a literary journal published by the Black Earth Institute dedicated to re-forging the links between art and spirit, earth and society

Organization and Movement: The Case of the Black Panther Party

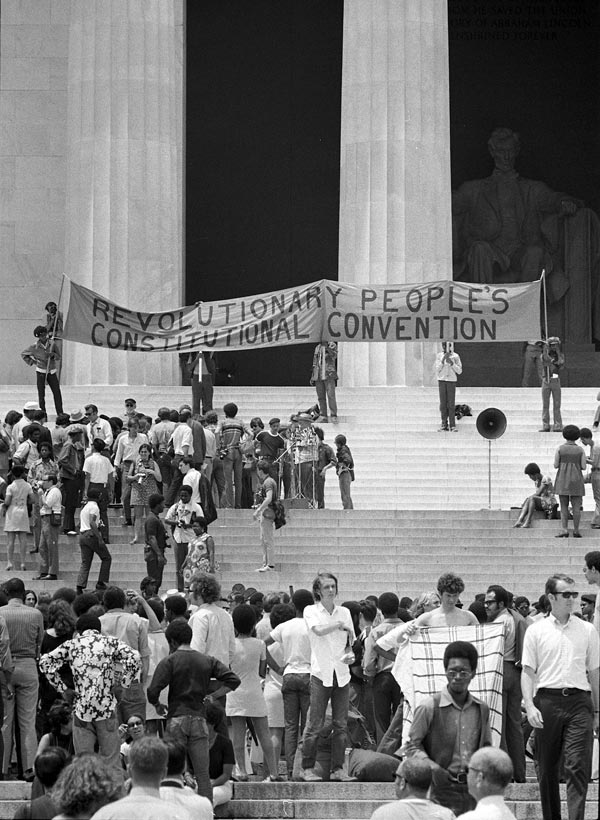

and the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention of 1970

Millions of “ordinary” people pay with their lives for the decisive events that determine the outcome of world events. Their actions and thoughts enter into most histories, however, only as objects affected by momentous decisions leaders make, not as subjects of the social world upon which decision-makers depend. Historians typically study the writings of world leaders and construct meticulously researched biographies of such figures in order to shed light on momentous events, such as the creation of constitutions. Yet the notion that “people make history,” long ago incorporated into the language of social scientists, seldom informs accounts of World War II, the Civil War or even many cases of social movements—grass-roots attempts to change outmoded patterns of everyday life. Take the case of the civil rights movement, for example. Biographies of Martin Luther King, Jr. or Malcolm X are the norm, not accounts of the millions who changed their lives and revolutionized society through sacrifice and struggle, transforming even Martin’s and Malcolm’s worldviews. Every child knows King’s name, but how many Americans ever heard of Fred Hampton’s assassination or know what COINTELPRO stands for? How many of us could say even one knowledgeable sentence about the massacres of students at Orangeburg, Jackson State or North Carolina A&T?

Even the movement tends to regard the ideas of its leaders, political parties and organized groups as most significant. No less than conventional historians, radical analysts often seem unable to comprehend the intelligence of crowds that embody the popular imagination. There are many reasons for this blind spot, including the ease with which accounts of leaders and organizations can be constructed compared with the difficulties one encounters when seeking to comprehend single events in the ebb and flow of sporadic gatherings of nebulous groups—precisely those incidents thought to be little more than actions by random collections of people. Sometimes pivotal events are so shrouded in mystery that historians do not even agree as to whether the events in question even took place.[1]

History seldom cooperates by providing us with clear indications of participants’ thinking during instances of “spontaneously conscious”[2] crowds. One such exceptional case is the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention (RPCC), a multicultural public gathering of between 10,000 and 15,000 people who answered the call by the Black Panther Party (BPP) and assembled in Philadelphia on the weekend of September 5, 1970. Arriving in the midst of police terror directed against the BPP, thousands of activists from around the country were determined to defend the Panthers. They also intended to redo what had been done in 1787 by this nation’s founding fathers in the city of brotherly love–to draft a new constitution providing authentic liberty and justice for all. Although seldom even mentioned in mainstream accounts, this self-understood revolutionary event came at the high point of the sixties movement in the US[3] and was arguably the most momentous event in the movement during this critical period in American history.

