March 2023

Introduction

Poet, activist and historian Peter Carroll has published eight books of poetry. Before he came to poetry, he published widely on American history and culture. The Free and the Unfree is a well-regarded overview of U.S. history, which pays particular attention to themes of indigenous genocide and chattel slavery. Famous in America examines the lives of four “famous” Americans—astronaut John Glenn, conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, antiwar feminist Jane Fonda, and racist demagogue George Wallace—whose lives mirror the complexity and struggle within mid-20th century American culture.

His memoir, Keeping Time, which has been described as “A brilliant, witty, touching and consistently thoughtful book,” traces his journey from the working class Bronx to the halls of academe, and illustrates the ways in which his origins influence his choices as a thinker and scholar.

After leaving a tenured position in the Midwest, he re-located to northern California, where he became a beacon of the literary culture in the San Francisco Bay Area—book editor for the Bay Guardian and a founder of the Bay Area Book Awards—as well as friend and confidant to many of the Bay Area’s leading literary lights.

In addition, he has been an exponent of progressive ideals for over 50 years. In the 1980s he became interested in an earlier generation of progressives, the volunteers of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, who fought against Franco’s fascists during the Spanish Civil War. He was instrumental in building the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archive, interviewing survivors, raising money, and editing the newsletter. Currently he is poetry moderator for Portside.org, a website which features news and cultural information of interest to progressives.

For the last 15 years he has also devoted himself to poetry.

His first poetry collection, Riverborne: a Mississippi Requiem, published in 2008, takes as its starting point a personal trip down the Mississippi. Along with a fellow historian, a friend named Jim (!), he is accompanied by an earlier habitué of the river, Mark Twain. Like Twain, his goal is to uncover the darkness at the heart of America. This interest reappears throughout his work. In “Progress,” for instance, from his collection, Fracking Dakota: Poems for a Wounded Land, he critiques the myth of racial peace, so common in the American South, as well as the more general American myth of continual progress. In Mississippi he finds a monument to mob violence and racial hatred:

On a dark street, a neon bus flashes

pink, marks the spot,

mobs attacking Freedom Rides.

His most recent book This Land, These People: the 50 States (the 2022 winner of the Prize Americana) again reiterates this concern, voicing his outrage at the way racism has crippled the American Dream.

Until the coming of railroads in the 1830s, rivers were the main arteries for the transportation of people and goods into and out of the interior of North America. They were the focus of exploitation and oppression. King Cotton traveled the Mississippi to New Orleans and built the palaces of the cotton factors. Huck and Jim traveled the river out of slave Missouri, hoping to find freedom, but went too far south. Slaves fled north but the Fugitive Slave Act dragged them back south in chains.

In our own day, rivers continue to be crucial to the economic life of the nation, but they also embody a history of separation and oppression. The Rio Grande divides US from THEM, keeps THEM apart from US, the distance of a river. We descendants of European colonists have taken a Wilderness and made it ours; as Conrad says in “Heart of Darkness,” “we are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster.” But we wear the shackles as well, as do the peoples we have conquered or captured, those who do our work for us.

* * * * *

Lee Rossi: Can you tell us what brought you to poetry, after many years of other kinds of writing, and why was it that you focused on the river, the Mississippi?

Peter Neil Carroll: I have always been interested in reading and writing poetry, mostly North American poetry that I could bring to students taking my classes in US history. For five years, I lived in the Twin Cities (1969–1974) where the University campus is cut in half by the Mississippi River. I crossed the big bridge over that river hundreds of times, often pausing to watch the waters running down to a bend that abruptly stopped the view. Once I had driven with a friend I call “Jim” along the river to New Orleans, saw for the first time cotton growing in southern fields.

Thirty years later, I started writing poetry more seriously. You ask why? Partly because I was tired of long 500–1,000 page manuscripts that I had produced. But mostly I wanted to tap into my emotional experiences as a reader, traveler, historian.

As a novice poet, I was haunted by some of the things that we had seen on that earlier trip down the river with Jim. I had some sketchy memories and when I called him to ask what he remembered, he had the same short list. So we agreed to go down the river again, a slightly different route beginning at the St. Croix river and approaching its confluence with the Mississippi from the east shore.

