The Rio Grande silvery minnow is not a particularly impressive fish. At three inches long and mere centimeters wide, it does not demand to be seen or claim a place on any Most Loveable Endangered Species list. If the river was clear, a school of them might look like a collection of coins glinting beneath the surface, like diamonds, or misplaced disco ball tiles. But, for the most part, they remain unknown, enshrouded by a shifting sheet of russet silt. These minnows occupy the stretches of the Rio Grande lined with cottonwood trees, known as the Bosque. Both the trees and the fish rely on floods to reproduce naturally–floods that no longer come thanks to drought, dams, and irrigation. It might sound strange to cry drought in a desert (are they not, after all, dry by definition), but in New Mexico, with an average annual rainfall of thirteen inches, the margins of survival are slim to none.

![]()

The ever-dwindling Bosque tracks a jagged green highway across the land, framed by the Sandia Mountains in the East, so named for their watermelon-colored blush at the start and end of each day, and the volcanoes in the West that sprout from the sandy earth like unmanageable black boils. The city I am from, Albuquerque, pushes up against, and oozes into the forest. It seems to be desperately, hopelessly, attempting to stay safe, hidden, and cool under the cottonwood canopy. Like our less civilized brethren, the animals, we are drawn to the little water we have. It pulses through the city and occupies our minds.

My grandmother lives on the other side of the river. When I was smaller than I am now, I wouldn’t know what to say to her looming frame. I could barely stand under her inquisitive gaze and large powerful hands. The women in my family are big, strong, and most of all, loud. They seem like mountains: unshakeable, immoveable, and inextricably linked to the land. All I, the small pale curiosity, could ever think to say in my grandmother’s house was,

“Have you seen the river today?”

We could all talk about that, my grandmother, me, my sister, aunts, and cousins. The river connected us, just as it used to connect the San Juan Mountains to the Gulf of Mexico.

![]()

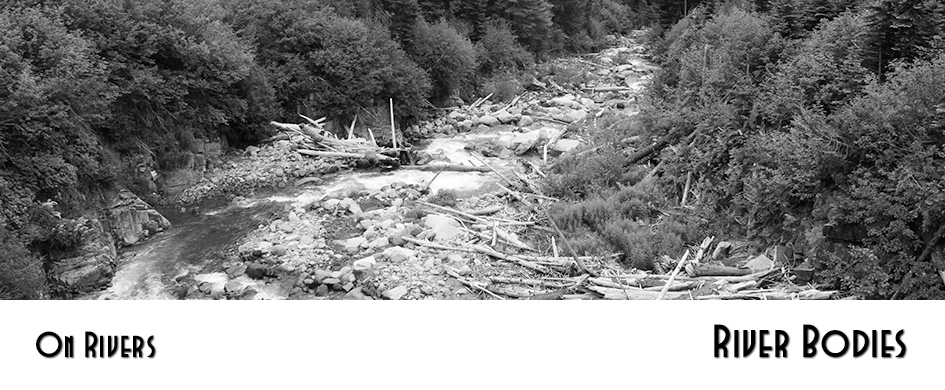

My earliest memories are of the two rivers I grew up on, the Rio Chama and the Rio Grande. The Rio Chama is a tributary of the Big River, and it is on those sun-baked banks and in that murky water that I fell in love with life outside. I suppose you could say that rafting is in my blood. My parents met kayaking and spent their twenties raft-guiding every summer. They had me on the water before my second birthday. Rafting on muddy desert rivers is an art in seeing the invisible. It is learning how to distinguish the ripple of an insect or fish from that of a barely submerged rock. Chocolate milk is what we call the water of the Chama, but it is closer to the color of cinnamon. Closer to the red of the clay than brown, or at least that is how I remember it: so vibrant that too long a soak might disguise me, make me invisible, camouflaged red against the red water. I learned how to row a raft on the Chama with my mother facing me, her knees outside of mine and hands outside of mine, half supporting the weight of the oars because I could not lift them by myself. The older I got, the less weight she would take and the fewer glances she would cast over her shoulder to assess the water ahead. I can’t remember when she stopped looking, but at some point she must have.

The Rio Grande was closer to home, but less exciting, less wet. Most summers I could wade across its girthy middle without much difficulty. Every year it gets easier; the water is lower and darker, sometimes barely more aqueous than mud. The silvery minnows have lost their once abundant habitat to this shoaling of the river; they occupy only five percent of the area they once permeated. This is a distress call for more than just one species. The silvery minnow has been described as the canary of the Rio Grande, signaling its health or malaise. If we were all miners who encountered only five out of one hundred songbirds alive, I have no doubt that all of the proper authorities would be called. Rescue teams and the media would be summoned, prayers, letters, and gift baskets would be sent, and we would do everything in our power to survive. The silvery minnows were given too little attention too late; they did not expire with the deafening silence after incessant song but slipped still and shining to a sandy unmarked grave. They, and the river, persist, but just barely.

