Winter sky gray light. Ancient Cemetery in Yarmouth, iron front gate open as usual. A man runs Ancient Way to Center Street, and rounds the corner, loping down Winter. Head turned toward the cemetery so long, I wondered if he might see me. Solitary in these hills of stones. My family cemetery. I have a stone here myself, waiting.

Too cold to walk. I drive my old green jeep on the sand paths, look for a stone for Frances W. Bray. A neighborhood surrounds the cemetery on all sides, streets quiet. Frances’ death on November 6, 1816 was a catalyst. I want to see the ground where all of this began.

Lot 398, Section C. Unfamiliar with Lots and Sections, I drive down the path closest to me. At the end, a crossroads. Put my gloves on. Hands icy on the wheel. To my left, a large family stone: BRAY.

I’d come in Center Street, through the iron gates. Between Ancient and Winter. Frances is in the center front of the cemetery, 14th grave in from the front gate. She’s not on any of the cemetery roads. You have to walk through grass, graves. Right in the middle. Rectangle of brown grass in front of her. I’m surprised she was only a child, two years old.

Frances died in the Year Without Summer. A volcano erupted on an island, killing thousands of people. Ash blocked the sun, and the temperature dropped all over the world. On June 6th, a foot of snow fell. The bay full of ice floes.

She has family on both sides of her grave. Frances the first to die, has her own lot. One grave behind Frances, separating her from Hannah Studley’s grave, Silvanus’ wife, who died July 22, 1825. Nine years after Frances.

Did William Bray notice turned earth first? Or did Silvanus Studley see new graves near Hannah’s stone? Was the ground still frozen? Was it Christmas, when Bray or Studley brought wreaths, flowers? In early November it had still been possible to dig a grave. Almost as warm as the month of May. But November 19th, a large flock of geese flew over, headed south. Winter coming. On the 22nd, snow fell. Canal closed with ice.

In the winter of 1826, when Bray and Studley found new bodies near the graves of Frances and Hannah, it was cold. Low of minus 12. Ancient Cemetery is in Yarmouth Port, Yarmouth originally Mattacheese, Indian Town. The 22 acres of Ancient Cemetery, this whole town, all belonged to the Wampanoags. Since the beginning of time.

Whose bodies were buried near Frances and Hannah? When? What made Bray and Studley notice? Mind? So obsessed that they called a vote of the Selectman? The leafless black tree, the giant pines in the southeast corner stretch their arms.