Lee: What does the Mississippi mean to you and to what extent does it embody the major themes of your work?

Peter: There are two branches to discussing the river and my work as a cultural historian, one examining societies around waterways, the other a bit more abstract that I absorbed from a philosophy professor, John J. McDermott.

The more obvious one is that I see the Mississippi river as the spine of the nation, the long channel that carries goods and services from north to south and, after the age of steam, south to north. I think that’s the way Mark Twain saw the river.

His vision emerges most clearly in the passage of Huck Finn and Jim on the raft. The whole of American culture, in my view, reflects the power of the river not just as a symbol or metaphor but also as a critical reality. Jim in Twain’s eyes is a runaway slave and Huck is his co-conspirator. They plan to follow Big Muddy to the mouth of the Ohio River, placing Jim in a free state. But in the novel, Twain makes them pass the confluence of rivers. What then? Twain put down his pen and didn’t pick it up to finish the story for seven years. And surely the aftermath becomes a gothic show based on medieval chivalry.

Lee: Twain was obviously aware that rivers, especially the Mississippi, not only separated free from slave (Illinois from Missouri) but connected them, farm states and cotton states all dependent on the river to move their goods. Which is more important, do you think, in the American imagination, separating or uniting?

Peter: Slavery and race are linked to the nation’s rivers—borders and boundaries for the free and the unfree. It’s the tale of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Eliza crossing the Ohio in the winter to escape her enslavers. More contemporary, Toni Morrison’s Beloved also depicts the importance of the confluence of rivers, Ohio being the route of escape and Kentucky the forbidden place of enslavement. Coming down in time, it’s the story of the Civil War and the underbelly of our current Red States vs. Blue States.

This came out for me on one of my road trips with Jim along the Kentucky side of the Ohio River. We took a turnoff into a small town, Vanceburg, and came upon a large monument that declares THE WAR FOR THE UNION WAS RIGHT, EVERLASTINGLY RIGHT, chiseled into the stone façade. I believe this is a unique admission about a serious political battle that had occurred in this tiny town from Civil War days. And what I also saw there was the proximity of a small boat chugging up the blue Ohio that at one time had separated slavery from free people.

It comes out in one of my poems, “Everlasting”:

Blue smoke hangs like mist

over two frizzy-haired women sitting

cross-legged, backs against

a brick wall, savoring morning cigarettes….

At the court house, a column honors Civil War dead,

deeper in the etched script, a stormy history sleeps:

The War for the Union Was Right, Everlastingly Right,

and the War Against the Union Was Wrong, Everlastingly Wrong.

Such fervor—and down the block,

the two women stand up,

flip away their cold smokes, glance

toward the Ohio River a hundred yards away,

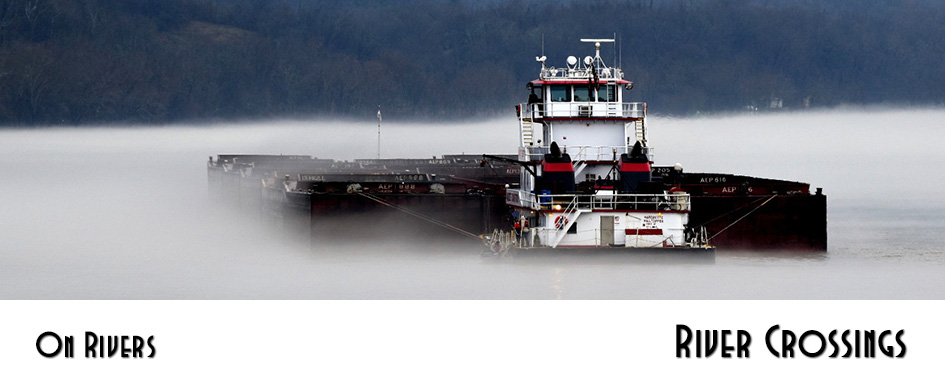

a tugboat stubbornly pushing against the stream

that separated slave from free.

Lee: Once upon a time, before our European ancestors divided their conquests into slave states and “free” states, they warred against the indigenous peoples who’d been here for thousands of years, bringing “civilization” to the “wilderness.” How does the Mississippi figure into that struggle?