![]()

A plan for the construction of a diversion dam designed to funnel water from the Chama back into the Rio Grande is currently underway. I wonder what that will mean for both the giving and receiving rivers. I once helped run a field study to test the amphibian populations on the Chama for the devastating Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis fungus. It grows surreptitiously, quietly coating the entire surface of its victim’s skin, slowly suffocating it. We would raft down the river, stopping at any spot that seemed like a good habitat: marshy, long grasses, rocky shaded beaches, puddles. What followed, in retrospect, was a nearly useless attempt to catch as many frogs and toads as possible and swab them for the fungus. We were using butterfly nets, for goodness sake. We would also note population size based on visual and aural surveys. I can’t help but laugh at the absurdity of it. Our measly twenty amphibians carefully swabbed and recorded, their data held up at wildlife management conferences as proof of the river’s lack of the deadly fungus. And then at night, their hundreds or thousands of cousins would mock our scientific escapades with peals of croaky laughter. Some like song, some like the gravely cough of a chain smoker, all sounding together to announce our human ineptitude while the stars winked and spun and grimaced above us and the river ran on, ever changing, ever the same. We had no chance of grasping even the slightest picture of the river’s amphibian population, no chance of understanding that place or its water. I hope its secrets survive its diversion. I hope there is just enough water to go around.

![]()

When it does rain in New Mexico you can smell it coming. The rain likes to start in the west, away from the mountains, and it sweeps across the valley floor. Sweeps is the wrong word. It roars. A silent roar, heard by our skin as it reverberates through the air, and if it rains enough, the floods come. The subtle reverberation, barely felt by the most perceptive and water hungry desert folk, becomes a rumble in our feet and ears and rib cages. The water usually stays in the massive arroyos that cut lines across the city all pointed inward, towards the waist of the city, our equator, and gravitational pull, the Rio Grande. Sometimes, however, it doesn’t, and it floods our streets and lives, but even the biggest floods don’t quench the thirst of our drying river. They don’t fill the parched aquifer and end the drought. Even the most generous downpours fade away by evening.

![]()

Family is an unbreakable unit, and the gravity of the desert holds us in place. The sand, and the heat, and the altitude are not just familiar, they are in my bones and blood and lungs. The Sandia Mountains, part of New Mexico’s portion of the Rocky Mountain range, peaks above ten thousand feet. Tourists riding the tram to the top often find their perspective shifted to a blurry upside down one, rendered unconscious by the thin dry air. Albuquerque and its surroundings aren’t exactly habitable, more survivable than anything else. Just survivable, but inescapable. Our state motto is The Land of Enchantment, but disillusioned youths call it The Land of Entrapment.

When I moved north, to Washington, I joined my sister in forbidden territory, the other, the not New Mexico. I had to say goodbye to the land and my grandmother, and I had to learn how to read water all over again. The rivers up here are clear. Rafting should have been easier, but I was so used to the river keeping secrets that I often didn’t trust what I was seeing. I was suspicious of clearly visible obstacles and hit more of them than I would like to admit. Now I am afraid I have lost my ability to pick my way down chocolate milk rivers.

There is an undeniable feeling of excess when it comes to water in Washington. When I first saw the Columbia River, I thought it was the ocean despite the geographic impossibility. There is so much rain that annual rainfall is calculated by county, not for the entire state. The rain here reminds me of the rain I saw during my semester at a small school tucked away in the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina. They told me about hookworms and to not walk in the mud barefoot to keep the wriggly little fellows from piercing the soles of my feet and making a home in my body. As a young, chronically barefoot, anxious people-pleaser in need of small rebellions, I would tempt fate and nature. Waiting for the rain like the forest. Waiting to dig my toes into fresh mud to send my roots down and anchor me in the soggy earth. Immovable and quenched. I guess hookworms don’t like an easy target.

![]()

I wonder what the silvery minnow death toll has been since I left home, what color the river is, and if any new cottonwoods have beaten the dusty odds to take seed. I wonder if my grandmother will ever forgive me for leaving.

![]()

As I write this, the Rio Grande passing through Albuquerque is running at just under 500 cubic feet per second. In 1915 the peak flow for the same section of the Rio Grande carried 4,500 cfs. 2001, the first year the Rio Grande did not reach the Gulf of Mexico, saw just 2,400 cfs on the river’s most ambitious day. Meanwhile, practically in my backyard, the Columbia River thunders on at a tantalizing 150,000 cfs. I wish I could pack some of it up and carry it home. The water we need would not be missed and it would make my grandmother happy.

The Rio Grande is not a creek that only people who have spent a bit too much time in the desert sun would defend. It is the fifth longest river in the United States and twentieth in the world: an aquatic giant brought to its knees by the mismanagement of irrigation and human consumption. The Chama diversion will help, water use restrictions will help, but it’s hard to say if those will be enough.

Two thousand miles north, I can still feel the tug of the desert and its rivers pulling at my bones. I can hear its croaking cry joining the frogs and toads on the Chama in a chorus of desperation. I hope that scientists, like those who endorsed my comical amphibian pursuits, will be heard in the unending arguments of who the water belongs to. I put trust in them because despite the inherent human error in their methods, they are the only ones stepping into rooms full of “Me!” and “Us!” to raise the whisper of “them, it.” I hope that one day I will return home to sit with my grandmother and watch the river run on, ever changing, ever the same.