“I want to see things with my own eyes,” I replied when asked why I was driving along the US Mexico Border Wall in the summer of 2019. My intent was to photograph a 7′ inflatable helium globe along border towns in West Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California, commenting on our country’s relationship and ideological differences with this boundary line.

My association with the border comes from my family’s origins in Southern California and the six years I lived in Tucson, Arizona and Houston, Texas. Crossing into Tijuana, Tecate, Sonoyta, Nogales, Naco, Aqua Prieta, Boquillas del Carmen, and Ciudad Acuña was a regular occurrence when the opportunity arose. As a teenager, I saw a screaming Mexican woman dropped by her friends into the arms of the police as she was unable to pull herself over the wall at the US checkpoint in Tijuana. I was a passenger in Sonoyta where Mexican officials planted a bag of marijuana under the front license plate to “test the dogs” without informing us. I crossed the Rio Grande in a small rowboat to arrive in the tiny town of Boquillas del Carmen shortly after 9/11, learning the next day that activity was no longer legal. Moving freely between countries, albeit with great privilege, is what I had always known but now, the circumstances had changed radically.

In the two week span of my journey, the following transpired: the Supreme Court overturned an appellate decision and allowed the Trump administration to use $2.5 billion in Pentagon money for the wall’s construction; Donald Trump Jr. attended the WeBuildTheWall symposium in support of Sunland Park residents who took it upon themselves to erect their own wall over public and private land in New Mexico; three days after leaving El Paso, a mass shooting occurred at a Walmart, targeting Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, killing 23 and injuring 23 others; and Ronald Rael’s Teeter-Totter Wall went viral as citizens from both sides of the border played with one another on pink seesaws. Simultaneously, I inflated and deflated the helium balloon, photographed it in Santa Elena Canyon, the Sierrita Mountains, and Border Field State Park. I quickly became more interested in talking to strangers and family, taking detailed notes about their experiences living and working this close to Mexico.

In the spring of 2020 during Covid-19, I constructed these barriers in my basement as close to the descriptions as possible, using popsicle sticks, painter’s tape, Brillo pads, copper tubing, string, and brass stock. I illuminated these jury-rigged creations with an iPhone suspended from the ceiling, generating shadows which I projected over photographs and screen captures of relevant landscapes. The boundary lines and the stories I gathered were now intertwined. The sharp edges drawn on a map were suddenly blurred. The Rio Grande and Tijuana River Estuary marked the end of one country and the beginning of another, but also a melded culture and a historical and political divide.