This essay seeks to develop an understanding of the hearts and minds of the diverse community drawn to the convention. By examining primary documents produced by the RPCC, I hope to shed light on the popular movement’s aspirations. I seek to illustrate how the intelligence of popular movements sometimes outpaces even the most visionary statements of its leading individuals and organizations by comparing these written statements with the original platform and program of the BPP drafted four long years earlier. (All these documents are appended at the end of this book.) In the tradition of using primary documents to probe the essential character of historical events, to negate more historically superficial analyses like those relying primarily upon individual biographies of Great Men and Women, I will first discuss the BPP platform (formulated by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in October of 1966) and then analyze the proposed new constitution drafted at the RPCC. Besides the primary documents of the RPCC and fragmentary accounts by a few historians and activists, I draw from my own personal experiences as a participant in the RPCC. For 30 years, I have kept a copy of the original proposals generated by the workshops that formed when the large plenary session broke down into at least ten smaller working groups. These documents convey unambiguous statements of the movement’s self-defined goals and provide an outline of a freer society. Although it has been practically forgotten by historians, the RPCC is a key to unlocking the mystery of the aspirations of the 1960s movement. The majority of my essay deals with the RPCC because so little has been written about it.[4] I hope this article encourages future work on the RPCC.

Many writers have examined the early history of the sixties, but far fewer look at the time when the movement spread beyond the upper middle-class constituencies and elite universities that gave rise to both the civil rights movement and student movement. Popular stereotypes of the sixties often end with Martin Luther King’s assassination, yet by late 1969, the movement had become so massive and radical that its early proponents did not recognize (or sometimes even support) it. In 1970, when the movement reached its apex, working-class students, countercultural youth and the urban lumpenproletariat (unemployed street people and those who supported themselves through criminal endeavors) transformed its tactics and goals. Shortly before their murders, both Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X were coming to much the same radical conclusion as that shared by the participants at the RPCC: the entire world system needs to be revolutionized in order to realize liberty and justice for all.

Part of the problem involved with historical accounts of the 1960s concerns the profound character of the rupture of social tranquility and social cohesion that occurred in the USA. Consistently uncovered in Harris polls and Yankelovich surveys, the revolutionary aspirations of millions of people in the US in 1970 constitute a significant set of data for understanding how rapidly revolutionary upsurges can emerge—and how quickly they can be dissipated. In 1970, immediately after the national student strike, polls found that more than one million students considered themselves revolutionaries.[5] The next year, a New York Times investigation found that 4 out of 10 college students (more than three million people) thought that a revolution was needed in the US.[6] While these are substantial numbers, they do not count millions more outside American universities in the ghettoes and barrios, the factories, offices and suburbs. For a brief historical moment, the movement in the US accomplished a decisive break with the established system. Unlike similar events in France in May 1968, whose discontinuity from the established society is common knowledge, the “break” in US history has been hidden. Neither revolutionary activists nor mainstream historians want to acknowledge the revolutionary stridency of that period, both preferring to promulgate more socially acceptable ideas like those of the young Martin Luther King, Jr. or the still-not-mature Malcolm X. Under these circumstances, it is understandable that the revolutionary upsurge of 1970 is quite difficult to recall thirty years later.

Elsewhere I have written that the popular imagination can best be comprehended in the actions and aspirations of millions of people during moments of crisis—general strikes, insurrections, episodes of the eros effect, and other forms of mass struggle.[7] The RPCC was one such episode, and even in apparent failure, the convention inaugurated many ideas that subsequently have become so significant that millions of people were actively involved in pursuing them. For revolutionary movements, the dialectic of defeat often allows aspects of their aspirations to be implemented by the very system they opposed.

Writing the Panther Platform and Program

No doubt individuals are products of their times, but that is not all we are, particularly when, we set out to change the world and, like Newton and Seale, have an impact far beyond what we imagined. Within a few short years of their fateful decision to organize the BPP around the platform and program they drafted in 1966, they were both locked in prison facing murder charges, and the organization they had founded exploded from a handful of members to more than 5,000. By the end of 1968, their newspaper ( The Black Panther ) sold over 100,000 copies weekly.

For 15 days they worked collaboratively to produce the platform and the program. [8] With typical self-effacing modesty, Seale insists Newton “articulated it word for word. All I made were suggestions.” After they finished distilling the wisdom of years of Africans’ yearnings for freedom, of putting into the language of the young and rising baby-boom generation their innermost dreams and the basic needs of African-Americans, they established the party. As Seale recounts:

When we got through writing the program, Huey said, “We’ve got to have some kind of structure. What do you want to be,” he asked me, “Chairman or Minister of Defense?”

