In times of pain, a friend told me, go to moving water.

So we go.

I stand beside my father, we are both bundled against the winter cold. We watch the black and silver river flow past, below us a few boats rocking in their moorings. We are not far—perhaps only a quarter mile—from the place where he and my uncles launched the sailboat, a 22-foot New Haven Sharpie, that they built with their own hands when they were young men and could do anything.

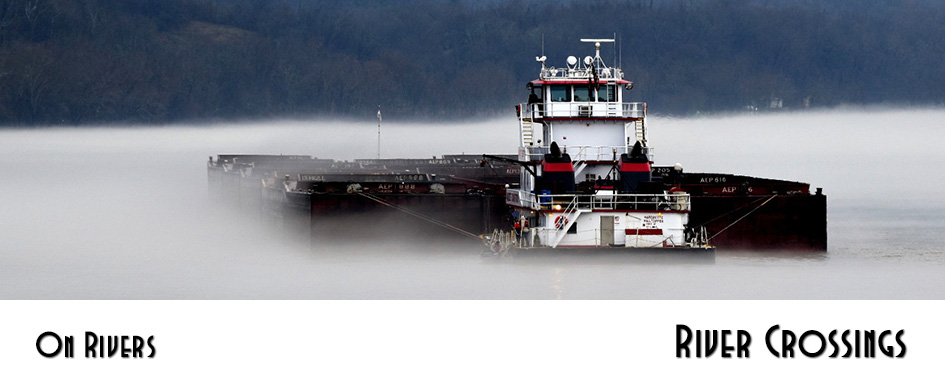

My father is in his wheelchair, staring out over the river. I’m not sure he knows where he is, on this river where he launched so many boats, taught so many young people to sail, to love the water and the wind.

I share with him a quiet time of rare peace.

It wasn’t a sailing river—too narrow, winds shifty and uncertain, no space for a long reach. No whiff of salt on the air. An urban river, lined with city. But a sailor takes to the water he’s given. He learned to play its games. He loved sailing in the dark, under all the bridges, lights glittering on the water.

It feels like a betrayal to take this old sailor away from the river. But he is cold and will soon be tired, will need warmth and a restroom and a book to read and a nap.

So as we watch the river I am silently developing my strategy for navigating the steps ahead, a mental rehearsal. Each move takes planning although we have done it all many times:

How I’ll turn the wheelchair and push it back up the ramp. Keys ready, reach to open the door. Angle the chair close to the car, flip the foot rests out of the way, set the brake. Strike the sails, coil the lines—no, that’s sailing.

Remind him to turn and sit down on the passenger seat first, then help him bring his legs into the car. Lean over him to fasten the seat belt. Fold the chair and heft it into the back. Drive the roads he no longer recognizes, find a parking place with room to unload. Wrestle the chair out of the back, park it beside the front door. Support his struggle back into the chair. Push it across the asphalt of the parking lot and through the double sliding doors and back to the room where he is cared for and doesn’t know why he is there.

Every step is complicated but the two of us will manage.

I take off the brake and turn the chair up the ramp. He looks at me and says, “I’m sorry.”

And the river moves on.