my window. Then we grab our cameras. We start to walk slowly, through the brush, toward the horse. He’s grazing in a gully. The sound of tires on gravel alerted him to our presence, so when we appear over the crest of the ridge he’s not surprised. He looks at us and then lowers his head. He nibbles at the grass. Beep. Click. Shutters open and close.

Once we’ve hiked enough to take a good look at the horse, we see that he’s not alone. He is standing in the shadow of four other mustangs—a band of bachelors—gray and black males spending the summer at the top of the mountain. They coordinate their grazing. Heads shift from side-to-side, between bunches of grass. We hedge up to the gold and white horse. We move closer. Then he takes a step to maintain his distance. Lynn and I notice, when he walks away, the others also readjust. They shift to separate themselves from him.

Lynn says, “He’s an outsider. They won’t let him join the group.”

I ask, “Do you want to loop around and try to move in closer to the bachelors?”

“No,” she answers. Then she says, “I want to stay with Ponyboy.”

He is the first mustang we named. Together, we’ve spent a long time observing and making photographs of animals. We had never named any of them. In Yellowstone, for example, grizzly bears each have a number. We used to search the Park looking for bear “399.” Numbers don’t lend themselves to narrative. It’s tough to build a meaningful story about a number. On the other hand, the name “Ponyboy” inspires our imaginations. We talk about the character by that name in the film The Outsiders, based on the book by S.E. Hinton. We wonder if the painted horse had been marginalized on account of his two-toned, gold and white coat. We ponder the question of whether horses can feel excluded. We start to build Ponyboy’s past. We begin to weave him a story. We cannot help ourselves. People are storytellers.

Other creatures engage the world by different means. Ospreys absorb the ground with their vision, for example. They interpret their habitat with their two eyes. Badgers live in dark and quiet haunts. They depend on their sense of touch—feeling their way through rocks and bones under the surface of the Earth. A grizzly bear can smell food four miles away, but we don’t work like that. During the course of human evolution our senses lost acuteness. We cannot see or smell or hear like other animals. Our senses provide our brains with a simple baseline of information. Upon that line, our minds go to work assembling words. We use words to give meaning to places and events. For example, when I look out my living room window onto my lawn, I see “dandelions.” The word defines my experience of the “weeds” in my front yard. “Dandelions” are “weeds.”

