a literary journal published by the Black Earth Institute dedicated to re-forging the links between art and spirit, earth and society

They Do Not All Sound Alike:

Sampling Kathleen Cleaver, Assata Shakur, and Angela Davis

Originally posted on Sounding Out! The Sound Studies Blog

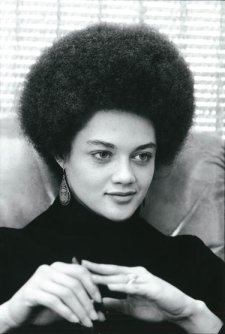

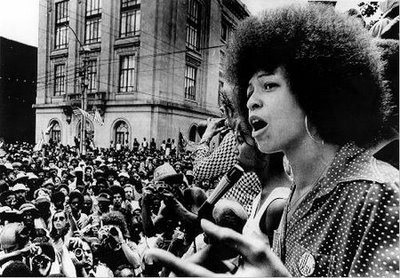

When underground hip-hop artist P. Blackk released Blackk Friday (2011), several reviewers insisted that he sampled political activist Angela Davis. Oddly enough, one of the reviews from The Meara Blog, featured the video for “Brainz,” the song in question–and the video clearly showed that the sampled track was in fact not Davis but activist and lawyer Kathleen Cleaver. Why the automatic assumption that any black woman sampled from the 1960s is Davis? Why the collapsing and erasure of so many distinct and powerful voices?

Davis, Cleaver, and Assata Shakur are arguably the three most iconic women of the Black Power Movement, but they largely go unrecognized in mainstream history. Erasure by omission represents how many historical sources are resistant to identifying their specific contributions to grassroots organizing, intellectual life, and politics, while the male leadership of the Black Power Movement is often mentioned by name. So, the inclusion of Davis, Cleaver, and Shakur in songs by hip hop artists P. Blackk, John Forté, and Common simultaneously amplifies the distinctiveness of their voices while signaling conscious choices by younger male artists to align themselves with the political thinking espoused by these radical women in politically-rooted, layered tracks–even as these samples inadvertently reveal the mainstream public’s tendency to treat black femaleactivists as interchangeable. Both in their moment and in its echoes, these women resist being grouped into an amorphous group of misconstrued black people, and these tracks highlight that.

In “Brainz,” P. Blackk samples a 1968 speech by Cleaver. In the track, the basic bassline reverbs beneath the emcee’s repeated hook. He begins the song with the “huh” sound that many emcees use to amplify enthusiasm, start rhyming, and alert whomever is listening that the words are about to arrive. Blackk repeats certain phrases and utilizes internal rhyme as he makes observations about the choices people should make to care for themselves, their children, and their communities. The most original slant rhyme emerges in the second of two verses, replicated here:

It’s funny how we love chains and whips

when we were bound by em.

and we hate rock’n’roll and it was found by us.

You can’t hate what’s beautiful. I’m black and I’m proud,

but that ain’t got nothing to do with my pants sagging down.

Society is pimping you.

I’m just a man who’s a little more sensible.

I used to be invisible, now I’m invincible.

Not the stereotypical,

and I’m doing my thing in a game with no principles.

Knowledge and power, all I need, yeah, that’ll do.

The difference between me and my peers is gratitude.

Younguns is dumb too and too cool,

but it’s uncool living in a city that’s gun-ruled.

Here, P. Blackk most closely echoes how Cleaver expresses a sense of embracing and affirming black beauty while still acknowledging flawed educational systems, materialism, the origin of rock music, intergenerational disconnects, and gun violence. As a member of the Black Panther Party, wife of Eldridge Cleaver, attorney and professor, Cleaver has been a spokesperson for African American struggles. When the chorus simply repeats “real n-gga wit a brain,” P. Blackk is claiming the term that is still an affront to middle class people reaching for the civility of assimilation. He is insisting that some people are afraid of their intelligence and growing awareness as marginalized people and what actions that might entail. This fear of a nascent threat was at the root of resistance towards the slogan “Black is Beautiful” in the 1960s.

The Cleaver sample comes at the end of “Brainz,” and in the music video appears in its entirety on a projection screen and against P. Blackk himself, decked in a white shirt and bow tie, as he “lectures” students in a darkened classroom. As different black historical figures, including the likes of Marcus Garvey, Rosa Parks, Angela Davis, Ralph Abernathy, George Jackson, and James Baldwin, are projected on the screen behind Blackk, the instrumental audibly drops much lower so the only voice heard is Cleaver’s.