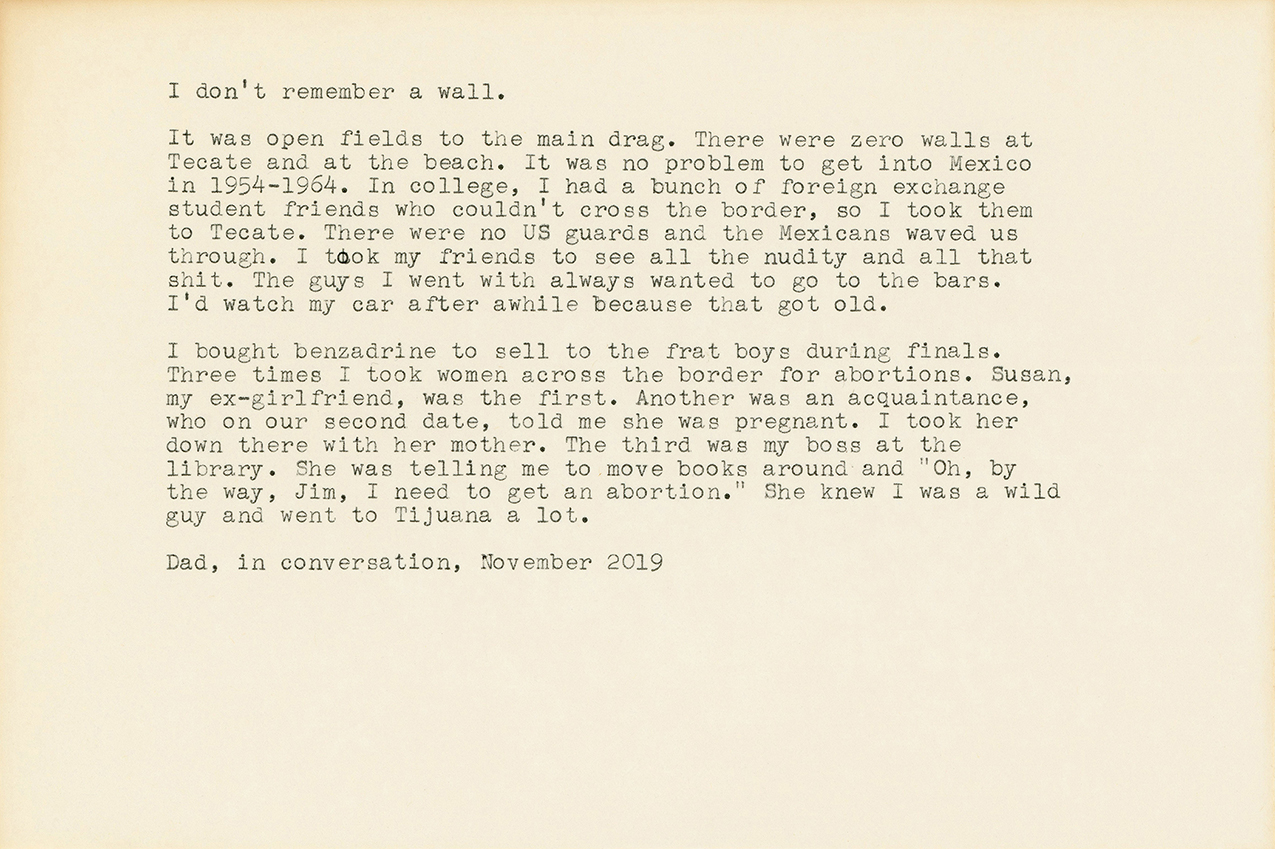

I don’t remember a wall.

It was open fields to the main drag. There were zero walls at Tecate and at the beach. It was no problem to get into Mexico in 1954-1964. In college, I had a bunch of foreign exchange student friends who couldn’t cross the border, so I took them to Tecate. There were no US guards and the Mexicans waved us through. I took my friends to see all the nudity and all that shit. The guys I went with always wanted to go to the bars. I’d watch my car after awhile because that got old.

I bought benzadrine to sell to the frat boys during finals. Three times I took women across the border for abortions. Susan, my ex-girlfriend, was the first. Another was an aquaintence, who on our second date, told me she was pregnant. I took her down there with her mother. The third was my boss at the library. She was telling me to move books around and “Oh, by the way, Jim, I need to get an abortion.” She knew I was a wild guy and went to Tijuana a lot.