“I’ll be the Minister of Defense,” Huey said, “and you’ll be the Chairman.” “That’s fine with me,” I said…With the ten-point platform and program and the two of us, the Party was officially launched on October 15, 1966, in a poverty program office in the black community in Oakland, California. [9]

At the center of their vision stood two dimensions of the legacy of Malcolm X: armed self-defense and United Nations’ attention to the plight of African-Americans. But Newton and Seale were not simply the heirs of Malcolm X’s vision; they also went further, demanding “power to determine the destiny of our Black community.” They insisted that the federal government should provide “full employment for our people,” decent housing, “fit for the shelter of human beings,” and an “end to the robbery by the white man of our Black community.” The program demanded that Black men be exempt from military service, that Black prisoners be retried by a jury of their peers, that the education system teach the “true nature of this decadent American society.” What attracted the most attention was their call for “an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of black people.” Point 7 called for “organizing black self-defense groups,” and maintained that “all black people should arm themselves for self-defense.” Continuing from the exemption of all black men from military service, point 6 stated: “We will protect ourselves from the force and violence of the racist police and the racist military, by whatever means necessary.” True to their words, Newton and Seale immediately began organizing groups of Panthers to patrol the police, and Newton’s stubborn insistence on his right to observe and criticize the police—even at the point of a gun—became legendary (or notorious, depending on one’s perspective).

Remarkable in its ability to grasp the past and make it part of the present, the Black Panther Party program resurrected neglected promises like forty acres and a mule. Nonetheless it still bears the birthmarks of the society from which it emerged. The words “man” or “men” appear no fewer than 15 times in the 10 points. Even with regard to Black prisoners, point 8 reads: “We want freedom for all black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.” The next sentence, not italicized and omitted from public summations of the 10 points in speeches, extends the demand: “We believe that all black people should be released from the many jails and prisons because they have not received a fair and impartial trial.” When composing a jury of peers that would presumably rehear the cases of these prisoners, however, reference is made to the “average reasoning man” of the black community. Similarly point 2 maintains that “…the federal government is responsible and obligated to give every man employment or a guaranteed income.” No mention is made of women’s rights to jobs.

While language indicates assumptions being made, I believe that neither the content of the program nor the actions of the BPP should be obscured or twisted by a rigid linguistic analysis. At the time the platform was written, usage of “man” for “human” was commonplace and unquestioned. Martin Luther King’s call for a “society not of the white man, not of the black man, but of man as man” or Herbert Marcuse’s book, One Dimensional Man, are examples with which one could begin. Even as Huey Newton wrote his public endorsement of women’s liberation and after sexism in the BPP was officially condemned, he continued to use “man” rather than “human.”[10] On balance, the BPP opposed sexism within its own ranks and in the larger society. That is part of what makes it so important historically. Four years after the program was written, the party took a formal position in support of women’s liberation, but even before then, as the feminist movement developed in the society at large, the BPP was transformed in its internal affairs, public statements and practical actions.[11]

The platform and program were written during the party’s Black Nationalist phase. Still to come were three more phases in the ideological evolution of the BPP: revolutionary nationalist, revolutionary internationalist, and intercommunalist. In the four years beginning in October 1966, history accomplished more than in the preceding 40 years, at least in terms of the self-understanding and status of urban, young African-Americans. It is difficult to overestimate how much the Panthers transformed young African-Americans. Under Panther influence, hardened criminals rose before 6 a.m. to serve free breakfasts to thousands of school children; drug addicts kicked their habits and worked to expel dealers from the neighborhoods; and men used to having their way with women learned to listen to and respect their female counterparts.

A keen, insightful document, the program’s third point contained an often-overlooked analogy between African-Americans and Jewish victims of the Nazis. Using the case of German reparations being paid to Israel for genocide of the Jewish people, Newton and Seale argued for reparations for African-Americans. Claiming the “Germans killed six million Jews. The American racist has taken part in the slaughter of over 50 million black people; therefore, we feel that this is a modest demand [forty acres and two mules] that we make.” No lawyer in a court of international law could make a better case based on historical precedent.