(Cue to 3:05 for Kathleen Cleaver)

The footage from which her sample is taken has background sound such as others talking and a chant with cadences that were often heard at black political protests; these can be faintly heard along with the audible buzz of varied speaking voices in the crowd that surrounding Cleaver. She was not onstage nor the main focal point of the larger event, but P. Blackk’s re-framing places her at its center. When one considers the position of Davis and Cleaver as esteemed and radical activists and professors, it’s not surprising that P. Blackk video positions him as an educator, like these women, to further reinforce the point of Cleaver’s words.

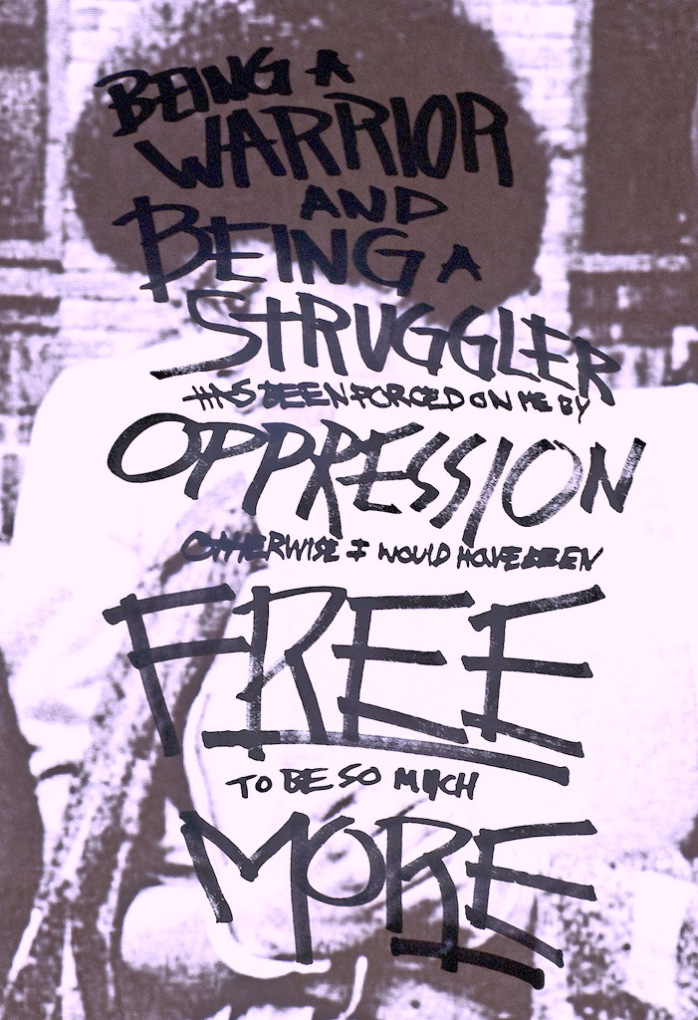

In “A Song for Assata,” from Like Water for Chocolate (2000), Common retells some of the events detailed in Assata: An Autobiography, but his sample reinforces why her activism was so important to Common and others like him. Her looped voice concludes his song, incredulously repeating the question, “You askin’ me about freedom?” In the sample Shakur explains how she knows more about what freedom is not, which is similar to a comment that Shakur made in Gloria Rolando’s documentary Eye of the Rainbow: Assata Shakur and Oya. Shakur then defines how freedom allows one to be one’s self, and the definition is faded down and the last of the soaring music rises slightly. When this fade occurs, we have a few examples of what Shakur imagines what freedom could potentially be, but it also leaves a sonic pause where listeners might contemplate how they define freedom for themselves.

The choice to fade out a sample says so much about not just the message that it (and Common) hopes to convey, but also reveals narratives that have been enforced consistently through institutions and time. I read the fade out as sonically emphasizing “the struggle,” rather than the intellectual present of an activist speaking; it limits her to the role of an representing the past. In dream hampton’s documentary Black August, Malcolm X Grassroots Movement organizer Meron Haile Selassie elucidates how women like Shakur are idolized:

Historically, the black liberation movement and actually all movements, let’s be honest, have fallen short of trying to incorporate the role of women, what women need, and how we incorporate anti-sexist theory and anti-sexist work in our general liberation movement. And when the woman that we put on the poster every single year, Assata Shakur, is someone that these artists revere and talk about yet but they’re somehow unable to see an Assata Shakur in the woman they’re dating that’s a painful realization.

