Many artists today claim their work is hybrid or multidisciplinary or so multidimensional that it defies traditional classification, but artist Dao Strom truly fits that description. A poet. A memoirist. A novelist. A composer. A musician. A performer. A visual artist. An historian. A storyteller. She weaves and stretches the limits of every form she touches, never allowing complacency on the part of the viewer or herself. Dao Strom is a deep thinker at a time when everything feels like it is reactionary lightning. Although we live in the same town of Portland, Oregon, I’ve never had a chance to really talk with her. When this conversation took place, she was in Vietnam, the place of her birth, working on a project. She graciously agreed to answer my questions even as she was traveling.

Many artists today claim their work is hybrid or multidisciplinary or so multidimensional that it defies traditional classification, but artist Dao Strom truly fits that description. A poet. A memoirist. A novelist. A composer. A musician. A performer. A visual artist. An historian. A storyteller. She weaves and stretches the limits of every form she touches, never allowing complacency on the part of the viewer or herself. Dao Strom is a deep thinker at a time when everything feels like it is reactionary lightning. Although we live in the same town of Portland, Oregon, I’ve never had a chance to really talk with her. When this conversation took place, she was in Vietnam, the place of her birth, working on a project. She graciously agreed to answer my questions even as she was traveling.

Claudia Saleeby Savage: I watched “Traveler’s Ode” in Poetry Northwest and felt incredible grief. It is not just the white dress you wore; it is the way you fade in and out, the spaciousness of the poem, the spaciousness of your voice and the structure you occupy. The metaphors layer and echo each other. This feels thematic and contributes to the power of your work. Can you speak about this desire for echoing and layering?

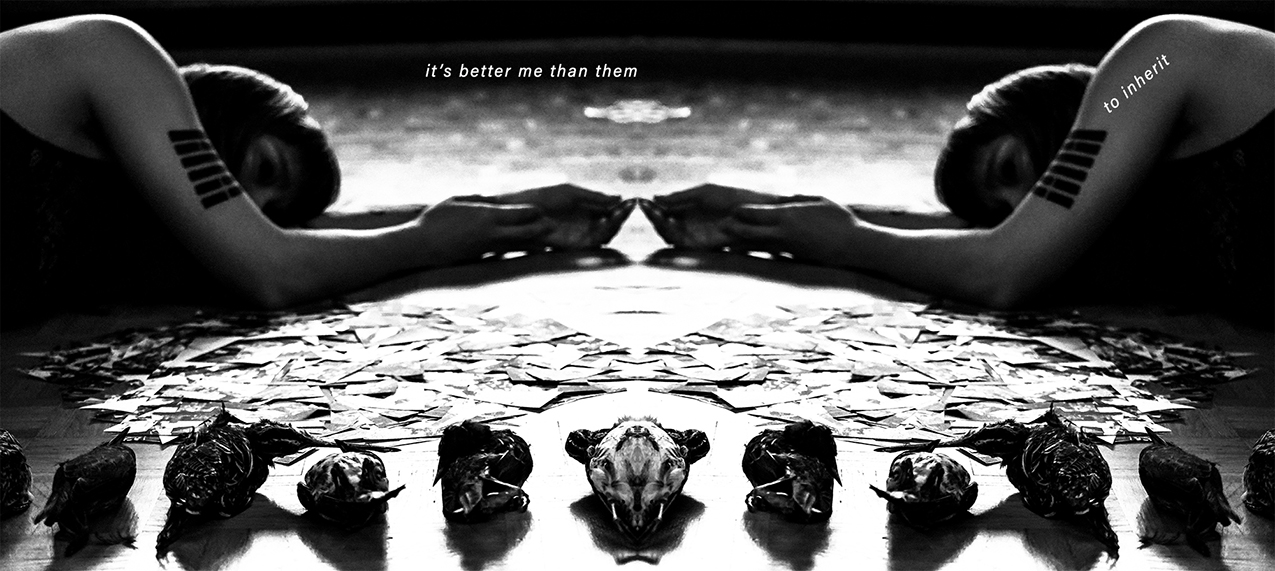

Dao Strom: I had begun to contemplate how memory is (metaphorically) an echo of an event that no longer exists concretely in the world, just as delay and echo are literally reverberations—repeats—of a sound source that has already been uttered, that is finished. For me, this is such an apt vehicle for exploring my own relationship to memory and to the past, both personal and collective; how all its lingerings are a result of both distortion and impact.

