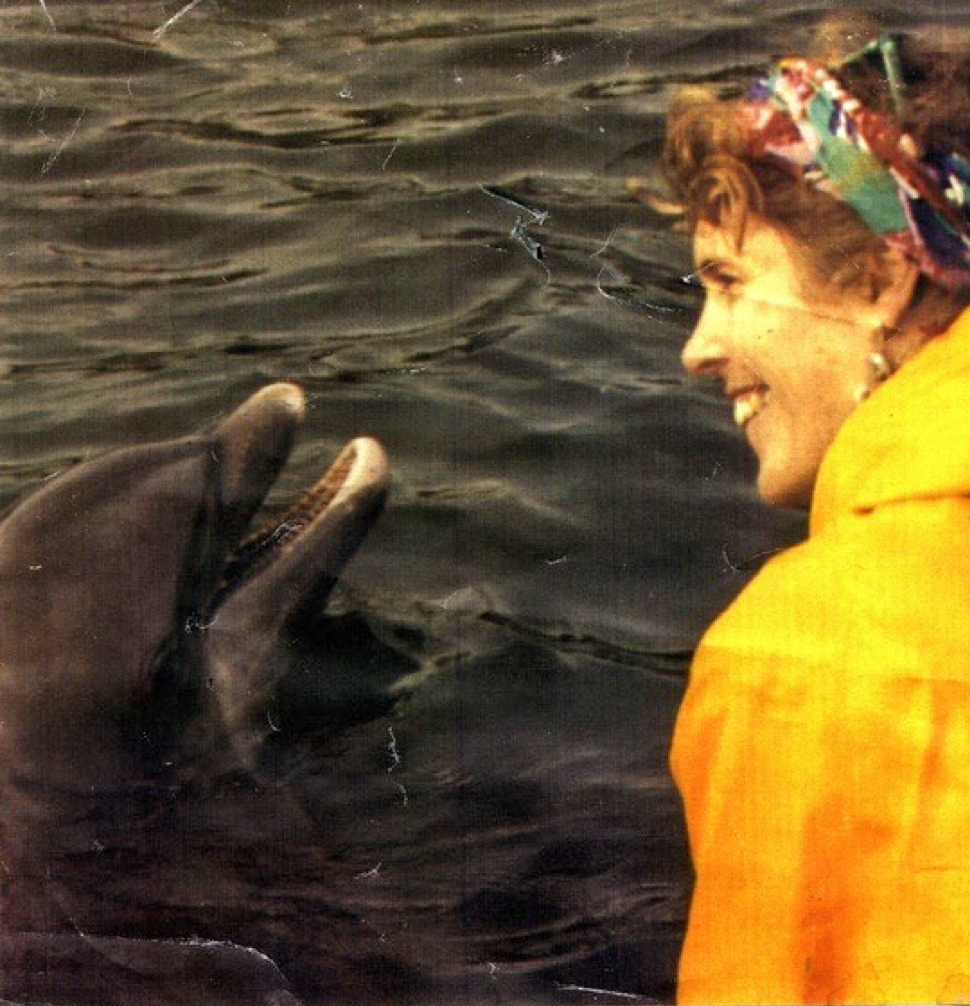

It’s not only women who benefit from strong sisterhoods. Women scientists are discovering that in many other species, sisterhood is what assures stability and survival of all. As a National Geographic author, I’ve encountered wild dolphins and whales worldwide. We have much to learn from these matriarchs and their complex sisterhoods, whose primary focus is not on competition, but on communication and cooperatively nurturing next generations.

While on a humpback whale research trip to Hawaii I kayaked into a warm-water bay and was suddenly surrounded by a wild pod of sleek spinner dolphins, including mother-calf duos accompanied by babysitting aunts and sisters.

“We’re in the middle of their nursery pod,” our naturalist guide whispered as we paddled slowly through turquoise waters.

Six dorsal fins swam close behind me, their twoosh, twoosh exhalations like musical, synchronized sighs. Thirty or so spinners swam close, circling me. At the sight of so many wild dolphins, I leaned over in awe—and promptly capsized. Plunged underwater, I heard that familiar high-pitched click and whirr that sounds like a cross between a Geiger counter and a rusty door. I floated, holding my breath as the nursery pod circled me.