Dad, in conversation, November 2019

Click image to read text

I Don’t Remember a Wall, Dad in Conversation

2019–2020

Archival pigment print

13″ × 19″

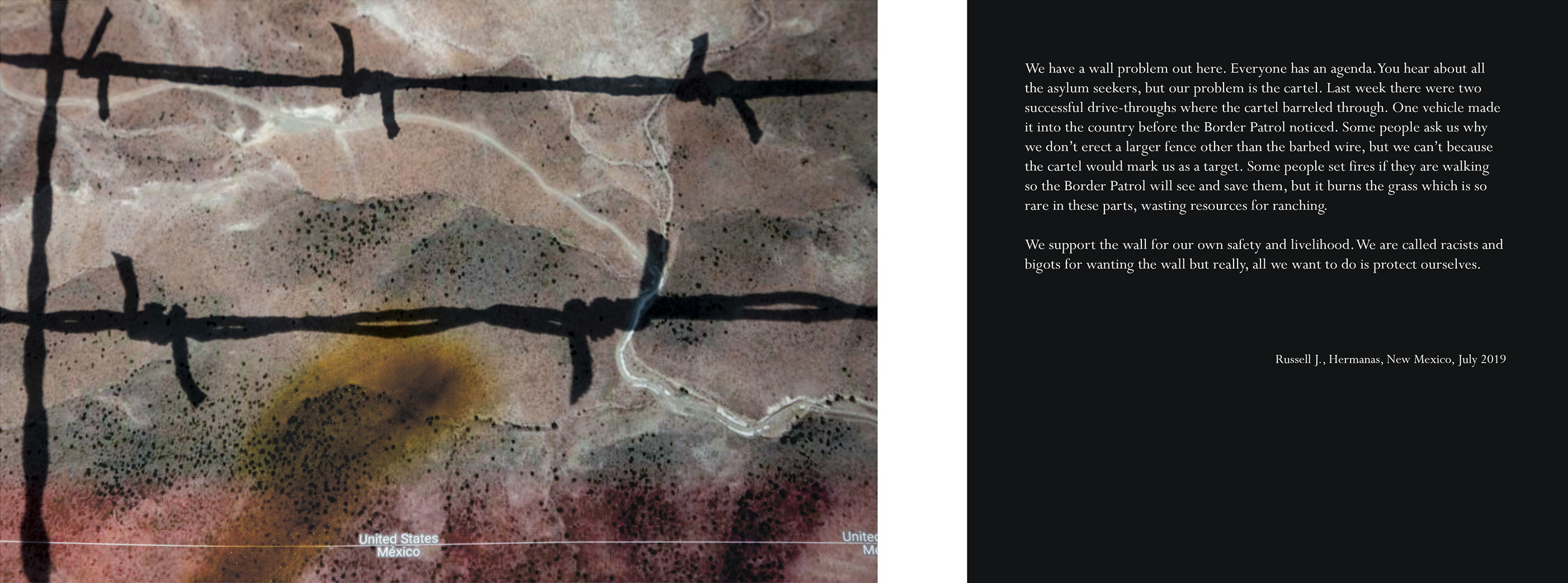

We have a wall problem out here. Everyone has an agenda. You hear about all the asylum seekers, but our problem is the cartel. Last week there were two successful drive-throughs where the cartel barreled through. One vehicle made it into the country before the Border Patrol noticed. Some people ask us why we don’t erect a larger fence other than the barbed wire, but we can’t because the cartel would mark us as a target. Some people set fires if they are walking so the Border Patrol will see and save them, but it burns the grass which is so rare in these parts, wasting resources for ranching.

We support the wall for our own safety and livelihood. We are called racists and bigots for wanting the wall but really, all we want to do is protect ourselves.