The history I come out of is very dark and horrible, in many ways, there is no denying or rewriting that and nothing I can do to escape or truly remove myself from it. So, the “grief” I sing into and out of is, for me, really a practice of diving in and extracting something out of the well. But, at the same time, I never think these utterances are a pure representation of event or emotion—in playing with sound I’m aware of how effects like delay and feedback can be very seductive, very mesmerizing. We can turn the aftermath of a sound, so to speak, into something far larger (and longer-lasting) than its source, we can change it, layering and enmeshing it with other aftermaths of sound, and from this construct a whole new experience, a new field of memory and sensation. I am interested in this as a process and what it may unfold inside us.

CS: And, the images of you with wings in so many pieces? There seems no more apt symbol than flight lately—politically, from a biodiversity perspective, and climate change. In your poem, “Hunger” you say, “History has such heavy/ feathers.” Do you see flight as something more than escape?

DS: The wings were inspired by a Vietnamese folktale about the “mother” of the Vietnamese people. She was a fairy-goddess, sometimes depicted as a bird-entity, who came down to earth and after tasting a handful of dust became grounded on Earth, unable to fly and return to her home in the higher realms, for which she was very sad; the legend goes that her tears formed the rivers that flowed to the sea.

In 1975, and in the years following, flight/escape (or not being able to) was also a prevalent motif in the Vietnamese historical-political narrative—many thousands of people fled, many also died trying to escape. And the cost of that flight—even if you succeeded—was heavy, emotionally, spiritually, and otherwise. When I inhabited the winged figure for those images, I thought of the character as a daughter-descendant of the mythical mother, a caught-wandering figure, an entity trying to revisit but who doesn’t belong entirely in any world, the earthly one or the one of flight. I suppose this may suggest that flight is also sort of an impossible dream: we can’t escape where we are, we can’t escape our earthly bonds while we are here, even as much as we may feel we don’t belong in the world as it is.

CS: So, how can we cultivate hope in a time of such loss?

DS: I believe humans have as much capacity for love as they do destruction—and that this balance is intrinsic; it will always play out, even if we may not be able to see it fully in a single lifetime. I also believe in the alchemy of the soul, that each individual is working on this and that the little amounts (of refinement, revelation, etc.) that we achieve contribute to the collective progress of humankind as a whole—so, I guess I believe in the value of the individual’s experience of feeling and seeing and attempting, however that may take shape, and this gives me what you might call hope.

I also believe in the larger view: that nature and cosmic processes will eventually subsume whatever humans do, all our beauties and horrors alike—and this smallness of our time is something I try to hold in perspective. Our woes may look calamitous but there is a larger cycle also at work and we are just a tiny piece of it, and we can only do the best we each can do.

CS: I often dream that I can speak fluent Levantine Arabic and talk with my grandmother in her first tongue.

You said, recently, in an interview with Cascadia Magazine: “Knowing language is supposed to give you access to meaning and understanding; but then does not knowing language (my lost Vietnamese, for instance) mean I cannot ever really know what it means to be Vietnamese?” How does this loss figure into your work? Or, do you see it as the struggle or bridge that fuels your art?

DS: Maybe because I am a person who lost their first language (and quickly became adept at my adopted language, English), I also discovered language is a tricky vessel, something that can be maneuvered, something I had to rely on at the same time questioning its gears, its intentions, its origins. Because many of us don’t lose our languages or certain customs of our cultures by choice (much larger conditions and systems come into play—colonialism, empire, war, displacement), I think it’s also important to question things like language and cultural customs as markers of belonging—because what does that say about how we judge or privilege one experience (or location) over another, if we deem those who retain the language (or the homeland) to be somehow “more”—authentic, entitled, etc.—than another whose circumstance was different and beyond their control? In a deep way I question everything, all the boundaries and definitions we as humans have drawn across our maps to separate us from one another; and I want to push this questioning also into how we read—which connects, fundamentally, to how we perceive. My loss/lack of language has pushed me to redefine – also – my concepts of how meaning and content and story can be conveyed; for instance, there are other forms of language, too—the body, music, image, translation, absence, silences, and so on.