The final point both summarized the problems and offered a solution: “We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace. And as our major political objective, a United Nations-supervised plebiscite to be held throughout the black colony in which only black colonial subjects will be allowed to participate, for the purpose of determining the will of black people as to their national destiny.” The program concluded by rephrasing the declaration of independence’s insistence in 1776 on the right of revolution. Governments, it was remembered, are created to serve people, and “whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to affect their safety and happiness. With these words, Huey and Bobby had laid the groundwork for the RPCC.

Writing a New Constitution the Panther Way

Before discussing the specific documents produced by the RPCC, a few words about its context are needed. In the week before people gathered in Philadelphia, police bloodily assaulted all three Panther offices in the city, arresting every member of the Party they could find. The Panthers had not accepted their fate without a gunfight—as was their practice across the country—and three police were wounded in the shooting. Afterwards, the police forced captured Panther men to walk naked through the street while being photographed by the press. Police chief Rizzo gloated he had caught the “big, bad Black Panthers with their pants down.”[12] Publicized widely, the atmosphere created by these events was an important part of the aura of the RPCC. Philadelphia Panther member Russell Shoats recounts that in the weeks before the RPCC the Panther Central Office in Oakland made it clear to Philadelphia party members that even Huey Newton was “afraid to come to Philadelphia.” Shoats remembers that they “went on to express their opinion that the racist Philadelphia police would feel comfortable in attempting to assassinate him during the planned Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention Planning Session…” [13]

Tension and anxiety were the companions of everyone contemplating the trip to Philadelphia, particularly for Newton. Since 1967, the “Free Huey” campaign had mobilized and amalgamated diverse constituencies from around the country (and the world). Within a few years of its founding in 1966 (during most of which Newton sat in prison), the BPP became the “most influential revolutionary organization in the US.”[14] More ominously, J. Edgar Hoover labeled them the greatest threat to the internal security of the country. The FBI and local police departments massively assaulted Panther offices across the country. As police murdered Panthers, destroyed their offices, and arrested hundreds of them, a reaction against the FBI set in not only in the black community but among all minority groups, millions of college students and the radicalized counterculture–all of whom descended on Philadelphia to support the Panthers. As a global uprising in 1968 swept the planet, the Panthers were best positioned (as the most oppressed in what Che Guevara called “the belly of the beast”) to embody the global aspirations to transform the entire world system. Delegates from local black groups and from an array of organizations–the American Indian Movement, the Brown Berets, the Young Lords, I Wor Keun (an Asian-American group), Students for a Democratic Society (the national student organization with a membership of at least 30,000), the newly formed Gay Liberation Front and many feminist groups–all regarded the BPP as their inspiration and vanguard. This extraordinary alliance constituted the RPCC, and they were able to unify and develop their future direction. Most remarkable of all, this diverse assembly was able to write down their vision for a free society.

Despite the massive police actions designed to scare people away from Philadelphia, thousands came. Various estimates of the numbers exist, none of which claims to be definitive. Hilliard says there were 15,000;[15] the Panther paper used numbers ranging from 12,000 to 15,000;[16] social scientist G. Louis Heath states that the plenary sessions on September 5 and 6 attracted 5,000 to 6,000 people (of whom 25 to 40 percent were white) but doesn’t count thousands more who were outside and could not get in.[17] The New York Times declared there were 6000 people inside with another 2000 outside (about half of whom were white);[18] and the Washington Post , probably parroting the Times , later claimed 8000.[19] People came from around the country, as spontaneously assembled groups rented buses. In at least two cities, people reported that these buses were suddenly canceled without explanation, compelling people to improvise rides. Twenty-two persons from East St. Louis in a three-car caravan were arrested and charged with firearms violations, and at least one New York Panther was arrested en route to Philadelphia.[20] Organizations and delegates from Florida and North Carolina made a notable impression, as did representatives from African liberation movements, Palestine, Germany, Colombia and Brazil.[21]

When we arrived, rather than face police terror as we expected, we found the homes of African-Americans opened to us, their churches hospitable refuges and the streets alive with an erotic solidarity of a high order.[22] Signs in storefronts read “WELCOME PANTHERS” and five flags flew outside the convention center: in descending order, they were the Panther flag; the flag of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam; the green, black and red flag of black nationalism; the YIPPEE flag (green marijuana leaf on black flag); and a flag of Che Guevara. Evidently the Panthers had done a huge amount of planning for the event, as food was also provided for many people. Contrary to some accounts, armed expropriation was one tactic the BPP employed to feed everyone. Russell Shoats recounts how a 15-ton refrigerated truck with tons of frozen meats was commandeered and unloaded on the same day Panther squads robbed a bank.[23]

