For all those blasting by at sixty-something

on that two-lane to Scio, she’d have been

a chance look to the left as their chrome

flashed—slight, gray-haired woman

sitting in the front window of a small house,

head bowed to the pattern

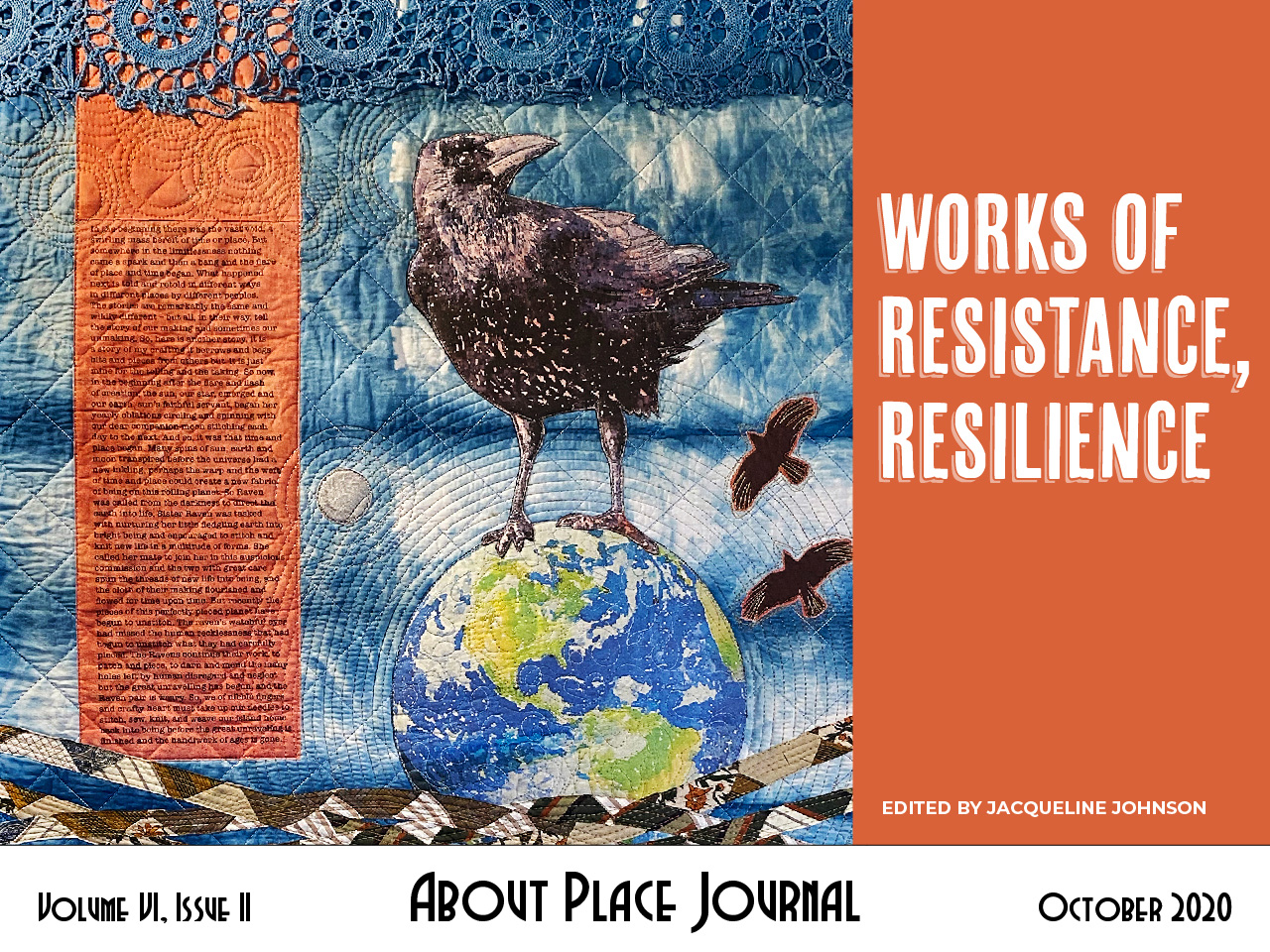

she was winding her yarn through. On one side,

a box her caregivers kept dropping

spools of all colors into, and on the other, another

filling for twelve years with doilies. No longer able

to sow her garden with rows of corn and beans,

all through her nineties, every day but Sabbath,

there she sat, sometimes getting a honk

and wave. Any who stopped left with stacks

of doilies balanced in their arms to keep

and to pass on to friends or neighbors.

No one asked her to make them,

nor did anyone ever say, Love that much,

like light greened by leaves and streams

interlaced, Love. Any in need, which was all,

always, she took into her wiry arms

and squeezed. I just love you so much!

She had no curses to give for a life of working

fuel pumps and fields, raising her two

red-haired boys, or even the time Charlie in a tractor

loaded with carrots backed over her foot.

No one knows how many doilies she made.

As long as breath moved blood and bone,

she wove the way she prayed. From Marion

to Harrisburg, there must be thousands

stuffed into cupboards. From one person

to the next, into hospice homes and through

churches, they made their way around the world,

one even pinned to a wall in Turkey, says Loyd.

Of the many I have, I’ve never put one to use

to hold a hot plate or vase, like this one,

this bicolored hexagon of triangles

making green and violet stars in my hands.

Of all the strands my great aunt left, I’m one

who can’t build or wire the way my cousins can.

I remember, though, resting my hand

on her head as she sits in rainy light, threading

my fingers through her hair like mist

as wisps of her grace thread through this.