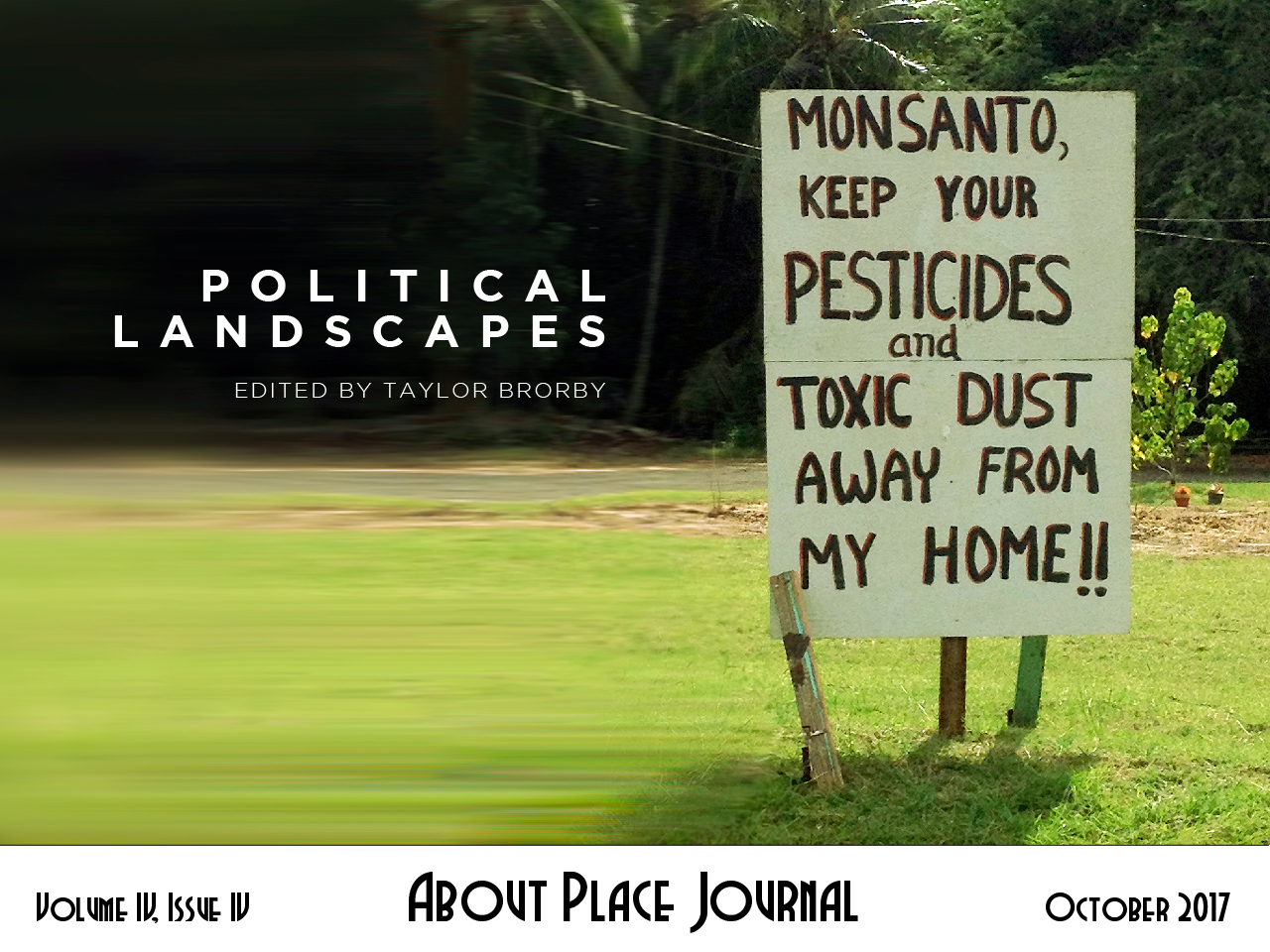

When you walk through the lawn “care” aisle of a hardware store you smell the herbicide. Pesticide. Mists and sprays and bags of granules. We must eradicate the weeds. If we fail, it becomes a commentary on our character. Dandelions in the yard serve as a sign—an indication of negligence. When homeowners allow dandelions onto the lawn it means that they don’t care about the value of their real estate. Worse, it could mean that they don’t care about the value of their neighbor’s property.

In some nations, when they speak of “values,” they invoke a set of principles. For some, values represent the standards that they work to live up to and embody. The Sioux value commitment to community. The Navajo value beauty in their lives and in the world. When Americans use the word “value” we rarely refer to standards or principles. More often, we use the term to refer to the cost of goods or services. Our tendency is to reduce our understanding of both our environment, and ourselves, to prices set in the market. For example, when our superiors set our annual salaries, they put a price tag on a year’s worth of our days. After work, we go home to our largest investments, or largest expenses, our homes. The story that we use to understand life is the story of economics.

It’s a potent story. When Americans made their way out of the eastern forests and onto the grasslands of the West, we found the largest mass of migrating mammals ever known: bison. We also found an array of plants and animals living in concert with the herds, a complement of flora and fauna more rich and diverse than any that we are aware of, historically. We didn’t see the western prairie as a miracle of nature, however. We saw parcels of real estate. We saw the soil as property and the grass as a means to grow commodities. Cattle, mostly. The narrative we used to explain what we found centered on finance. In our culture, we leave little room for moral and aesthetic considerations. We don’t dwell on questions of truth or rightness or beauty. Our story demands that we use “resources” to contribute to economic growth.

In the beginning, grizzly bears lived on the prairie. The marketplace does not value grizzlies. Plus, they are big and dangerous. We killed them first. Then we removed the wolves. Afterward, we turned a herd of 60 million bison into a group of 23 animals. We placed bounties on the heads of coyotes and mountain lions. We poisoned the prairie dog. When prairie dog towns disappeared, we lost the predators that depend on them: burrowing owls and black-footed ferrets. In short, we turned the wildest region on Earth—the Great Plains—into an enormous, one dimensional, mono-cultural, veal-fattening pen. We created “flyover country,” the geographical equivalent of a factory floor.