Peter: One other thing about boundaries: the Mississippi served white settlers of the Midwest as a boundary between “garden” or “civilization” and the wild “wilderness.” To protect the advance of white settlement, Illinois whites expelled the Sac and Fox people across the river toward the west. And when the Native chief Black Hawk returned with warriors four years later, it sparked the Black Hawk War, in which both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis served in the militia and were rewarded with grants of land. Similarly, when white Christians destroyed the Mormon colony at Nauvoo, Illinois, the survivors dispersed across the river, eventually stopping in what is now the state of Utah.

Lee: You mentioned earlier that there were two streams in your work. What about the second, the more abstract, philosophical one?

Peter: Yes, of course. The second theme in my work as a historian/poet is a question involving all rivers: Is a river a place? Or a series of places, like a film strip of distinct places—that keeps the country in everlasting motion, a channel for ideas and emotion. I’m reminded of a joke made by civil rights advocate Dick Gregory in the 1960s, a reference to southern bigotry:

Why did jazz come up the Mississippi river from New Orleans?

Answer: the musicians couldn’t go by bus.

More seriously, the American philosopher William James proposed the idea that human thought follows a stream of consciousness, sometimes moving rapidly, sometimes pausing like a bird resting on a perch, then taking flight again. His disciple, the philosopher John Dewey, added that “the nectar is in the journey.”

Those insights illuminate our human fascination with moving waters, our desire always to seek more, the varieties of the natural world and, for example, an urge to protect endangered species, save the planet.

These points help explain the marriage of ideas with the emotions of poetry. Both prose and poetry can tell a story, evoke memories and feelings, but for me the burden of writing poetry is to touch the heart of the matter and express it in a way that will move the reader to their own emotional experience.

Lee: Let’s turn for a moment to another river, one that’s in the news a lot, the Rio Grande. In A Child Turns Back to Wave, we notice that a kind of stasis, almost death, has invaded the place: “Nothing moves . . . but the drawling river / mud-creased, deep enough to swallow a man / to his hips or scuttle a raft of refugees.” We hear the drawl of the occupiers, we see a man swallowed. The river is a boundary, a place of separation, whereas in terms of the environment, it’s what gives life to an arid landscape. How do you view the government’s efforts to stem the flow of migrants from Central and South America?

Peter: Yes, we see another North American river these days, the Rio Grande, as a pathway for desperate people seeking entry into the United States, but now surrounded by barriers aimed to keep them out. Does the river care? On which side is the river? It has no feelings, as I wrote in A Child Turns Back to Wave, a bare description of an inert waterway.

“The border’s porous as heat but no coyote dares/

sneak through the unguarded crossing before dark.

People cross that border at their peril—and not because it’s a fierce river. The geographic situation is similar to the story of the Ohio.

Which reminds me of my second journey down the Mississippi with Jim in 2005. We drove directly from the gambling fields of Vicksburg (once the largest inland port of the slave trade) towards New Orleans only to run into the rough weather of Hurricane Katrina. We had to quit, turn around, escape by the skin of our teeth.

Lee: You have a poem in your latest book This Land, These People that I admire very much. The title is “Louisiana: Postscript to a Flood,” and it’s got an epigraph from Twain that references Noah and the Biblical flood. But, as I read it, your moral is neither moral nor religious. You say: “The river’s a planetary seam, / doesn’t reason or think, love or hate . . . the Mississippi outlasts every desire.” One might extrapolate from lines like that and call your view of nature materialist or even reductionist. How do you see it?

Peter: Having followed the Mississippi during flood seasons, there’s a temptation to see the water as a living object. The Mississippi is famous as a river that changes its channels, makes cuts over dry lands and leaves behind acres of dry runnels. Yes, you can blame the forces of gravity, but it makes the river seem like a living entity, even absent its streams of consciousness or fantasy.

Lee: In your poem “Tennessee: Home of the Blues” we see the narrator reacting to the shocking vastness of the river: “Here the river stretches from cotton fields / to cobbled streets, waters born 800 miles above / rush toward unsuspecting acres 400 miles below, / subverts the human scale.” I would imagine that as a historian you tend to take the long view, deeply discounting the works of man. Is that what you’re saying here?

