they laughed at me. When they saw the fur-lined winter coat,

they split a gut for a week. When they heard my Yankee accent,

they accused me of being a foreigner, and I was. I did not know

a black-eyed pea from succotash, and did not know cotton

could prick your finger. I did not know snipe hunting

was an initiation, and the men ducked when I swung around

with a loaded shotgun, my finger on the trigger. I learned

to never stand on a flat bottom boat. I had a bellyful of their insults:

What was the matter with you? Don’t you put chew inside your cheek?

Didn’t you know the south had won the dispute between the states?

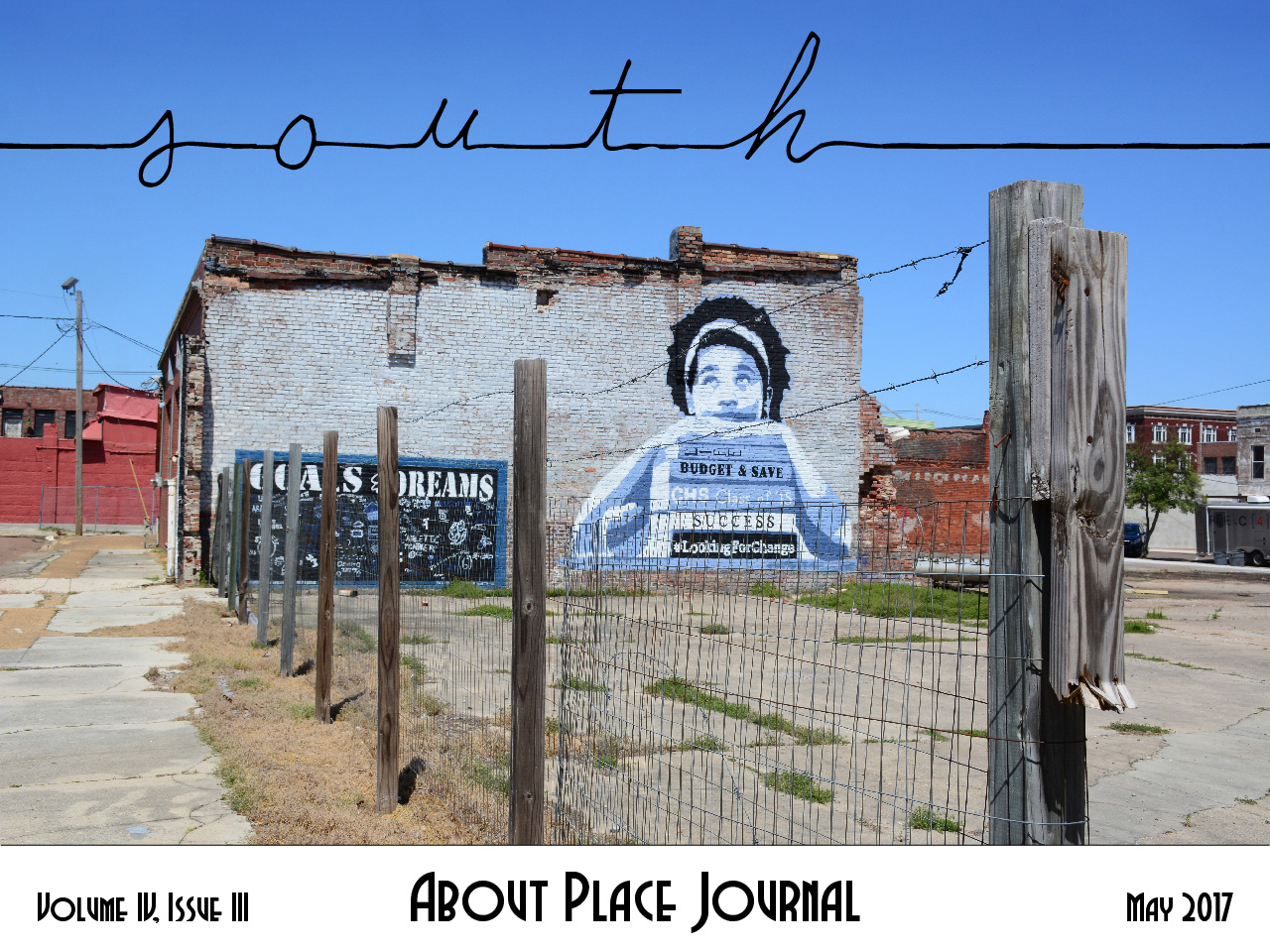

I stayed ten years; ten years too long, driving by shanties

on cinderblocks, seeing sharecroppers tiling the land

with hand plows, breaking red Georgia clay into desperation.

When I fled crossing the frost line towards New York,

I realized a part of me still craved catfish, still drawled

the slow easy way like a man putting together words

in high heat, and still had clay stuck on my shoes.

I left behind magnolias, cypress trees

with their webs of moss, the loons breaking through

clouds, deer crossing on the unpaved roads,

and if I touched corn silk, pollen would stick

to my fingers, yellow as memory, dusting everywhere.