What stays: the cases of bottled water on the front porches and library steps. The sign by the Hoosic River, warning people not to swim. When you cross the bridge over the river just to get a better look, you spot three young men in the water, splashing around despite the sign.

Of course they are, you want to say to no one in particular. But then, it’s hot and humid out, and what else are they supposed to do in a tiny town like this?

You watch one of them walk gingerly over the cobbled bank, back to the phone tucked into his socks and shoes. He’s laughing. Wet shorts hang from his too-thin body, dripping water onto rocks and sand. He runs fingers through wet hair, and you wonder: does he not understand what’s in the water, or does he just not care?

The river glistens in the sunlight, its banks grown wild with vegetation. Heavy limbs reach low over silent railroad tracks; the chain-linked fence beside them choked with honeysuckle vine.

*

It smells green here. Not the freshly-cut-lawns of the suburbs, but softer and sweeter, like clover. Like green given time and permission to grow, like hay before the harvest. Or those summer mornings as a kid when you walked around barefoot in the dew and the sun had warmed the air just enough to awaken the bees, making you stop and look before taking another step. That’s what it smells like here.

French explorer Samuel de Champlain called this place Verd Mont, meaning “green mountain,” for the forested peaks of this little state. On my drive down from Middlebury, I watched the blue of distant ridges grow and sharpen into green.

The landscape is a time capsule. Unfettered views. Centuries-old buildings. Stone remnants of grist and textile mills tucked into hillsides with roaring creeks. Military forts and other relics of the Revolutionary War. In the summer, black and white Holsteins dot the horizon, grazing over long, lush pastures. Immaculate clouds gather above, casting shadows over felted hills. Clusters of white and yellow flowers crochet themselves into delicate lace along the road. Red barns and sugar houses lean in varied stages of decay, while roadside stands announce: Vermont Maple Syrup Here.

If you stop, you’ll be seduced. Sugar on the lips and tongue, and the soft air carries the sweet-heart call of a black-capped chickadee.

*

I’ve come down to Pownal because there are reports of Teflon in the drinking water. PFOA specifically (short for perfluorooctanoic acid), a toxic industrial chemical that was once used to make high performance plastics, like Gore-Tex, Teflon, and Teflon-treated products. Things like nonstick cookware, wax-coated food packaging material, insulated wiring, and water and stain-resistant fabrics, among hundreds of other goods.

PFOA is persistant, with its eight-carbon-chained backbone intentionally configured to resist chemical decay. It’s unnaturally stable, the key ingredient for chemical coatings that defied the rules of wear and tear. It’s the sort of compound that can transform fabric into something so impenetrable that astronauts in the Apollo Program wore it on their missions in outer space.

But the magic wasn’t strong enough to make the chemical disappear. PFOA collects in the elements of our environment without breaking down — in soil and water and sediment, weaving its way into the tissues of creatures that intersect its path. It accumulates in the blood of exposed people, residing inside their bodies for an average of 3.8 years before half of the absorbed material is even able to depart.

And it doesn’t leave without leaving its mark. The compound has been implicated in a number of health conditions, including ulcerative colitis, high cholesterol, immune system abnormalities, thyroid disease, effects on pregnancy and fetal development, liver damage, and cancer. And though it’s no longer manufactured in the United States, PFOA is so ubiquitous in the marketplace that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that most U.S. citizens have trace concentrations of the chemical in their blood just from the products they have used.

I’ve come down to Pownal because there are reports of Teflon in the drinking water. I’ve come because my husband’s coworker grew up here and is worried about her mother’s well. I’ve come because my husband told her that this is what I used to do.

*

I had worked as an environmental regulator in another state, in the remediation section of the department. Our group oversaw the investigation and remediation of contaminated sites, our mission was to protect human health and the environment from the effects of toxic releases. We were like the custodial police of the commercial and industrial sector, responding to leaks and spills, mobilizing field equipment and initiating enforcement actions so that no one would get hurt.

We put environmental laws into motion, our work guided by the lists of regulated contaminants and their respective exposure criteria — risk-based standards that were grounded in the difficult science of cause and (the likelihood of) effect. Those standards became our Bible. They helped us evaluate when corrective action was needed, and when remediation was complete. When I sampled someone’s drinking water well, for instance, because I was worried about some nearby solvent plume, I relied upon those standards to determine whether I could give the homeowners a green light to use their well.

Green implying permission. Green as in safe, green as in “clean.”