Peter: Actually, I think it’s the vastness of the Mississippi that permits people to introduce their own perceptions of what is before them, it enhances vague mysteries of people interacting with the currents. Standing at the western shores of Hannibal, Missouri—Mark Twain’s hometown, now calling itself America’s Home Town—I tried to imagine what it felt like to a boy who could not see beyond the river’s bends. (I had the same problem up in Minnesota.) Looking at the swirling water clogged with bits of leaves and dead trees, you might begin to picture pirates and treasure chests, even corpses. You can understand, perhaps, why Mark Twain was passionate about leaving home, traveled the world, and returned to the river only once in his lifetime.

Lee: I think you’re talking about your poem “Missouri” [in This Land These People]. I get something a little different out of it, the contrast between the boy who longs for adventure, for change, and the older man who has a more realistic appraisal of life: “the fast current spins dead limbs into soft eddies, pulling round, round, like a treading swimmer.” Is that what contemplating a natural wonder like the river leaves us with, a sense of being subject to or trapped in the eternal cycles of nature?

Peter: In this era of climate change, Lee, I wonder if there are eternal cycles of nature. We’re certainly trapped by forces of gravity and chemical changes in living creatures, but it’s a long view for most people. I think most people have a desire to leave something of themselves behind—whether it’s children or carving initials on a tree or writing poetry. In the long run, John Keynes famously said, we’re all gone. Those who deny climate change also deny mortality.

Lee: Yet I notice that rivers also evoke a kind of euphoria in your work. I’m thinking about “New York: Crossing from Brooklyn,” which begins with a lovely epigraph from Whitman: “And you that shall cross from shore to shore years hence are more to me . . . than you might suppose.” At one point in the poem you observe the activity on the East River: “swarming with tugboats and ferries and kayaks, young muscular men racing on jet skis, blue police boats making their rounds.” It’s all very colorful and frenetic with a subtle homoerotic charge. The narrator knows that even here one could be cynical, and yet he says, “The sun is real, the air suffused with Atlantic salt, great skylines: buildings shining on both shores.” What do you want us to take from your portrait of the East River, a relatively minor stream, as compared to the mighty Mississippi.

Peter: Before there were bridges, Walt Whitman commuted by ferry from Pomonok (Long Island) to Manhattan, across the timid East River, and depicted the sights and people he saw. As a self-assured poet, he wrote that epigraph to future readers of his poetry. But rivers are not only a means of transportation. They’re also the main reason for building bridges. Brooklyn Bridge, built in the 19th century, has become an iconic structure of industrial progress, that there is a future that Whitman hinted at in addressing his posthumous audience.

My own journeys across Whitman’s commute were pedestrian, literally, surrounded by masses of people, mostly tourists, ecstatic at the wonders of technology and the joy of their own love for life. Hardly anyone paused to look down at the busy river, except to take selfies with the bridge and neighboring skyscrapers as background. I admit it was euphoric but…

Lee: I noticed something similar in “The North River,” a poem from your book Talking to Strangers. In the poem the poet meets a bearded gent [a Whitman avatar?], “a kindred spirit,” who pointing to the Narrows where the Hudson flows into the Atlantic, says, “That’s the magic spot where water touches the sky.” He’s a poet too, with an un-American approach to the riches which surround him: “He’s excited for what he can never own—the river, the boats, the sun. I come to get away from my life.” We assume that this man has a typical life with the usual joys and unhappiness, and yet, as the poet tells us, “The river hears his loneliness.” Do you go to nature for consolation? How about poetry?

Peter: Waterways are certainly places of consolation, but I’m not sure why. The guy I met was a retired working stiff aware that his family life wasn’t what he wished it to have been. When I lived in the Midwest I loved to disappear on the shores of rivers and lakes, sometimes finding escape from troubles. Now I live fairly close to the Pacific Ocean and it has the same calming effect. It’s like moving to another country, your worries left behind.

When talking about the North River, which is a tidal river, I think about the long stretch of human time that has followed its so-called “discovery” by Henry Hudson. Remember I mentioned William James. What he called “perches” or resting places in our streams of consciousness brings the rivers back to a human scale. Consider how much in five hundred years of history the people here have changed—the first people, the Lenapi, then Dutch, English, European, Puerto Rican, Asian, African, Latinx—while the habits of the river simply follow the phases of the moon.

