a literary journal published by the Black Earth Institute dedicated to re-forging the links between art and spirit, earth and society

The Secret Journal of Kate Morag: A Celtic Romance

EXCERPT

I

Scotland, 1916

“Slipping in and out of one’s skin isn’t as easy as all the myths make out . . . “

March 21, 1873, low tide

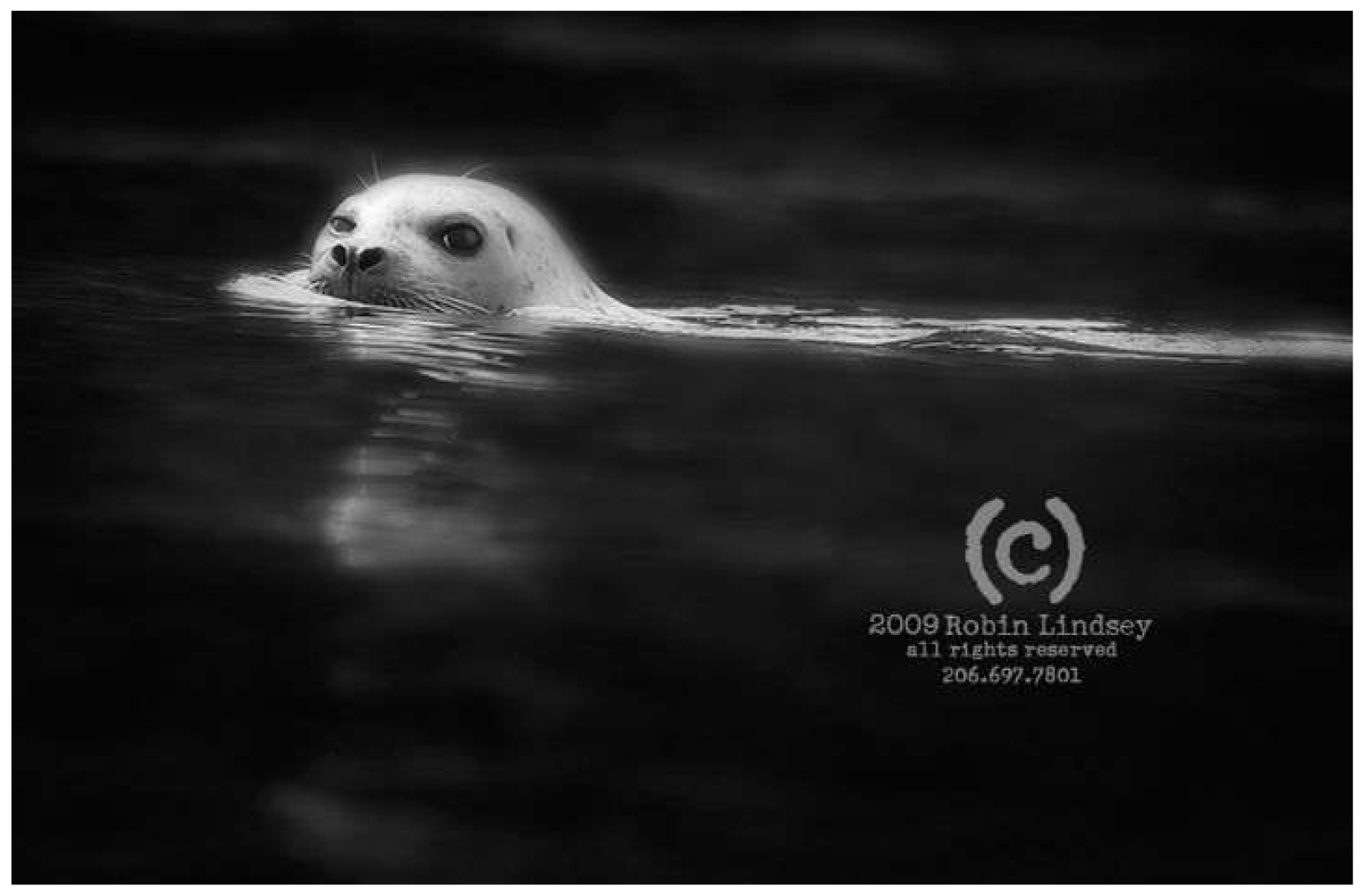

T’was warm, but stormy, and summer, the night he first washed up on my shore. This was a young seal, I thought, when I saw him lying so still on the sand. Maybe this was his first storm? I thought he was dead, the way his square head was turned halfway round, as if his face had been slapped back and forth by the waves until he passed out from the beating.

My father beats my brother, just like the new schoolteacher beats us for speaking Gaelic. Pa doesn’t mean it, but it’s the drink, you see. My brother says he will run off with the next sailing ship that comes to this island. But he doesn’t want to leave me here. When our Mum died she made him promise to look out for me. We all know how Dad can be. And it doesn’t help when there’s not enough fish or the seals swim right through his nets. The nets are too old for seal play.