The dolphins always surprise me with their tenderness. I tried to synchronize my breathing with the dolphins. Several spinners leaped up, somersaulting, and then dove back into the sea, their wake splashing over me. I attempted my human version of a dolphin signature whistle, complete with rapid-fire gurgles and bleeps. It seemed to amuse and interest the nursery pod because they all suddenly cruised by my face closer in a dazzling display of acrobatic dolphin dance.

Imagine dozens of dolphins speeding by in a blur of silver and gray skin, ultrasound, and curve of fin, streaking past, in one breath, as if one body. Inside my body their speed and sound registers like a trillion ricochets, tiny vibrations echoing off my ribs, within each lobe of my lungs, and spinning inside my labyrinthine brain like new synapses.

Then I was alone for a moment as I drifted through the depths. It is always these meditative underwater moments that the dolphins seem most to cherish in their human companions. Suddenly I saw out of the corner of each eye, three dolphins flanking both sides of me and then several tiny dorsal fins—newborns being guarded by the nursery pod. I was accepted inside their pod, surrounded by fast spinners who slowed to accompany my pace. They kept me in their exact center for what seemed an hour. It was only then I understood what it feels like to be fully adopted into the deep, welcoming sisterhood of dolphins.

I am pod, I felt, with no sense of my single self. I belong.

Women Scientists in the Field

As more female scientists, in the footsteps of Jane Goodall, enter the field of animal studies, this female bonding in animals as diverse as chimpanzees, elephants, hyenas, lions, baboons, and dolphins, is yielding fascinating insights into the vital role females play in animal societies. In the wild, dolphin pods are highly socialized groups in which complex female bonding assures the well-being and nurturance not only of the young, but also the entire pod.

Celebrated dolphin researcher Dr. Denise Herzing, author of Dolphin Diaries: My 25 Years with Spotted Dolphins in the Bahamas, has focused intently on the female relationships in one pod’s generations of over 75 dolphins. As a result, these wild Atlantic spotted dolphins have accepted and socialized her into their pod, allowing her access and intimacy unusual in cetacean studies.

Herzing cites two female dolphins in particular as examples of evolving sisterhood. Rosemole, Little Gash, and Mugsy were companions from infancy, raised under the close watch of their mothers and the elder females, who make up an essential element of all dolphin pods. Almost inseparable, all three females found their relationship shifting when both Rosemole and Mugsy became pregnant. They bonded with other pregnant and mothering dolphins, shifting alliances away from Little Gash, their former playmate. Rosemole and Mugsy were busy participating in the nurturing of newborns.

Not only must the newborns be taught to breathe, fish, and understand the sophisticated structures of dolphin society and communication, but newborns often stay all their lives near their mothers to become helpful aunts and later elders in the pod’s highly socialized female infrastructure. The adolescent males often travel as “bachelor pods,” which keep loose contact with the female primary group. When Little Gash later got pregnant, she again resumed her sisterly bond with Rosemole and Mugsy. The three are now as loyal to the welfare and safety of their young and the whole pod as they are to one another.

In the Pacific Northwest, where I live, an orca matriarch, Granny, (whom scientists call “J2”) turned 105 in 2017. She gave birth well into her elder years and led her J Pod on long travels, sometimes as far south as Monterey, California, an 800-mile journey from their resident waters off the San Juan Islands near the border of British Columbia. When she died in 2016, Granny was celebrated as a true and dignified elder.

Orcas are the largest dolphins. Researcher Sara Heimlich-Boran notes in Killer Whales that the close sisterhood of juvenile females suggests that “same sex may be as important as age in determining relationships” and that “associations between mothers and barren females showed the most stability over time.” Because the mother-progeny bond is of primary importance, the strong alliance between barren females and mothers implies that the “relationship is one of kinship.” And kinship among aunts and sisters and mothers is centered on cooperation and caretaking.

What might happen in our own species if we modeled our own human societies on lessons learned from the sisterhood of animals? Would we thrive in a more matrilineal culture that values communication more than conquest? Would we focus on keeping our habitat sustainable for future generations—both animal and human? ~