Some Party members were preparing and implementing the armed struggle, while others were organizing the planning session for the RPCC. On August 8 and 9, the planning group met at Howard University. Present were representatives of welfare mothers, doctors, lawyers, journalists, students, tenant farmers, greasers from Chicago, Latin Americans, high school students, gays, and concerned individuals.[24] Simultaneously, the Philadelphia black community unified in support of the convention. After the police raids Panther offices had been sealed, but people opened them back up on their own initiative. The Panther paper reported: “In North Philly, two rival gangs had made a truce…They emerged 200-300 strong and when 15 carloads of pigs drove up and asked them who gave them permission to open up the people’s office, their reply was “the people,” and the police had to eat mud rather than face the wrath of an angry armed people.”[25]

Registration On Friday and Saturday morning went off without police problems, and later on Saturday, people gathered for the plenary. Inside McGonigle Hall at Temple University where the plenary sessions took place, a vibrant and festive atmosphere prevailed. We had won. The police had been unable to stop us. As waves of people accumulated, the hall swelled to its capacity, and anticipation grew. Panther security people indicated the speakers were about to begin. Suddenly, hundreds of gay people entered the upper balcony, chanting and clapping rhythmically: “Gay, gay power to the gay, gay people! Power to the People! Black, black power to the black, black people! Gay, gay power to the gay, gay people! Power to the People!” Everyone rose to their feet and joined in, repeating the refrain and using other appropriate adjectives: Red, Brown, Women, Youth and Student. (Although the BPP officially supported “white power for white people” alongside all other powers to the people, the crowd in the gym didn’t go there.)

The first speech was given by Michael Tabor, a young member of the party who had written a pamphlet entitled “Capitalism Plus Dope Equals Genocide,” and was one of the 21 defendants in a New York conspiracy trial. Like Newton, Tabor had only recently been released on bail. At times brilliant and always charismatic, Tabor spoke for over two hours. He laid out how the present constitution was inadequate and had historically functioned to exclude and oppress “240,000 indentured servants, 800,000 black slaves, 300,000 Indians, and all women, to say nothing of the sexual minorities.”[26] Tabor’s keen analytical mind also took apart other illusions. At one point he listed the policies and actions of the US government and reminded us that then-president Richard Nixon, freshly having invaded Cambodia and daily bombing people in Vietnam, “made Adolph Hitler look like a peace candidate.” His eloquent oration suddenly broke off as he gestured in the air and demonstrated how the fist–symbol of the radical movement–should be replaced with the thumb and forefinger in the shape of a gun. Following Tabor, speakers included Audrea Jones, leader of the Boston Panthers, and attorney Charles Garry, legal counsel for Newton and Seale (then in prison). In some ways, the break between sessions was more soberly focused, yet simultaneously more exhilarating. In the streets surrounding McGonigle Hall, Muhammed Ali, an “ordinary” participant, shook hands, signed autographs and offered words of encouragement while other people talked with old friends or made new ones as they looked for a place to stay. All the while, hundreds discussed their coming task: to draft a new constitution for the US. Jubilation alongside criticism, but nowhere fear or resignation.

That evening, Huey Newton finally appeared. Only released from prison on August 5 (exactly one month before the RPCC), he was a complete stranger to practically everyone present. We had demonstrated for his freedom, read his essays, and followed his trial, but few of us had heard him speak. So many of us had put energy into organizing for his release from jail that his ability to attend was itself regarded as the fruit of our labor, as a victory for the movement. Even for “much of the [Black Panther] Party membership on the East Coast, this was an opportunity to hear and see the man for whose freedom they had been endlessly working. For much of the rank and file attending the plenary session it was a sort of celebration of their victory.”[27] Elated with our newfound power in the charged political atmosphere, our expectations of the eloquence of Newton’s speech were stratospheric. In the month he was out, he had been a busy man, offering the National Liberation Front of southern Vietnam troops to “assist” them in their “fight against American imperialism”[28] and authoring a strident article in the Panther paper fully supporting gay liberation.[29] He warned men that if they had a problem relating to homosexuals as equals it was a sign of their own male insecurity. In another public statement, he stressed the importance of an alliance with women’s liberation. He was the “Supreme Commander” of the Panthers, a title later changed to “Supreme Servant of the People,” and his orders to respect gays and feminists were essential to our unity. Newton’s presence electrified the overflow crowd. Even though the hall was completely full, thousands more were outside trying to get in. Only the firm action of Panther marshals and a promise that Huey would speak twice, kept the situation under control.[30] (His second venue, the Church of the Advocate, had 2500 people inside and more outside.) When Newton finally arrived in McGonigle Hall, he strode onto the stage surrounded by a phalanx of security people, and the capacity crowd quieted without being asked.