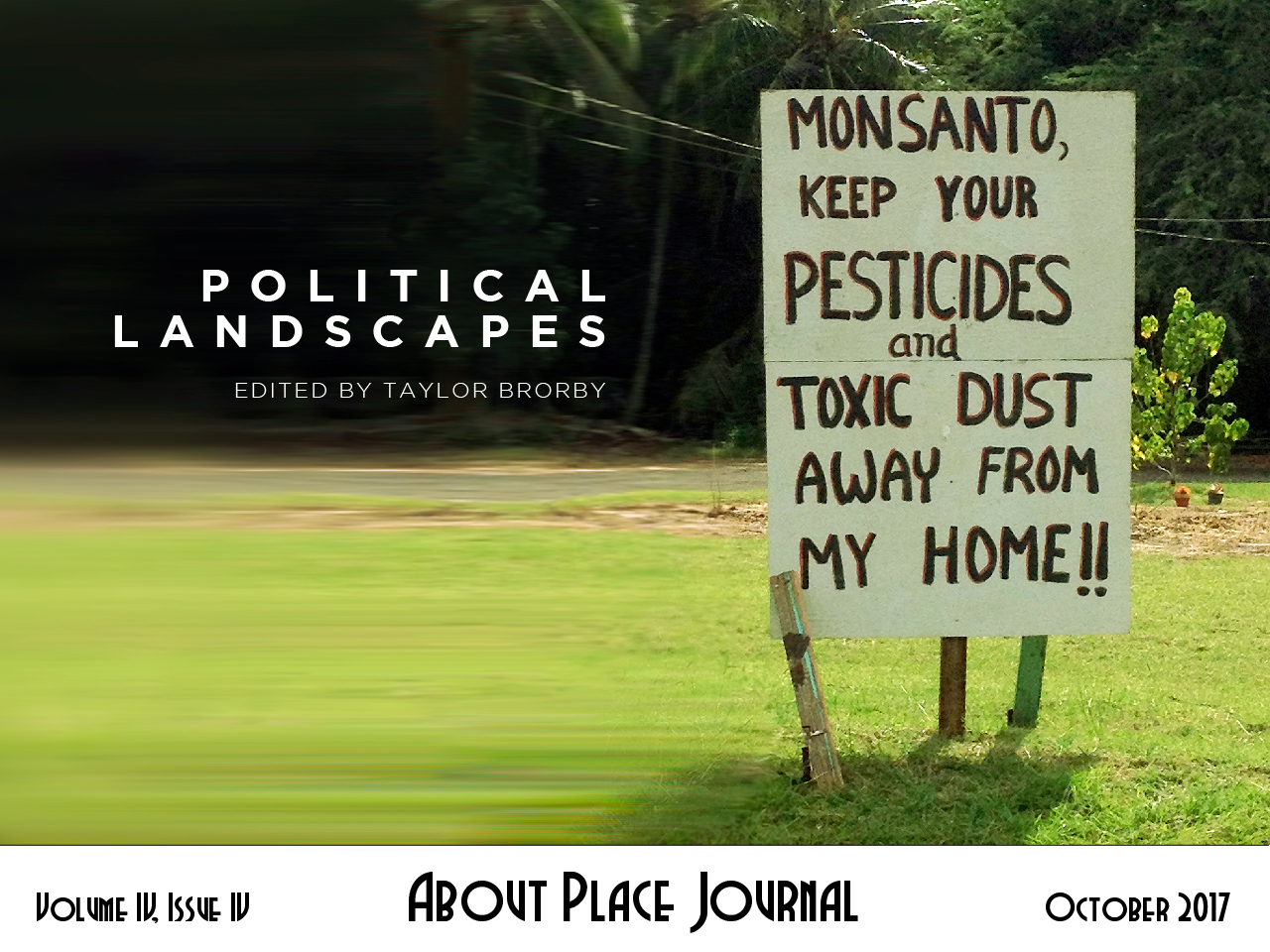

But PFOA was not a chemical that could be found on any regulatory lists. DuPont had made sure of that. Investigative reporting has since revealed that the company intentionally withheld information from the federal government and even its own workers about the health hazards of chronic exposure to PFOA. Turns out they were making too much money from Teflon to expose themselves to that kind of liability risk.