CS: That is so perceptive and beautiful. Do you have any specific artistic practices that you employ to heal ancestral trauma? Do you even feel it is possible to do this through art?

DS: This is a big question that I won’t claim to have a complete answer to. I recognize there is trauma and there is need for healing. But the wounds are so immense—if you really look into them. I think art is helpful to those who have the inclination and – perhaps also – the privilege to experience it, and art uplifts and does some hard-to-measure work on the level of energy and collective consciousness. But I want to be careful not to aggrandize it. I think the important part is to say that healing is a long, slow process; or it can be. For some it may be an ongoing, multi-generational process. I will also say that I think there is a level at which trauma and healing need to be addressed collectively (especially for Vietnamese people for whom the sense of collective identity can be very strong), as well as individually.

In the last ten years one of the most connective things I’ve done has been collaboration, with other Vietnamese women writers, through a collective writing project I formed with several others, called She Who Has No Master(s). The process of sharing, both our art and personal stories, has been healing, trying, generative, bonding, fruitful, and much more. This is still evolving. The healing process is like an unfolding—it requires going deeper and deeper, and continuing to engage. Sometimes, admittedly, I get tired and wish I could divorce myself from the need of it, the conditions, but I can’t of course, so I have to go back to the perspective of: we do what we can, little by little, within ourselves and for others.

On an individual level, I consider art to be a means by which I cultivate better awareness of my own senses and self—how to see, hear, listen, voice, more acutely, to be a stronger reader of subtler currents, to become a more sensitive and receptive human being, hopefully. I don’t, in my own mind, hold healing as a goal, exactly, but rather I think of how can I make my body/being a better vessel to hold all that it needs to, to be effective and present in this world, even when what you must hold or face can be heart-breaking, overwhelming, traumatic, etc.

CS: Being “effective and present” feels possible as you say, more than “healing.” Thank you for that thought. I do, however, often feel that having my daughter witness me create or perform is a type of healing. Do you feel that way when you collaborate?

DS: What’s funny to me is that I don’t really consider myself a natural collaborator or a joiner, at all. I’ve always been more of an outsider and loner—my sun sign is in Aries, if that reveals anything, and I’ve always felt quite alone in my pursuits. So, that I’ve ended up becoming someone so invested in collaboration has surprised especially me. I’ve come to believe there is a crucial life lesson or process in this for me, in the push-and-pull between the individual and the collective in my life. I am still in the midst of following where this leads, what it is asking of me. When I collaborate, it is really a process of allowing and making space for something else to enter—things I cannot foresee or imagine on my own—and there is often an experience of magic and play and surrender in this.

CS: What keeps you up at night?

DS: So much—I often cannot sleep. I enjoy being awake and working on things. I love falling asleep when I feel sleepy but often I find myself wishing I didn’t have to sleep—this is the overactive mind wishing it could overrule the limits of the body.

CS: Yes! I love that your answer is one of joyous production. You once asked the brilliant poet Hoa Nguyen in your interview in diaCRITICS, what keeps you going? How would you answer that?

DS: I believe in working from a place of love with each move I make—by which I mean I have to care deeply about the work I do, continually—and I try to focus on the relationship between myself and the creative—forces, entities, energies—that are communicating with or through me, before concerning myself even with thoughts of who (other people) I may be writing toward or making art in hopes of reaching. Art for me is a relationship with something otherworldly, something both within and beyond myself, it is mysterious and wondrous, a process that serves the spirit and the soul regardless of whatever you may achieve with it in the outer world, and I pursue this path for those reasons foremost, before all else.

But I am also pragmatic and to that vein I will say this: you have to find some way to live that allows you to make your art, sustainably, and there is power in becoming your own production line—by this I mean that we, as artists, can empower ourselves by cultivating our own skills or by cultivating amid ourselves the relationships and resources needed to produce (make public) the art we wish to make on our own terms.

Video poem, “Flower Diatribe #1” by Dao Strom, in Poetry Northwest

Song/video, “Origin Tale” by Dao Strom explores some of the Vietnamese mother/father origin folktale that Dao mentions in this interview.