I know that we’re taught to picture trees and mountains when we picture “wilderness.” The official wilderness areas protected by the government contain either forests or mountain peaks. I’ve visited many of the wilderness areas in the West. The weather is wild. Straight-line winds tear at the fabric of tents. Sometimes it sounds like you’re stuck in the same room as lightning. Most animals know better than to dwell in places covered by snow for a large part of the year, however. Our wilderness areas are pretty, but the land is often barren. Wilderness areas rarely provide homes for large or diverse collections of animals. Some wilderness areas consist solely of rock and ice. Rock and ice possess no economic value, so when politicians went to designate wild places, “untrammeled by man,” they had the tops of mountain ranges to choose from. Since we found ways to make money on grasslands, we trammeled them thoroughly, but in the past, prairies were ferocious. The Great Plains were the wildest places on the planet.

* * * *

Not long after Lynn and I discovered that there were wild horses in Wyoming, we learned that the term “wild” is not universally used to describe them. In Wyoming, and other states with herds of mustangs, organized groups are fighting to remove the word “wild,” from conversations about horses. In particular, agribusiness people who graze cattle on public land want the term “wild” removed from our vocabulary. They prefer the word “feral.” In English, we define the terms similarly. Synonyms for both include: savage, untamed, and undomesticated. But the connotations of the words differ. We use “wild” to suggest a state of freedom and originality. In contrast, we use the term “feral” to describe domestic animals that have escaped.

The term “wild” conjures romantic feelings in our culture. When we see wild animals through the windows of our cars, we’re often thrilled. We’ll pull off of a road and stop to admire a wild animal. We take photographs and post them on the Internet. As a resident of Wyoming, I can attest: people travel for thousands of miles to drive the roads of my home state, just for the chance to maybe see something wild. The term feral does not move us that way. We don’t plan summer vacations around feral animals. With regard to the feral—we feel disdain.

Animals are animals. Even so, some we like and some we don’t. We take naps with some of them on the couch. Some we butcher and eat. We love German shepherds, but we built a Federal office with the charge of trapping, poisoning, and blowing up the dens of coyotes. We snuggle with huskies, but in most of Wyoming, anyone can shoot a wolf on sight. Scholars have only recently begun to give attention to the significance that we attach to animals. In contrast, social scientists have spent years giving thought to the ways that we treat each other. Sociologists have spent a century trying to understand the relationships among groups of people. Among those who study groups, the work of Gordon Allport stands out as distinctive. In his book, The Nature of Prejudice, he describes the processes that lead to bigotry.

Allport suggests that our first contact with a group can color our attitudes toward them for generations. His theory hinges on the power or status of groups when they contact one another for the first time. Allport’s model predicts that two groups will enjoy respectful relations when their first contact occurs at a time when they are equal. On the other hand, when groups of unequal status meet, the contact results in racism, or a scenario where the dominant group fails to accept the humanity of the other. Of course, such views provide the make-believe justification for wars, colonialism, and even enslavement.

When we see horses for the first time, it is nearly always in the context of a domestic setting. They pull our carts, buggies, and handsome cabs. We watch them run on tracks. Sometimes we ride on them ourselves. We come to know horses as property, although most of us will never possess the land or resources needed to keep them. For many in the West, however, particularly those who own horses, free roaming mustangs represent a threat to the established order. Westerners often see wild horses as having moved up beyond their station. This point of view can breed contempt. Many in the West look at mustangs with the same sort of condescension that we used to reserve for runaway slaves in colonial America.

It should come as no surprise to find stock growers working to change the way we talk about wild horses. The word “feral” reduces the romanticism and admiration that we feel toward the animals. From the standpoint of those who use our public lands for their personal businesses, the foals of wild horses appear on the prairie as weeds. In their minds, mustangs deserve the same kind of disrespect that we apply to dandelions sprouting uninvited on suburban lawns. The wild horses that roam free in the West have never known owners or domesticity. Even so, lobbyists for agribusinesses have begun a campaign to define the American mustang as a “feral” animal. If they succeed, it is conceivable that horses would suffer the same fate that we prescribe for other animals that we refer to as feral: poison, traps, and bullets.

* * * *

Agribusiness people have an economic agenda. They look at the prairies of the West through a lens shaped by the workings of the marketplace. When it comes to our prairie grasses, they see “animal-units-per-month,” or the number of cows that a parcel can feed. The language of economics animates the stories that we tell about the western states. The market that provides us with goods and services shapes our worldview to such a degree, the practice of reducing everything to economics can feel inevitable.

But within the scope of history, the market-based approach to life is relatively new. Historically, human beings tempered the judgments that take place in the market with mythology. In the past, we used myths to provide members of society with lessons, ethics, morals, and aesthetic preferences. Cultural narratives offered a way for human beings to reduce the intensity of our obsession with economics. Stories and legends allowed people to sidestep concerns about what is profitable in order to focus on questions like, “How should we live?” or “What is a good life?”