—Which meant that, for decades, PFOA flowed unregulated from the outfalls of companies manufacturing Teflon-treated goods into the curves of local rivers. For decades, PFOA was discharged through smokestacks and soared over green valleys, settling down into the crevices of land —like some invisible synthetic pollen— before catching a ride with precipitation to replenish drinking water resources. And while all of this was happening, local water sanitation workers dutifully sampled their community systems and analyzed the water for contaminants that didn’t include PFOA.

*

If you’re traveling here from the Berkshires of western Massachusetts, or from New York City and other urban areas of the Hudson River Valley, Pownal is likely your first taste of Vermont. The town occupies the southwestern corner of the state, nestled in the Hoosic River Valley between the wooded ridges of the Taconic and Green Mountain ranges. The terrain is exactly what you would expect: Green mountains all around. Large patches of fertile farmland stitched together with thin corridors of trees. A peaceful drive interrupted by an occasional gas station, a flea market building, a local beer and wine shop. Even the Green Mountain Racetrack has been converted to a solar farm. And the billboards fall away as soon as you cross the state line, because the rules in Vermont prohibit that sort of thing. We want nothing to distract you from the wholesome-ness of this place.

At first glance, Bennington County, Vermont is not a place where you would expect to find this kind of problem. You might find it in the heavily industrialized areas of Massachusetts and New York — or urban New Jersey, where Teflon was initially conceived. You might find such contamination in the “Chemical Valley” of southern Ohio and West Virginia along the banks of the weary Ohio River, where DuPont manufactured Teflon for more than 40 years. You wouldn’t think to look for it here. You expect to find such things in the places people are trying to escape when they vacation in Vermont.

But in between the mountains and ski resorts, farms, sugar houses, and quaint New England towns, there is a Vermont with a history that isn’t featured in the shiny brochures. A Vermont that —once you take a closer look— might seem a little less perfect, a little more like everywhere else.

*

I stand on the Furlong Road bridge over the Hoosic River in Pownal, watching the young men splashing around in water with tainted sediment. Beyond them, upstream, is a dam that used to power a facility that is no longer there. On the other side of the bridge, a road dead-ends into a fence with a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-issued No Trespassing sign. And along the river bank, I find a nice stretch of grass with park benches and shady trees, an American flag and an historic plaque in the location where the North Pownal Manufacturing Company used to stand.

The North Pownal Manufacturing Company was built in 1866 and operated as a cotton mill until 1936, when the Pownal Tanning Company took control. The tannery operated at the site until the company’s bankruptcy in 1988, leaving a vacant century-old building, a tannery sludge landfill, and heavy metal-laden wastewater lagoons along the banks of the Hoosic River.

The site sat unattended for roughly a decade before concern about the uncontrolled releases of solvents, metals, PCBs, and other notorious toxins rose to the top of the EPA’s agenda. The building was eventually demolished and the hazardous waste impoundments capped and covered under the federal Superfund program, creating this very recreational park and a new wastewater treatment facility for the community. That was over ten years ago, and warnings about swimming in this part of the Hoosic River still remain.

The park’s historic plaque displays pictures of the industrial property through time, including the original cotton mill alongside an iconic photo of a young girl named Addie Card — the “anemic little spinner” photographed by Lewis Hine in 1910, for the National Child Labor Committee. Gaunt eyes, skinny limbs, filthy smock. A twelve-year-old girl, a full-time employee, a victim of the Industrial Revolution.

It strikes me suddenly that Pownal is no stranger to the trauma of toxicity in one form or another. Pollution is perennial. Generation after generation bearing the burden of corporate wealth.

*

“What was it like to grow up down there?” I had asked my husband’s coworker over lunch before I took the trip. She told me all about about living in Pownal in the 1970s and 80s, how everyone looked out for everyone else. How, when she was a kid, the town was mostly teachers and police officers, secretaries and tannery workers. Double-income households and latchkey kids, except no locks on the doors.

“Where did you get your water?” I asked.

“We had two lines,” she said. “We had our own tap and we had tannery water.”

“Tannery water?”

She nodded. “We weren’t allowed to drink it. We used that to water the animals and the garden.”

I shifted in my seat, uncomfortable with the possibilities of what that really meant.

“When it rained a lot, the tannery water would get dark and cloudy.” She glanced at the plastic twelve-ounce container of iced tea I was holding in my hand. “Like that,” she said.