Lee: Your references to William James and his idea about the stream of consciousness reminded me that we all swim in the giant stream of American culture. So who besides Twain and James and Dewey, those stalwarts of the Progressive Era, are the writers you read for inspiration, who propel you further along, further into the future? Any contemporary writers?

Peter: I was a late starter in poetry, dabbled in the writings of Whitman and the Beats, but as I plumbed deeper a strong influence came from Philip Levine—his accessible language, a worker’s vernacular, and a pleasant sense of humor. Life is not easy with Levine or Carroll, but there’s plenty of irony to accompany our grievances. I often engage in conversations with strangers, people I meet while traveling; they tend to be more open because they remain anonymous. Rivers, lakes, beaches and perches—these are places where you can tap into other people’s thoughts without having the responsibility of seeing them again.

Lee: So what do you want to tell us about the state of American poetry? Is it a slough, a becalmed back water, or is it part of a larger movement, something that will cleanse and purify the Big Muddy?

Peter: I don’t think we’re about to cleanse or purify Big Muddy, far from it. In the last half century American voices have enlarged tremendously, bringing in varieties of ethnic poets, gender poets, multi-lingual poets which most people who write poetry today acclaim and endorse. Nonetheless, this multiplicity doesn’t lend itself easily to a consensus. In past times, there was agreement about who the major poets were, with a few outliers. I feel now a fragmentation that is healthy; everyone can be a poet, why not? But as a Fortune 500 CEO once told me, You can be anything you want in America as long as you don’t get paid for it. Or as Fitzgerald said, the rich are not like you and me.

Lee: Lives are streams that end in the one big river. Where is your life taking you? What new projects are around the bend?

Peter: I think I’m still improving as a writer. I try to write with the fewest words possible about things that matter most to me. Among the various hats I’ve worn, there’s a strong activist impulse in my heart. One thing, I am the Poetry Moderator of an all-volunteer online journal called Portside.org. That’s the left side of a ship and where my heart is turning ever. Among the “causes” I support is a clear antipathy to fascism and quasi-fascism (a distinction without a difference). One of my literary “hobbies” focuses on the Spanish Civil War, more particularly the North Americans who volunteered in the 1930s for the Abraham Lincoln Brigade who fought unsuccessfully against the fascist coup that destroyed the Spanish Republic.

Lee: Twenty, thirty years ago critics were lamenting the fact that American poetry seemed so apolitical. Yet your poetry seems imbued with political, historical and social insight. What has changed or shifted in American society to make politics a more suitable topic for poetry?

Peter: I think it’s part of the democratization of poetics. Poetry doesn’t belong only to people who have PhDs. In my case, I began collecting oral histories of the veterans of the Lincoln Brigade which led to a prose book about those 2,800 brave men and women who put their lives on the line (one third were killed in Spain) to stop Hitler and Mussolini before World War II. After writing about them, I was invited to become an Associate member of the veterans group and did a lot of writing for their anti-fascist projects, such as sending humanitarian medical aid to Nicaragua, South Africa, and Cuba. As I poet I have written about those issues and I’m now completing a book-length collection of poems depicting some of their lives, some who died in Spain, some who lived to old age.

Like them, that’s where we are all heading. Remember that old expression: Go jump in the river!

Lee: What haven’t I asked that you want to share with the readers of About Place?

Peter: I’ve written so much “about place”—from my first book, Puritanism & the Wilderness to Riverborne and eco-poetry—I find it’s a topic that matters to everyone’s life. Native Americans measured time by seasons and cycles of nature rather than linear time, by dates, clocks and watches. So, too, they remembered events of importance—a battle, say, or a ceremonial event—not by when it happened in calendar time, but where it happened. They honored what we call history by marking sacred places. And that makes every place important potentially. Of course, that’s a generalization; there are exceptions. But I find thinking about history as a place in space, not just a moment in time, adds another dimension to keeping alive memory as a lesson from the past and a road toward the future. And I go back to asking—inverting my earlier question—Isn’t a river a place?