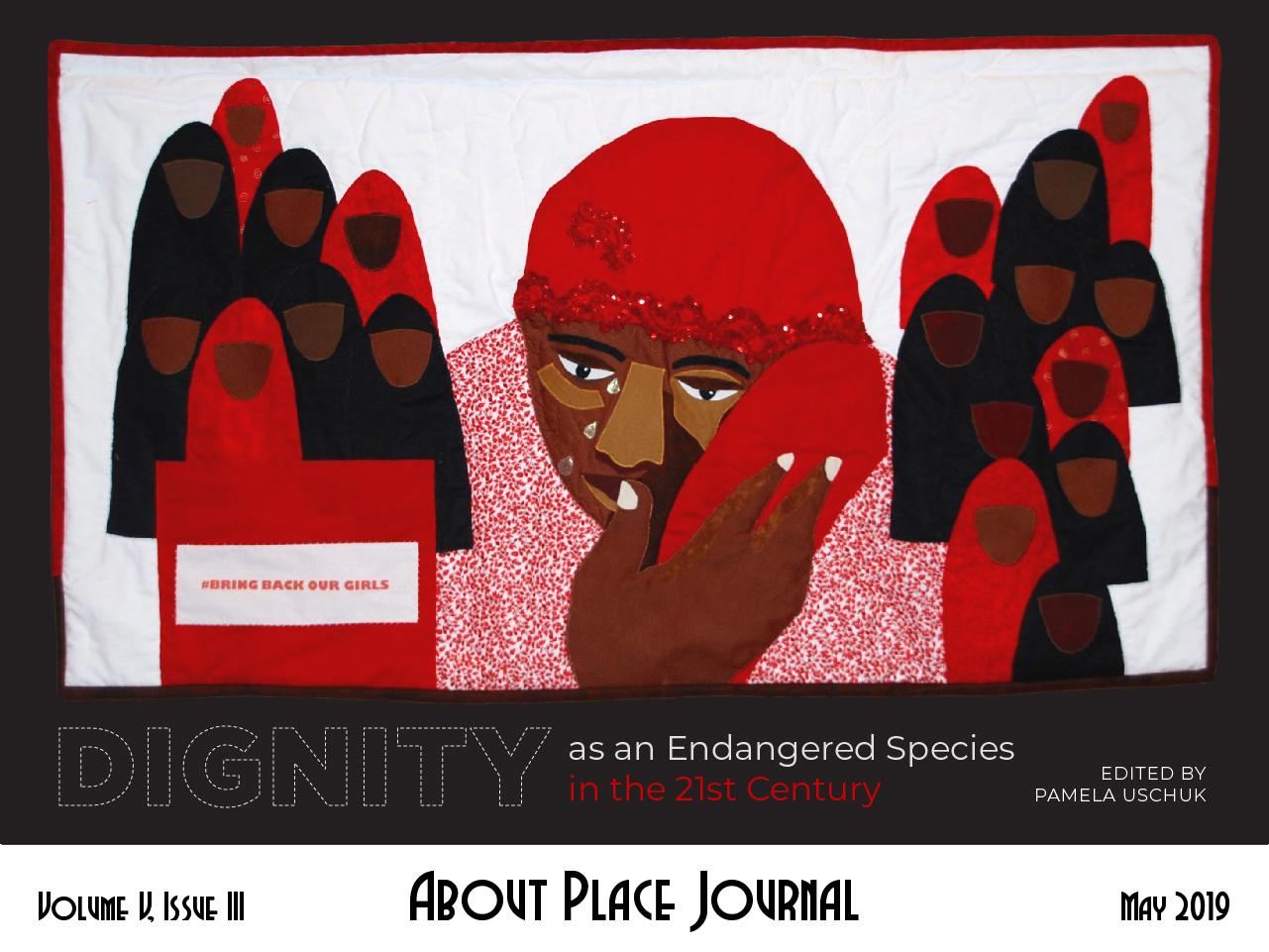

This year, at Thanksgiving, I found two small pumpkins and two round yellow squash in the center of the empty southeast corner: patchy brown grass, little haze of green, sand. Someone else knows. Someone saying I remember. The removal of the bodies of people of color. Reburial in unmarked graves.

*

In 1713, the town had set aside land from Long Pond to Bass River for Pawkunnawkut Indians of the Wampanoag tribe. In perpetuity. Thomas Greenough, my fifth great-grandfather, and the last surviving Wampanoag Indian in South Yarmouth, Massachusetts, was born in Yarmouth in 1747. Then the Wampanoags in this town died. Most of smallpox. Except Thomas Greenough.

A vote was taken for the cost the Wampanoags incurred for their smallpox care. It was paid by the town, and all of the Indians effects were “sold to pay this charge.” The town sold their land, and said they reserved a piece for Thomas Greenough, “a survivor.”

Jane Freeman, Thomas Greenough’s wife, and my fifth great-grandmother, died March 3, 1826. Twenty-one years before her husband. As a white woman married to a Wampanoag, would she have been buried with the Wampanoags on the shore of Bass River? It was Bass River reservation land, but it had been “sold.” When the salt works were proposed to be built here, where Wampanoags had long been buried, the bodies were disinterred. Reburied on a hillside near Long Pond. The street is Indian Memorial Drive. It’s marked with boulders now, inscribed with the following:

the last native Indians

of Yarmouth”

Long Pond also an ancient burial ground for the Indians. Hills fall away to the wide pond, trees my mother ran through as a child. A bright place. Where my great-aunt and her sisters swam. Maybe someone brought Thomas Greenough’s body here. And Jane’s. Grief could move their bodies. Yarmouth is less than 7 miles across, from Bass River and the ocean to the bay. From Bass River, head inland one and a half miles. A little to the right is Long Pond.

Where are their six children buried: John, Susana, Phebe, Thomas, Jinne, and Salle? Susana died Oct 21, 1825, just before people of color were removed from their graves in May of the following year. Susana was married to William Brooks, and had seven children. What about “Child” Brooks born in 1795 who didn’t live long enough to have a name? Are Susana’s seven children buried with her? Are they all here under my feet?

The same year Deborah and John Greenough’s daughter Eliza was born, Deborah gave birth to another child, not named. Deborah died on October 22, 1825. She’s white. Deborah died almost simultaneously with Susana. Are Deborah’s children buried with her? Her child died four days later on October 26, 1825. Were their bodies dug up? Reburied in unmarked graves? Is Deborah buried with her four-day-old child? I keep listening for children.

*

It’s hard to prosecute the dead. Thomas Greenough the only survivor. From a distance, smallpox looks like skin embroidered with pearls, no space in between. Blisters like bubble wrap. Only the eyes untouched, unless there’s bleeding. I don’t know what it looks like when it’s the people beside you. Everyone you know.

One disease after another, until an outbreak of smallpox killed every remaining full-blooded Wampanoag, except him. Bass River land taken in 1770 by a Writ of Ejectment. The last teepee gone. He became a self-educated lawyer, kept calling on the Selectman, asking for his land back. Bray and Studley were Selectmen.