* * * *

During the time of their empire, Greeks found so much meaning in horses that they began to imagine a race of creatures that combined the body of a horse with the torso of a man: the centaur. Greeks valued the freedom of wild horses. Observing the creatures no doubt gave them a reason to consider the contrast between the autonomy of the beasts and their overly kempt cities. Centaurs possessed the traits of both horse and man, but their nature leaned toward that of the animal. In Greek mythology, centaurs appear feisty and spirited. That is, with one exception—the centaur Chiron—brother to Zeus and the tutor of Achilles. For the Greeks, Chiron represented patience, skill, and kindness. He served as a model for the group that would later become physicians. Myths serve the function of helping people to entertain the promise of a better world. For ages horses have been a part of that promise.

As societies like ours evolved, we used the science story to banish our myths. Even so, for most of American history, horse narratives gave us meaning. We’ve used horses as characters to help us define who we are, but we’re two generations removed from My Friend Flicka and The Black Stallion. The romance waned. We are at a point where we use cold calculations to provide the rationale for removing wild horses from public land. We’re left with the hollow characterization of the prairie as a commercial landscape. It can feel like we are caught in a Greek tragedy. In the production of a tragedy, a principle is set in motion. Then the principle plays itself out—all the way out—despite the efforts of those who understand the plot is sad.

* * * *

When my wife and I set out to look for mustangs we meet like-minded people. We’ve met photographers and naturalists. Horse owners and horse lovers. Outdoor enthusiasts of different stripes. We’re all interested in one thing. We want a glimpse of something big and beautiful. We want to look at, and thus become a part of, something that is still untamed. At home, we are welders, accountants, teachers, salespeople, and librarians. Day-to-day, our lives are more or less prescribed by the scripts embedded in our culture. Work … followed by a little bit of television … followed by sleep. Repeat. It’s the occasions that we have for recreation that allow us to craft the stories we need to define ourselves against the mundane aspects of our economic lives.

When you break the word “recreation” down to unlock its original meaning, you find: “re-creation.” Human beings use recreational outings to re-create themselves. We fashion a different version of ourselves when we take time away from our roles at work or home. Recreation allows us to become multi-dimensional. Leisure offers us a chance to set our feelings free.

* * * *

Lynn and I watched Ponyboy, off and on, for seven months. He stayed at the margins. We’d find him eating grass twenty feet from a group of bachelor stallions. Then, one day, we found the group that he tended to lurk near, but no Ponyboy. Through the winter, and into spring, Lynn and I would ask each other, “Where is Pony?” It became a meme. Now, it’s been more than a year since we’ve seen the gold and white horse, but we still ask each other, “Where is Ponyboy?” It makes me wonder where he went. I also wonder how many other people knew the horse. It makes me curious about the names they might have given to him. The last time we saw Pony, he had grown accustomed to cars on the road through his favorite meadow. He might have a thousand other names.

* * * *

Much has been written about the Adopt-a-Mustang program sponsored by the Bureau of Land Management. It’s a good program. Or, at least, a necessary one. Adoption is a better fate than a glue factory for horses that threaten to eat the grass that we would rather feed to cattle. Government agents round up the horses that they find. Then they offer them to potential owners, for a modest charge. Of course, in the arrangement, wild horses become property. They are broken. Although, we like to say that they are “trained.”

Mustang trainers will repeat a horse’s name until the animals develop new identities. Horses are smart. You don’t have to echo their names too often before they start to recognize them. Knowing one’s name is the first step toward taking on all of the obligations that go along with being somebody. “Buttercup,” for example. If you can get a horse to accept the name, that is the first step toward getting them to fulfill the responsibilities involved in being Buttercup.

Buttercup stands quietly in her stall.

Buttercup walks into the barn to eat her grain.

Etc.

Having a name is like having a job. Ponyboy may have a thousand names, but the lucky horse does not know one of them.

* * * *

Lynn and I keep planning new trips into the sagebrush. Part of me hopes that we find Ponyboy. There is also part of me that hopes he’s hiding somewhere in a valley or a canyon, out of reach—far from tourists and government officials. Near the end of the film The Outsiders, the character Johnny says something to the namesake of the horse that we met at the top of Green Mountain. He borrows a line from a poem by Robert Frost. He whispers, “Stay gold, Ponyboy. Stay gold.”