My Dad, he hates the seals. But I’ve always loved the way their eyes follow you on shore. The way they don’t blink ever, but keep looking at you for so long, it’s like you are real. Or beautiful. My Mum said I was beautiful. My father says I’m trouble. Just like she was. “Too good looking for her own good,” that’s what he said. “Kept drawing me back, drawing me to her.” And then, there was her dying in childbirth. His fault, my Pa says, and that’s when he drinks the most.

Sometimes I sit with them, the seals. “Silkie folk,” that’s what the islanders call them. I’ve never paid much attention to those old stories, not even when Gram tells me she can trace her family back to these “dark ones.”

“That Eleanor Morag, she’s a dark one, she is,” the islanders will whisper so my Gram will not hear as we shop together in town. “You can see plain — she’s not one of us.”

But Gram’s hearing is still better than anybody’s. And it was Gram who taught me that even though seal’s ears are hidden — just little pinpricks in their skin — they can hear as good as humans. They can see as good on land, too.

So when I came upon the juvenile seal stretched out so helpless on the rocks like a drowned thing, I just sat nearby him. Every creature needs someone to sit vigil when they are struggling between the worlds. I would just be still with him while he died. The seal was breathing, but only a little and too fast. His lean flanks were wrinkled, as if he hadn’t gotten enough fish to eat. Or, like when his skin was still folded at birth from being inside the womb.

I must have been singing a little, like I do to babes or when I can’t sleep myself. It seemed to settle the seal and his breathing steadied. Calmer, not such a big rise and fall, a panting for air. It was then I noticed his fur, how dense and speckled. Mysterious, the way his body called to me, my hands somehow wanting to touch his deep, silver skin.

And when he spoke, it didn’t startle me a bit — so lost was I in the contemplation of his body. The drape of aerodynamic shoulders, his lean flanks, the strong hind flippers that now stretched as if his whole body was yawning. Not dying. Waking up!

“Ah, it be Kate Morag,” he said softly, his voice a little hoarse from being at sea for so long, sleeping underwater in kelp forests. “You are always in my dreams.”

“Me?” I didn’t know whether to be more startled that he knew my name or that he dreamed. Did seals dream? Could they even dream of humans?

Gram said seals did dream, just like us. They can sleep on the water and even underwater when they close their nostrils and sink into the sea to the very bottom of the ocean before they have to come up for air and breathe. Like us.

“Will you marry me, Kate?” the seal continued in his raspy voice. “Will you never go away from me again?”

“What?”

Was I daft? Could I really be hearing such a proclamation, and from a seal? Maybe it was the summer wind, so warm and weird to have such a great storm this time of year. Mum says I sleepwalk sometimes, all the way down to the beach in the middle of the night. Maybe this seal was speaking in his sleep, and to someone else!

Any other girl might have run away from this eerie visitor. Perhaps he was an apparition, or worse, a sea devil. Father Makurly has assured us that Satan can take many forms, often preferring the wiles of nature and animals to beguile us innocents. When I ask him why Moses listened to a burning bush or Noah harkened to a dove, Father Makurly snipped, “Eve listened to a serpent, my girl . . . and you know what came of the whole world after that!

The thought of our old priest and his endless and boring catechisms made me bold. I stood up straight and carefully crawled over the rocks closer to the stranded creature. “Who be ye?” I demanded in a voice that was more commanding than I felt.

Really, I felt anything but brave. My knees were wobbling and I caught myself from losing my balance on the one last boulder that separated us — me and this creature who not only talked, but who I understood.

Silence. Only the shushing of strong winds. “Again, I ask ye, what kind of creature?”

And then his great eyes open. Dark and unblinking, fathoms deep. They might as well be mirrors. For I see myself reflected in these eyes. But I am not the Kate Morag I see in my own small hand mirror. I am an older woman with hair the color of coral, wound in luxurious braids around my head. More than that, I am rounder, with womanly hips and a strange woven necklace that falls over my generous breasts. Whatever the reason, the image of me I see reflected in the seal’s huge eyes show a woman of distinction and great beauty, someone I might only aspire to grow into.

“Marry me, my Kate,” the seal said again and in his voice was so much sorrow and hope I couldn’t bear the music of it. “For the sake of our child.”

Suddenly I am running, tripping, falling over beach rocks whose flint sharpness cuts my knees, my thighs. I may also be screaming. I cannot know because the wind carries my voice away from me. Does he hear me, this creature who speaks like a man but whose body is still that of a juvenile seal? Is he dying down there on the rocks alone — now that I have forsaken him?