In other words, even in black history and social movements, some women are canonized and celebrated and others are disregarded, which is not a far cry from the well-worn debate of using the word “b-tch” or “ho” and insisting that this namecalling does not address all women. Such overlooking and fading out is a subtler silencing of women.

John Forte’s “Drift On” works against the narrative of the fade-out in “A Song for Assata.” In “Drift On,” from his album The Water Suite (2012), Forte lyrically articulates the feeling of being distant from someone; however, it is the brief sample of a few seconds from Angela Davis that reinforces the possibility of redemption during and after confinement. Forté begins singing the hook over a guitar-like loop that functions almost like a chord, and his soft singing of the chorus contrasts with his solemn rhyming lines and the firm solemnity of Davis’ brief sample midway through the song. A little more than a minute before “Drift On” ends, Davis speaks:

many people recognize that they can refashion themselves. They can rehabilitate themselves. They can live a life of the mind.

Davis stresses the words “they,” “refashion” and the third, final “can” spoken in this sample. Her tendency to stretch and soften particular nouns and verbs in speaking is a consistent pattern in Davis’ public speech, achieved by rhetorical devices such as metanoia– the immediate restatement of a phrase–and amplification. When Davis speaks in this manner, she makes listeners pay attention to the “they” whom she refers to as intellectually capable, but it also stresses “possibility” and redemption of the self.

It is important to note that the artists sampling these iconic Black women are men. Although women such as Me’shell Ndegeocello, and Terri Lyne Carrington and Diane Reeves have sampled Angela Davis on successful records, these records were not necessarily considered hip hop, which has consistently relied on men’s voices to create a radical impression in music, like Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.” Public Enemy long relied on voices like Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr., but happens to (and with) women’s voices? Including these voices in hip hop shows that women do exist as thinkers, activists, and speakers, even if the exposure is being exercised by artists who are men.

However, each song extends the narrative of each woman in a different manner than they constructed for themselves. P. Blackk stops admonishing, advising, and insisting on pragmatic Afrocentrism so he can to listen to Cleaver explain why black beauty was finally being embraced in the 1960s. Cleaver, in her 1968 speech, eschews white standards of beauty to embrace herself, which P. Blackk uses to connect self-hatred in the past and self-destructive behavior in the present. Common ends “A Song for Assata” with Shakur so she can share some of her thoughts on freedom after the song relates major events from her life based on details and paraphrased lines from poems in Assata: An Autobiography. Forté uses the sample of Angela Davis to further a narrative that reveals how the prison industrial complex diminishes perceptions of the humanity and the intellectual capacity of prisoners in “Drift On.”

These three hip hop songs align with a continuum of specific radical women during a time when there are few women getting consistent recognition in the genre of hip hop music, so it marks a curious point of departure where women can be part of conversations in a musical genre where they are not frequently prominent as vocalists. This sampling practice also places men and women in conversation–activists, artists, and listeners–in a manner that reflects strength, certainty, and a sense of coming together with specific political ideas in a manner that, importantly, does not erase intellectual, or sonic, difference.

Tara Betts is the author of the poetry collection Arc and Hue, a Ph.D. candidate at Binghamton University, and a Cave Canem fellow. Tara’s poetry also appeared in Essence, Bum Rush the Page, Saul Williams’ CHORUS: A Literary Mixtape, VILLANELLES, both Spoken Word Revolution anthologies, and A Face to Meet the Faces: An Anthology of Contemporary Persona Poetry. Her research interests include African American literature, poetry, creative writing pedagogy, and most recently sound studies. In the 1990s, she co-founded and co-hosted WLUW 88.7FM’s “The Hip Hop Project” at Loyola University while writing for underground hip hop magazines, Black Radio Exclusive, The Source, and XXL. She is co-editor of Bop, Strut, and Dance, an anthology of Bop poems with Afaa M. Weaver.

©2026 Black Earth Institute. All rights reserved. | ISSN# 2327-784X | Site Admin