Russell J., Hermanas, New Mexico, July 2019

Click image to read text

Russell J., Hermanas, New Mexico, July 2019

2019–2020

Archival pigment prints

13″ × 19″ and 12″ × 12″

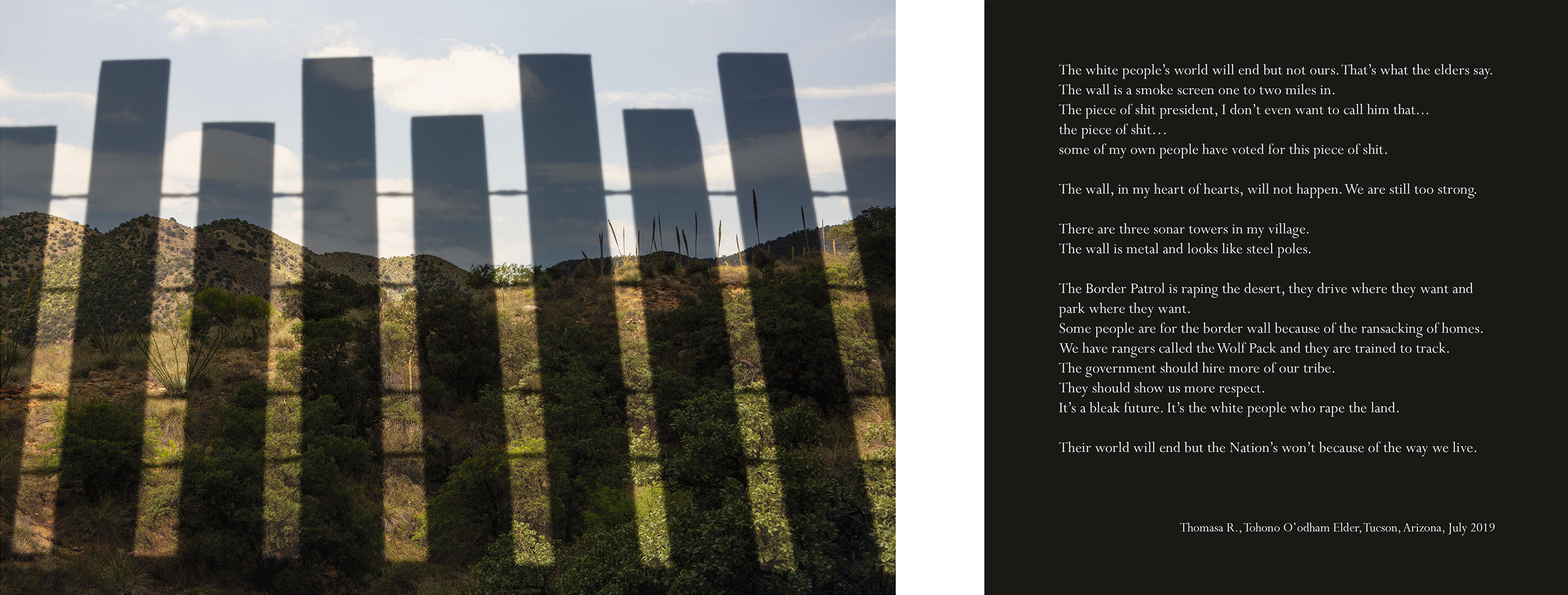

The white people’s world will end but not ours. That’s what the elders say. The wall is a smoke screen one to two miles in. The piece of shit president, I don’t even want to call him that… the piece of shit… some of my own people have voted for this piece of shit.

The wall, in my heart of hearts, will not happen. We are still too strong.

There are three sonar towers in my village. The wall is metal and looks like steel poles.

The Border Patrol is raping the desert, they drive where they want and park where they want. Some people are for the border wall because of the ransacking of homes. We have rangers called the Wolf Pack and they are trained to track. The government should hire more of our tribe. They should show us more respect. It’s a bleak future. It’s the white people who rape the land.

Their world will end but the Nation’s won’t because of the way we live.

Thomasa R., Tohono O’odham Elder, Tucson, Arizona, July 2019

Click image to read text

Thomasa R., Tohono O’odham Elder, Tucson Arizona, July 2019

2019–2020

Archival pigment prints

13″ × 19″ and 12″ × 12″

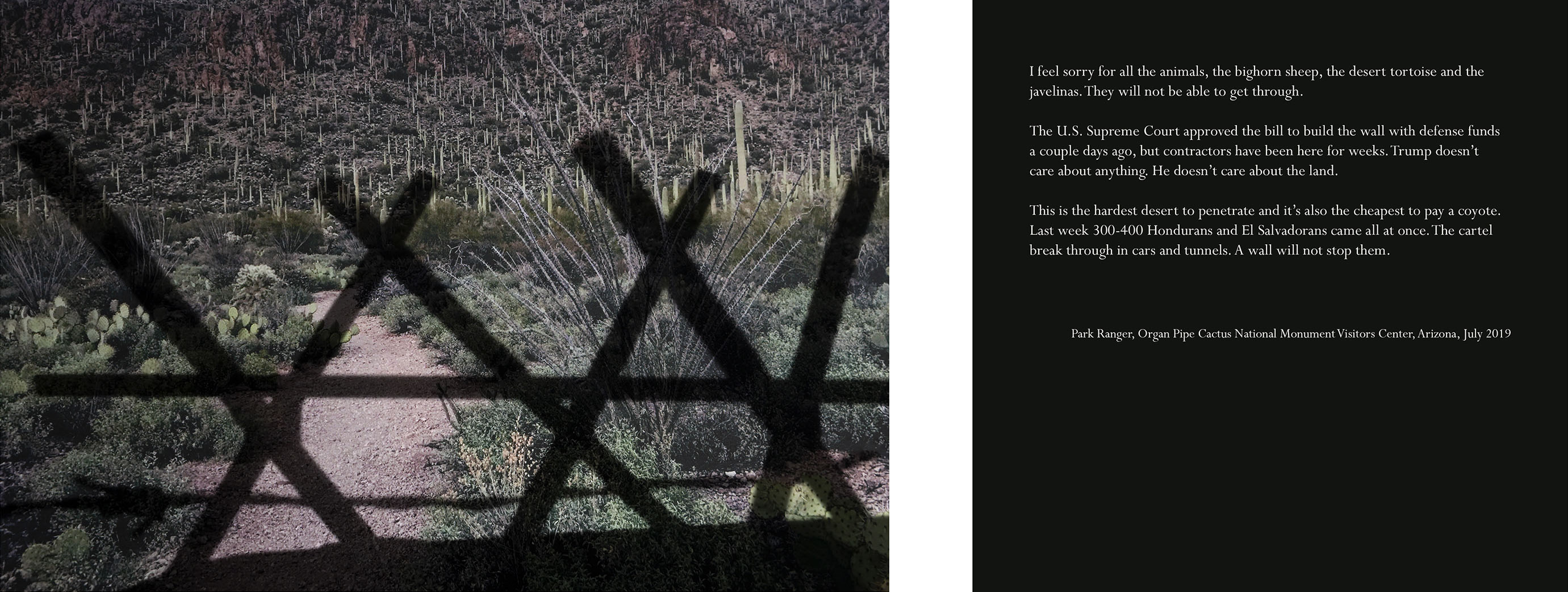

I feel sorry for all the animals, the bighorn sheep, the desert tortoise and the javelinas. They will not be able to get through.