It is the thought of him facing death in such a storm, such solitude that stops me. For a long time, I stand on the wet sand, the surf coming nearer, gravitational pull of tide sucking my feet deeper. Soon it will be high tide and the rocks where the seal lay covered with seawater. If he is too injured to swim away, if he is still dreaming, the seal will drown.

He may be strange, he may be a demon, as Father Makurly is always predicting will get me — but he must not drown. Too many of us islanders and sea creatures die of drowning. It is the one thing we must try to prevent, if it is in our power.

So I clamber over beach rocks, slipping on kelp, to come back to the seal — and do what? He is too heavy to lift; he is too strange to touch. But this doesn’t stop me. I run until I am breathless and my heart is clanging in my chest.

Yes, he is still lying there and the tide is almost upon him. Down now on all all fours, I climb up the boulders. Barnacles cut into my hands and knees as I crawl up. I can almost touch his silver skin.

My hands cannot help themselves from reaching out and resting, palms flat, on that shining, soft skin. It is warm, quicksilver, a fur deeper and silkier than sheep or dog, even my favorite Eriskay Island pony. It is as if I’ve never felt fur before — or the first time I felt fur as a child when I grabbed hold of my pony’s shaggy foreleg to pull myself up and toddle. And my Mum laughed out loud, saying, “Our Kate, she knows how to let other animals help her along in this life.”

“Please, you must swim away,” I tell the seal, my hand still on his silver flanks.

Only then do I notice that he is not breathing anymore. He has died alone, and without me — someone he thought he knew, at least in his dreams. The weight of his suffering overwhelms me and I sit down on the rocks, weeping.

It is not like me at all to weep. Often, I have much to cry about. But those times I just squint my face up and dig my nails into my forearms. We’ve had enough crying around here, I tell myself then.

But now I not only weep, I wail. As if the summer storm is now moving inside me and these tears are just warm rain. I shout out the injustice of such a short life — that this radiant sealskin, still so warm to the touch, will soon cool — and I must bury another short life on this beach.

I bury my face in the silver skin. To my shock, I can easily pick up this creature and cradle him in my arms. He smells of the sea, of brine and north wind. He is light in my embrace. Too light.

And then I realize. He is gone. I am holding sealskin from an animal I did not kill or flense. I am the one who is alone here on the beach. And how will I ever explain this mystery — that a seal slipped out of his skin, as if to leave it to me as a gift? For though no Eriskay Islander will kill a seal, we know their luxurious pelts bring a large price on the mainland for women’s furs or men’s great coats.

But I would never sell; never part with such a prize. I must hide this sealskin and keep it with me forever. I know this without understanding how I know it. Perhaps Gram’s stories have gotten into my head — or the dark ones are still in my blood. I am just tenderly wrapping the dense folds of fur in my Macintosh and trying to think of a hiding place when I hear a voice I recognize right behind me.

“Ah, Kate Morag,” the rasp is now lighter but still distinctive. He coughs slightly and clears his throat. There is humor and courtesy in that voice. “You’ll be keeping my skin safe, I see. I will need it from time to time — to fish for us and our family.”

I close my eyes, knowing that when I turn around I will see him. And we will know each other from a time that may not be now, but may be in our future.

“Tell me your name,” I ask and at last turn to look up at a dark-haired boy with great, black eyes, a sun-blasted face, and a smile that slightly mocks me. But there is such tenderness in his eyes, such recognition, even pure happiness, that I cannot look away. Or down.

He cocks his head and arches one eyebrow, “Ach, so you haven’t met me yet?” he grins and nods as if amused by some fate I cannot fathom. “Time is always so hard to pinpoint, isn’t it?”

“Yes . . . ah, yes,” I say, stumbling over my words.

“We are young,” he says simply and sits down beside me on the boulder. I notice as he sits, he winces a little as if his long legs are a little uncertain of how to fold. “We are just at the beginning of it all,” he tells me and then he takes my hand as if I belong to him, just like the silvery skin I still hold in my arms.~

Brenda Peterson is a nature writer and novelist, author of 17 books including Duck and Cover, a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year,” and the recent memoir, I Want to Be Left Behind: Finding Rapture Here on Earth, which was selected among “Top Ten Best Non-Fiction Books of the Year” by The Christian Science Monitor. Her new children’s book, Seal Pup Rescue, is just out from Farrar, Straus, Giroux and her new YA fantasy novel is The Drowning World. This story is an excerpt from The Secret Journal of Kate Morag: A Celtic Romance. Patricia Monaghan published Brenda’s “Selkies: An Interspecies Love Story” for her Goddesses in World Cultures series. Brenda is a BEI fellow. www.BrendaPetersonBooks.com

©2026 Black Earth Institute. All rights reserved. | ISSN# 2327-784X | Site Admin