Where he’s buried, no one knows. Maybe out in the woods. Maybe the pond where he lived before the Alms House. Greenough’s Pond, named after him. Maybe his children brought his body back to Bass River, secretly buried him on his land.

*

Deborah Nickerson is John Greenough’s wife, my fourth great-grandmother. Were she and John indebted for the smallpox? Why did the town auction everything she owned? Where did she live? Her husband at sea.

*

Thomas Greenough did have a court case settled against on March 30, 1779 “for setting his house and making improvements on land that was laid down for Indian inhabitants to live upon, contrary to the directions of the Selectman.” My grandmother’s sister said Thomas was angry when the court took his land, and went to live on the pond. The pines line the road, as if everything is entrance.

A portion of Thomas Greenough’s Bass River reservation land was the Cellar House, Packet Landing. Where the boats come in. Built around 1730, the Cellar House recently fell apart from age. A history of the town said the house was “either part of the property purchased from the Native American Thomas Greenough by David Kelley in 1797,” or moved to the site afterwards. 1797? Are these numbers transposed? Thomas Greenough was legally removed from Bass River reservation land in 1779. How could he have sold the land to Kelley 18 years later?

The Edward Gifford House, “Grapevine Cottage” at 19 Union Street, also “sits on land acquired in the late 1700s by David Kelley from the Native American named Thomas Greenough.” David Kelley, a Quaker, had first moved a house onto the southern part of the Indian reservation in 1753. He and his wife Elizabeth lived there when the smallpox epidemic struck. Elizabeth made an infirmary in her front room for the Indians. Almost all of the Indians died, and that’s when the town reclaimed the Indians lands, 1778. A year before the ejectment against Thomas Greenough. Who was it that the town paid for smallpox care? The Kelleys?

*

If land had been set aside for Thomas, why did he have to fight for the reservation land in court? Why was it settled against him? Why was he ejected from the land? If the land had already been reclaimed, how could Thomas sell it? Greenough’s Pond is three hundred acres of woodland, a large pond. Did he own this land? Or was it land left open? Why did Thomas spend the rest of his life trying to get the reservation land back? Why did David Kelley’s wife nurse the Wampanaogs with smallpox? Watch them die one after another in her house?

*

In January 1826, William Bray, a shipwright, paid a call on Thomas Greenough to tell him to dig up his dead. Captain Joshua Eldridge accompanied him. Knocked on the door. Said he didn’t want the bodies of Thomas Greenough’s dead, or any bodies of people of color, so close to his dead daughter. Or to Silvanus Studley’s wife’s body.

Were there markers for the people of color, before they were dug up? If not, how did Prince and James Matthews know where to dig? Why did the stones not matter to the Matthews? Or for anyone else buried in that corner forever after? Why do only white people have a stone? A name carved in it.

*

October 1827, the Barnstable County fire destroyed almost all the deeds. The County relied on deed-holders to bring in originals to update records. Hundreds of deeds still missing. Ever since, people have been finding deeds in their attics, bringing them in only to find the land long ago changed hands. Deeds worthless. Wouldn’t Thomas Greenough have had to bring in his copy of the deed? He was 80 years old then. Living on the pond. Or David Kelley – wouldn’t he have a copy?

The Alms House was built on a big tract of land up against the marsh and the ocean. It opened in 1831, closed in 1912. Thomas Greenough died here in 1837. One large slant-roofed building is two stories. Eight windows on each side. On the bay side, another building is attached. Six windows face out. Each building has two chimneys. A third building is detached, smaller, one chimney, three windows. All around, vast treeless land. Alms House like an outpost on a frontier.

*

Bray was unsuccessful in convincing Thomas Greenough to dig up his dead. Five months later, Prince Matthews and Captain James Matthews are in charge of removing the bodies. Did they do this themselves? Hire others to dig up all the bodies of people of color and carry them to the southeast corner? In the Spring, when they dug new holes for the bodies, did the dead simply lay on the grass, faces to sky, waiting?

The Wampanoags buried their dead facing southwest, the direction their souls would travel. When the men placed the bodies in their new, unmarked graves, were the Wampanoags facing southwest?

Carved headstones and footstones are English. A native cemetery can be marked by fieldstones. Ancient Cemetery has no fieldstones in the southeast corner. It’s flat. The other lots in the southeast corner simply say “Interments”: lot 176, 173, 20, 16, 7, 25, 33, 166. Were these people named in earlier cemetery records? Before their bodies were dug up, reburied? Were those records lost in the fire? Were their names recorded when their bodies were reburied in the southeast corner? Were those records burned in the fire in Barnstable in 1827? The fire happened a year after the bodies were moved.