The U.S. Supreme Court approved the bill to build the wall with defense funds a couple days ago, but contractors have been here for weeks. Trump doesn’t care about anything. He doesn’t care about the land.

This is the hardest desert to penetrate and it’s also the cheapest to pay a coyote. Last week 300-400 Hondurans and El Salvadorans came all at once. The cartel break through in cars and tunnels. A wall will not stop them.

Park Ranger, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument Visitors Center, Arizona, July 2019

Click image to read text

Park Ranger, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument Visitors Center, Arizona, July 2019

2019–2020

Archival pigment prints

13″ × 19″ and 12″ × 12″

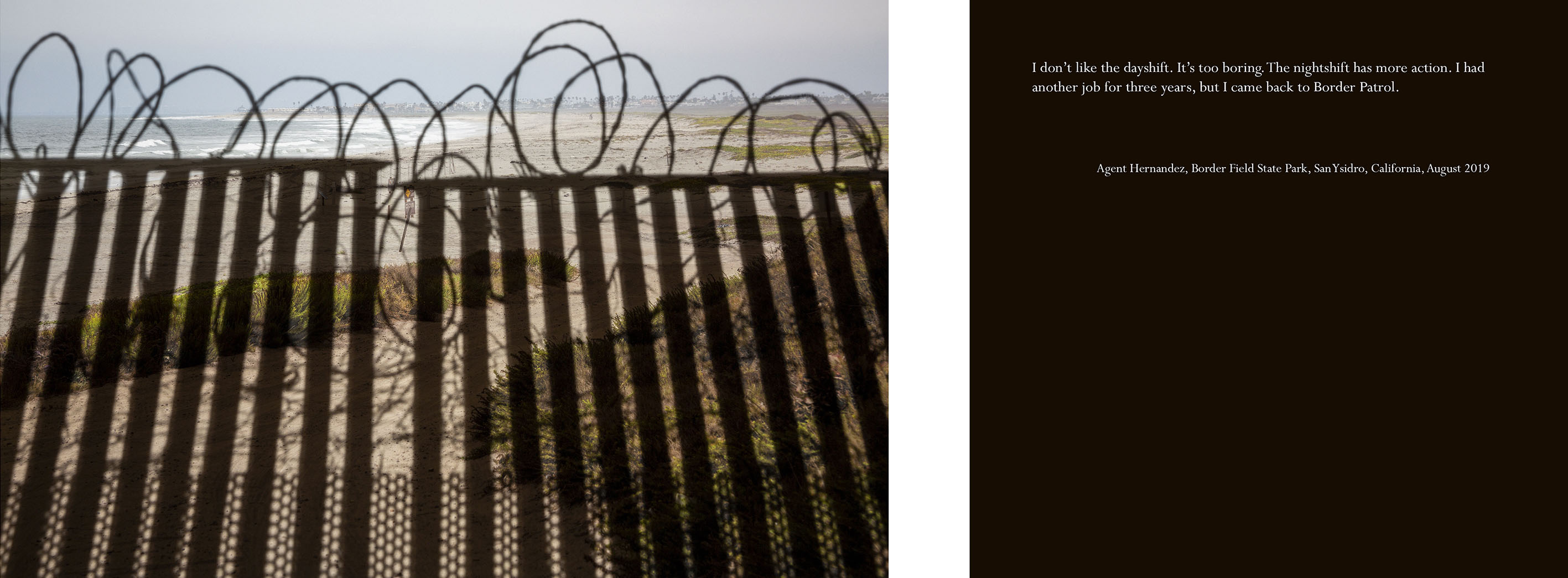

I don’t like the dayshift. It’s too boring. The nightshift has more action. I had another job for three years, but I came back to Border Patrol.

Agent Hernandez, Border Field State Park, San Ysidro, California, August 2019

Click image to read text

Agent Hernandez, Border Field State Park, San Ysidro, California, August 2019

2019–2020

Archival pigment prints

13″ × 19″ and 12″ × 12″