*

I park my car in the vacant Mack Molding facility, formerly Warren Wire Manufacturing — the presumed source of PFOA contamination in Pownal’s public water supply, and what was one of last remaining employers in this town. At the entrance of the parking lot, near a faded sign overgrown with weeds, two preteen boys are circling each other on their bikes. My presence seems to have thrown them, perhaps making them pause, wonder if maybe they shouldn’t be here after all. I’m wondering the same thing myself, my American ethic regarding private property so ingrained that it almost eclipses my right-to-know.

One of the boys raises his hand in a reluctant wave, testing me. I wave back, which somehow gives them permission to proceed. They ride by quickly, trespassing out of curiosity, perhaps, or just to get to the other side. I like to think my reasons are more principled than that.

Muscle memory leads me to the usual suspects: the loading dock, and what I assume to be part of the main production floor. It’s only after I’ve peeked in windows that I notice the sign warning me that video surveillance is in use. A witness to my witnessing.

The site investigation has already begun: I find at least one monitoring well, and the asphalt is freshly crumbled from Geoprobe borings recently completed around the building. I’m careful not to go too far, not to snoop too much, but I have a pretty good hunch about what they’ll find. The contaminated supply well, which serves roughly 450 people in Pownal’s Fire District #2, is close by. Too close, I think — only 1,000 feet away.

One thousand feet. Roughly the distance of a soapbox derby, something else whose outcome appears to depend on gravity and luck. Or a solid drive by a golfing pro. I realize now, that the distance between the presumed source of PFOA contamination and the water supply well for this town is shorter than a fairway — less than the distance from the tee box to its velvet putting green.

*

But Pownal isn’t a golf resort or country club kind of place. You’re more likely to find that in Bennington, a little further north, with its lovely downtown, its fancy liberal arts college and little restaurants and boutiques. Not that living in Bennington, or even near Bennington College would reduce your potential exposure to PFOA — but I’m getting ahead of myself.

*

Pownal isn’t the only place in the area with PFOA in the drinking water. It was first discovered across the state line in Hoosick Falls, New York — another historic rural community established further downstream on the banks of the Hoosic River, about a twenty-minute drive west from here. It started in 2014, when a man named Michael Hickey wondered about the connection between his father’s terminal kidney cancer and the Teflon ingredients his father had handled during his employment at Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics. Turns out the facility where Hickey’s father had worked for most of his life is located less than 500 yards from the water supply wells for the Village of Hoosick Falls.

When Hickey shared his concerns with village officials and asked them to test the water for PFOA, he was told that it was an unregulated compound, and that they were already in compliance with state and federal drinking water regulations. So he sampled the water from his kitchen tap and a few other sources around the village and paid for the analyses himself.

The results showed that Hickey’s water had 540 parts per trillion of PFOA, exceeding the EPA’s then non-enforceable guidance level of 400 ppt for short-term exposure. Clearly the water wasn’t safe, even though at the time, it officially met the requirements of state and federal drinking water rules.

Hickey’s findings went public in December 2015 and sent the Village of Hoosick Falls into a tailspin. Roughly 3,500 people had been unknowingly exposed to PFOA for an undetermined amount of time. The case received national attention and created a ripple effect in the region, particularly for all the other former-mill-towns-turned-Teflon-industry towns in these quiet forested hills. People across the border in Vermont wondered: If PFOA got into their water, could it be in our water, too?

Vermont officials conducted a statewide survey to identify all manufacturing facilities that had ever used PFOA, then sampled all public drinking water systems and private residential wells located in close proximity to identified sources. Their efforts revealed widespread PFOA contamination in residential wells located near the former ChemFab specialty fabrics plants in Bennington and North Bennington, as well as the public water system in Pownal Fire District #2. Residents were given bottled water, invited to have their blood serum tested, and assured that a long-term solution was in the works. And all the while, environmental health officials from the EPA and the states of New York and Vermont couldn’t seem to agree on what concentration of PFOA might be considered “safe.”

*

I can remember stepping over cases of bottled water to sample people’s residential wells and sympathizing with the families who found themselves in the path of a contaminant plume. I can recall navigating difficult homeowner questions about whether I thought their ailments could have been caused by the water they drank. And I remember having to explain the science behind risk-based exposure criteria to assure them that the regulatory standards were protective.

But I never had to answer questions about what it means to have a blood PFOA level of 250 micrograms per liter, and what that means for someone’s future. I never had to advise a mother on whether she should breastfeed her baby after she’d been exposed to a chemical for which we had no official safety standard. I never had to admit how little we know about a contaminant’s behavior in the environment, or its impact on our bodies, and how inexperienced we really are in protecting them from the chemicals we have no authority to oversee.

