I am sitting in a bar somewhere with a few friends and people I’ve just met. Their eyes are glittering with laughter after I tell them about growing up with a dad with a public and private English accent. About how at work in his crisp white doctor’s coat he spoke in a kind and friendly, all American way. How he is loved by everyone for his easygoing conversations and humor, his agility with learning languages like Urdu and Tagalog from staff that disappeared as soon as he got home.

At home, Sudan T.V. is blaring in the background with people dancing around whatever really needs to be said because people are way too polite to each other for no damn reason. That is the country where I came from but never belonged. I do not mention to anyone afterwards that I have been living in exile since I was eight. I excuse myself to the restroom and as I’m washing my hands and looking at my reflection, I hear my father’s private Arab-English sputtering from the faucet hissing you think they will clap for you? to hell with you. I order a new drink and decide to sit back and listen in case his voice returns to chase me home.

![]()

For Mother’s Day, our teacher asked us to write poems to read on stage for them after they had dinner. It took the effort of four other classmates and me to push the velvet curtain far enough to one side to get a peeking view of all the tables set up in our middle school gym. Piled against each other we took turns pointing out our moms. When I found mine, dressed in a colorful traditional tobe, they all asked me if I was adopted and I started to cry and refused to read my poem. She came backstage and shook me by the shoulders straightening my shirt and warned me in a language my teacher couldn’t understand not to embarrass myself that everyone would be watching. So I got on stage and read my poem to someone make believe in the crowd.

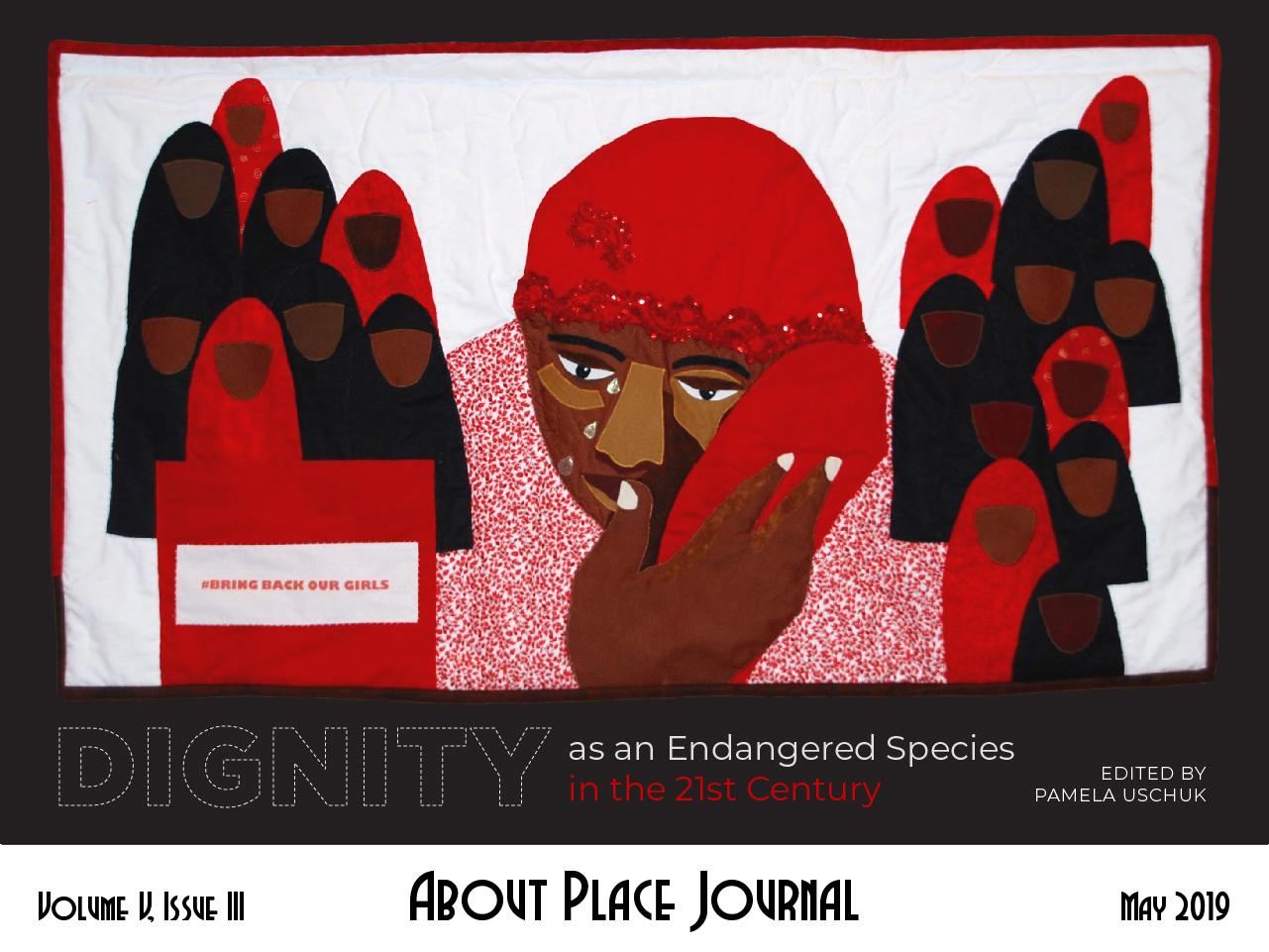

![]()

It’s summer and I’m at a friend’s house drinking horchata. This creamy tiger nut milk concoction that makes me ramble and nostalgic. My friend’s mom asks to see photos of my family and I show her pictures of my parents in the early seventies before they met each other, before any of us existed. She marvels at how stunning they were in their youth. Then I show her pictures of my siblings.

Only I know that every photo is at least a decade old. That we are now all very different people, but that I was the first to leave. You must miss them she says and I say of course out loud in Spanish, “¡Por supuesto!” Hear them arguing all at once in my mind as I tuck them back into a folded pocket in my wallet, repeating to myself طبعاً, φυσικά, tabii ki, bien sûr, certo. Of course we miss what we choose to remember.

![]()

At the airport, I am interrogated by three men. One asks in broken English how long I’ve been here, the other scans my passport and stares me down. The third is having lunch and typing some kind of report. I am imagining the measurements being taken in a separate room, with all this information. Wait for a sheet of double-glazed shatterproof glass, 178 cm fitted stainless steel frame to arrive through the door. For him to stop talking, for that pin to trap me

forever

in one place.

I have waited my entire life to come out of this.

My entire life to fly away.