*

The graveyard is full of unreadable old stones – the thin white ones with names washed off, curves of ghost letters with gold/green moss, unreadable braille. Tilted stones, a few broken stones. But even unreadable, the stone is there. There’s no marker of any kind in the southeast corner. As if purposefully forgotten. Why? As if empty, as if no one were buried there still. Thomas Greenough said no. Must have said no. Standing straight as the man in the ghost photograph my grandmother showed me. He was 79 years old.

Thomas Greenough died at ninety, in the Yarmouth Alms House. No one else lived out there. The north side of town only 1½ miles long and mostly marshland. The Alms House built on a combination of salt and fresh water wetlands. Ancient salt water bogs. Vernal pools. Tidal flats. Saltmeadow cordgrass. Rushes. Almost entirely surrounded by marsh and bay. Ocean further out. In winter, the bay is covered with chunks of ice, snow. You could die in that water. There’s one narrow road in through oak and pine forests. A thick understory. Trees grow so high competing for sunlight that it’s claustrophobic. You can’t see anything but the sand road and the trees warped into a wall on either side.

The peninsula is on top of a moraine. Glacial and granite rock left over from the last ice age of 20,000 years ago. Red maple in an old cranberry bog. Blueberry in the woods, poison ivy, cranberry, and pitch pine.

Right there at the water’s edge. Salt air. Bay breeze. In another age, it might have been a resort. Though in the 18th century, the rich avoided the coast, built inland. Protection from bad weather. Almost no trees nearby. Just four on the west side. Clustered together as if planted. Common reeds and salt water cattails in the wetlands. But treelessness made the Alms House look abandoned, out there beyond the forests. Especially at night or against the early morning white sky. It operated as a farm with pasture, cattle and gardens.

Walk over Bass River Bridge to Packets Landing. Blue sky and darker blue water, thin cloud smoke. Sea and sky. You can see what’s coming. Long Pond a mile from here, inland. Very close to Packet Landing is the Quaker Meeting House. A sign, “Kelley Road” and again, the same sign on a piece of old stone. Quaker graveyard with all identical stones. Was this Thomas Greenough’s land too? Kelley Road so close to Packet Landing. Who is David Kelley? The man who bought Wampanoag land. He seemed to follow Thomas everywhere. The Quakers lived on Greenough’s Pond. They moved here, to Kelley Road, after leaving the pond.

*

The first true photograph made the year they moved the bodies. A heliographic image with an eight-hour sun exposure on a pewter plate coated with asphalt. Washed with oil of lavender and mineral spirits. The view outside: brick of a house, roof, white sky.

Just a little over two and half miles to Alms House Road from Greenough’s Pond. So when Thomas was sick (or when he was dying? How long did he wait to leave his home?) this is the distance he traveled. The house of the poor on blue-green water, yellow marsh. Bay opening up before him. Where he died.

There was a photograph. Nana, Thomas Greenough’s great-granddaughter kept a glass pitcher of pennies on her bedroom dresser. White lace circle underneath, little lake. She had photo of two Wampanoags. The man and woman stood very straight. The photo disappears. As if it never existed. No one recalls ever seeing it. A ghost image.

What would the town have done with Thomas Greenough’s body? A pauper. An Indian.

*

On July 4, 1826, Former US Presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Adams both die on the 50th Anniversary of the signing of the United States Declaration of Independence. Before he died, Jefferson wrote: All eyes are opened, or opening, to the rights of man. Nearly two hundred years before two new flowering trees appear in the southeast corner of Ancient Cemetery. Ropes hold each one steady, on both sides like arms. Saplings. The new trees, steadied and tied to the ground. Dirt mounded around each, as around a fresh grave. A diagonal cut in the green-brown grass, sand underneath, runs tree to tree. The cemetery plan still leaves the whole southeast section of the cemetery vacant and has the word “unknown” written in it.

The Wampanoags had a church in an apocalyptic time. In between Thomas Greenough’s marriage and his death, the smallpox epidemic, in which all the other tribal members died. On Martha’s Vineyard, a church still stands, Mayhew Chapel. I took the ferry from Falmouth. The chapel has glass windows on both sides. White pews. Here, they’d quiz the teachers, ask them to explain mysteries in the Bible. Have it make sense. The building so small, they were packed inside the one room, peppering the minister with questions: How do we rise from the dead? Have I risen?

There was another path on the opposite side of the chapel, a U that leads to a root cellar, a stone hideout empty and dark. Rain. I walked back to the front door of the chapel. Four locks on the door. Inside: twelve white pews painted hymnal red on the top edges. Windows on one side shuttered, garnet carpet with little stars. Wooden altar, lace edge. Paint peeling from the ceiling above one window. It could be a room of gold leaves.

I stood on the heavy flat stone, and saw a triangle of paper sticking out from the side of the door. As if someone were passing a note to me. When I touched the edge, it folded out and open, like a fan, but still wedged in the door. It’s yellowed. Someone had written: Come In.