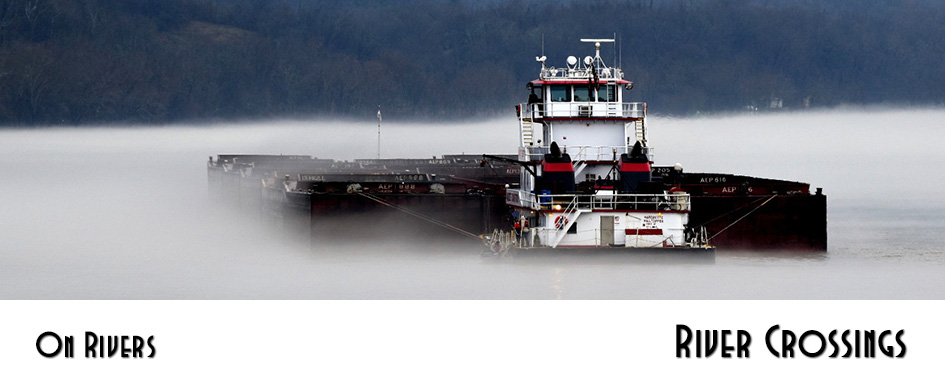

right arm bent against the ferry’s stout frame. A mile out,

the opposite shore smears in dank expanse, sycamores

dense in the owl-dark of June. In the foreground,

heat radiates from fenders of Chevys parked

in rows of three on the deck. There is a sun so warm

you mistake it for sleep. How easily the photographer’s

gaze opens a hole in me. My great grandfather, collector

of ease, architect of routine, captured

her best in the language of her skepticism. I believe

her thoughts tilt toward the unknowable. Could

it be me, a chance reckoning with the future?

Here she is wholly present, spirited

as a child, pink headscarf tied in the shape

of a bell, so bright it rings. Her frown

deepens to a singular point and I know

what she would say, Is this not enough? She’d be right,

I’ve spent enough time peering through albums

until I see myself staring back as if I didn’t know

my own regrets—memorabilia I don’t recognize,

family that doesn’t know me. Give me the refusal

to adapt as a girl must. I’m where the self

finds another name, two generations away—

but can the heart be so sick with yearning

it cleaves blood-fat clots from its burled arteries?

Suppose I tell her where I am, how leaving

the country meant paying off my debt. I’m still

out here giving what I have to these jarred-in mornings

of stream frogs and dust. Suspended, not unlike

her, above an eventuality clouded and stirred

by current. That I have never come back. What then?

If I tell her it’s loneliness that raised me, will it mean

I can come home through buckeye-sought

roots, through the wild rye and dropseed, spread against

the night like thinning hair? Beneath the silt-heavy

willows, warm music from the eastern shore

warps forward like an under-bite. Already,

I sense myself on the other side, furred with sweat.

The ferry pulls beneath the winding of insects.

Forever, the sputtering of engines rev in the wrong gear.