It shall meander.

It shall be muddy sometimes, its depths invisible.

It may start as a trickle, a moist flush on mossy ground. Or before that even, a seepage, where underneath you might hear a roar, a deep belly ache churning against grit and rock.

There will be a whole valley of loops and lazy meanderings.

And you know, there are crocodiles beneath the surface here. Like the one in your recurring dream: always the same one, that pivots, lazy and slow, just there in the gully where the children splash. You will try to warn the others of that crocodile but they won’t see it, won’t believe you. Always you will wonder if your warnings are too weak, or the surface too muddy, impenetrable.

This river that still loops through your dreams: the dry season pulling back its water to give biscuit-dry banks that host carmine bee-eaters in darting choreography. Pulling back to make an oxbow smile.

If I am to write about this river, it will have to meander. Mother and I sat on the bank counting hippos and she taught me the word oxbow. I think I tied the word (in a bow) to the word oxpeckers, who sat on hippos backs and it came with the word symbiosis.

See, the one side of the loop is a beach, and the other a cliff.

If I am to write about this river I must write of floods: how the slow licking of the dry season tongue turns to lashing and its mouth so greedy eating chunks, munching the banks, and a whole tree falls in, a favourite spot maybe, shaded, for watching elephants cross in sunset evenings. How next year we’ll see the roots surprised and sticking out the bank like the tree was caught half dressed. You can’t grieve those trees, it’s the river’s way, and she gives back silt on the other side, powder-soft and criss-crossed with tiny tracks.

And on the cliff side, where it chews and licks and plops, one season it’ll break through, the two sides of the loop edging closer until the loop is a neck and the river cuts a new course, leaving its oxbow to become a lagoon, kapinga grassland for grazing impala, and maybe weavers nests bouncing over the now-still water.

“Mark my words,” says Mother. “Next season it will break through. Mark my words.”

And that season the waters broke – she woke to a glassy surface as far as the treeline, a teasing tongue on her doorstep and the roads hidden, baboons stranded in trees, barking.

Yes, if I write about this river, I will have to meander.

But this river feeds another. A darker, deeper, fuller river – the Zambezi. If I am to write about this river, I shall need torrents. There are places where its banks do not hold and it spills for miles, where people learned to farm the floodlands, building mounds and canoes and whole ceremonies to dance with its waters. How does it drag itself back together, marshall its energies to become the swirling depths that will surge, pound rock, whip up rapids, leap off a thunderous cliff?

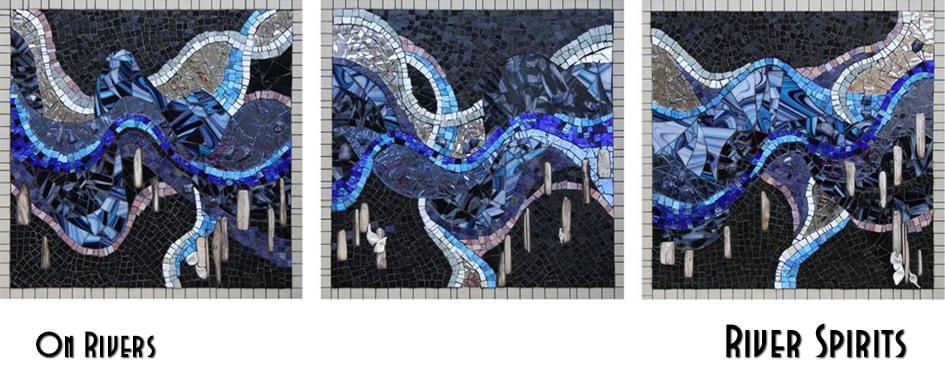

See, I thought that if I were to write about rivers I may avoid drama and violence, but I forgot about the nyaminyami: wild spirit of the Zambezi that punishes and taunts, lures you into sunny eddies and then drags you down, down and away to the parts that are too deep to speak of. I forgot about the smoke that thunders, the building climax, the roar, the part that the tourists gather to see and photograph – the rainbows, the churning cauldron.

“Come back from the edge,” said Mother, when the rainbow whispered to me, pulled me closer to the froth of the falls, and its algae-slippery curves.

I did. I stepped back from the edge and wandered inland, away from the river and into the mountains. I followed dry tracks and fell asleep on ledges, waking from dreams of the river choking, carrying plastic and detergent boxes, swirling in colours it wasn’t meant to be wearing. Woke from dreams of crocodiles, and warnings unheeded.

If I am to write about this river I must remember that sometimes there is only a trickle. Sometimes only a damp flush on the soil, and if I put my ear to the ground, I will hear the ocean, pounding.