I never had to admit my terrible naïveté.

*

Questions that have been asked of Vermont officials on matters concerning PFOA contamination:

How big is the area of interest? Should I get my well tested? How do I get my well tested? What is the standard for PFOA? Why is the standard different in New York? Should I get my blood tested? What does my PFOA blood level mean? Will I get cancer? What about my child? How will this affect my child’s growth and development? Where do I get free bottled water? What do I do with my empty water jugs? What is a point-of-entry treatment system? How does it remove PFOA? How do I know that it’s working? Is a point-of-entry treatment system an acceptable long-term solution for removing PFOA contamination? What if my well has a concentration of PFOA that is lower than the standard? Will that change? Can I be connected to public water? When will construction of water line extensions begin? Is the public water safe to drink? Was PFOA disposed in the landfill? What additional environmental investigations are needed? Will the company responsible for the contamination continue to test the wells? How can I trust the results of sampling data collected by the responsible party? What about the soils? How deep will soil samples be collected? What about fish in the Hoosic and Walloomsac Rivers? Are those safe to eat? What about my garden? Is it okay to eat vegetables from my garden this year? What about maple syrup? Has the maple syrup been tested for PFOA?

*

I am relieved to see that my friend’s mother who lives in Pownal lives well beyond the PFOA contamination area of concern. And I suppose I could have figured that out with the aid of Google Maps and a little internet research from the comfort of my own home. But maybe there’s a part of me that misses this work a little bit — a part of me that wants to drive by the homes with bottled water on their steps, see those backyard gardens with their wind chimes and tomato vines to remember the important human element of the regulatory work I used to do. Or perhaps I want to remind myself that if something like this can happen here, it’s bound to happen anywhere.

Or maybe I just want to know the messy details of this place because it’ll make me feel more like a local in this adopted state of mine. Like now I might know the real Vermont, the one hidden behind the window dressing, and not just the one being marketed in the Welcome Center brochures.

*

My ten-year-old daughter recently completed a unit in school about the history of the state. She spent two weeks compiling information and constructing a poster to illustrate and explain all the interesting facts about Vermont: the state motto (Freedom and Unity), the state nickname (The Green Mountain State), the state bird (Hermit thrush), the state tree (Maple, obviously), the meaning of the symbols on the state flag, etcetera. At the end of their poster presentations, she and her classmates gathered at the front of the room together to sing the state song, “These Green Mountains.” They squirmed and avoided eye contact with the smiling parents seated before them, fidgeting with the edges of bitten fingernails and stretched-out sleeves. But they sang. They sang loud and strong:

These Green Mountains

These green hills and silver waters

are my home. They belong to me.

And to all of her sons and daughters

May they be strong and forever free.

Let us live to protect her beauty

And look with pride to the golden dome.

They say home is where the heart is

These green mountains are my home.

*

Green is youthful budding beauty wild vegetation leaves on trees and forested hills. Green is the Emerald City in the Land of Oz. Green is life. Green is peace. Green is pride. Green Mountains, green energy, green space. Green is the identity of this place. Green is its brand.

But green is a complicated color, a word with an entire spectrum of meaning. It’s one of those words that can mean youth and nature and life, but can also deliver hues that conjure illness or sickness. Or a jaded attitude.

*

When we first moved to Vermont, I couldn’t take my eyes off the views of Lake Champlain. Every time we ventured north toward Burlington, I would nearly drive into oncoming traffic as my eyes and attention drifted out over the open blue. After nine years living in the gnarled juniper and sage-filled high desert of Central Oregon, the gentle hue of the lake and its layers of lush, mountainous shores felt to me like the embodiment of abundance. Here was the land of milk and honey, where we would savor berries and homegrown greens with our local wine and cheese, all sourced directly from the Garden of Eden itself.

But we had moved in August, and the allure of the shore revealed that, indeed, the rain that falls upon those picturesque farms and dairies weaves its way through soil fertilized with liquid manure, gathering nutrients intended for crops and delivering them instead to the lapping waters of Lake Champlain. The whorls of algae floating near my toes unsettled me, and for a moment felt like glimpses of my childhood near the troubled Lake Erie shore.

I awakened then from my romantic reverie about my new home — which is not to say that I loved it any less. Perhaps I even loved it a little more, this water hurting for attention. It’s a rather compelling story, really. Water so starved for love, and so vulnerable to jealousy that it would assume the hue of the mountains that everyone’s always talking about.