Huey was everyone’s hero, but once he took the microphone, we were stunned to discover he was not a charismatic speaker. In a high-pitched, almost whiney, voice he went on at length about U.S. history, using abstract analytic arguments:

The history of the United Sates as distinguished from the promise of the United States leads us to the conclusion that our sufferance is basic to the functioning of the government of the United States. We see this when we note the basic contradictions found in the history of this nation. The government, the social conditions and the legal documents which brought freedom from oppression, which brought human dignity and human rights to one portion of the people of this nation had entirely opposite consequences from [for] another portion of the people… [31]

By the time he was done, our disappointment in him was already palpable, and in turn, he said that we were not ready for analytical thinking. “They’re hung up on Eldridge’s slogans and revolutionary talk,” Huey told Hilliard immediately after his speech.[32] Unbeknownst to thousands of participants, Newton and Hilliard were totally alienated from what they called the “bogus Constitutional Convention.” Unable to connect even with Huey’s security people after his speech, the two top Panther leaders simply left the proceedings and partied at a stranger’s house.[33] Newton never appeared at the Church of the Advocate.

The next day, people broke down into working groups to formulate and discuss proposals for a new constitution. If only for a few hours, representatives of all major constituencies of the revolutionary popular movement huddled together to brainstorm and discuss ideas for achieving our goals of a freer society. The form of the gatherings was slightly different than in 1787. Each workshop was led by Panther members, who also coordinated security contingents that insured a trouble-free working environment. Panthers had also prevented the media from attending, fearing their presence would only make a circus of the proceedings. While many journalists complained about being barred from the plenary and workshops, the space created by the absence of media was too valuable to sacrifice to publicity. Here was the movement’s time to speak to itself. Seldom do groups communicate with such a combination of passion and reason. Person after person rose and spoke of heartfelt needs and desire, of pain and oppression. As if the roof had been taken off the ceiling, imaginations soared as we flew off to our new society. The synergistic effect compelled each of us to articulate our thoughts with eloquence and simplicity, and the “right on!” refrain that ended each person’s contribution also signaled that the time had arrived for someone else to speak. An unidentified Panther later described how the even the children had not been boisterous: “The children were to be for the three days like adults, infected with a kind of mad sobriety.” The same author promised:

“There is going to be a revolution in America. It is going to begin in earnest in our time…To have believed in a second American revolution before Philadelphia was an act of historical and existential faith: not to believe in a new world after Philadelphia is a dereliction of the human spirit.” [34]

In describing the workshops, she/he went on:

“The pre-literate black masses and some few saved post-literate students were going to, finally write the new constitution…The aristocratic students led by the women, and the street bloods, they were going to do the writing. So there were the first tentative meetings, led brilliantly by ‘armed intellectuals’ from the Panthers…In the schools and churches—the rational structures of the past—the subversive workshops of the future met to ventilate the private obsessions of the intellectual aristocrats and the mad hopes of the damned.” [35]

As the time allotted for the workshops drew to an end, each group chose spokespersons entrusted to write down what had been said and to present our ideas to the entire plenary’s second session.

As is clear in the documents, differences of viewpoint were sometimes simply left intact rather than flattened out in an attempt to impose a Party line.[36] Under more “normal” circumstances involving such a diverse collection of people in groups as large as 500 persons, screaming fights (or worse) might have been expected, yet these workshops generated documents that offer a compelling vision of a more just and free society than has ever existed. Alongside an international bill of rights and redistribution of the world’s wealth, there were calls for a ban on the manufacture and use of genocidal weapons, as well as an end to a standing army and its replacement by “a system of people’s militia, trained in guerrilla warfare, on a voluntary basis and consisting of both men and women.” Police were to consist of “a rotating volunteer non-professional body coordinated by the Police Control Board from a (weekly) list of volunteers from each community section. The Police Control Board, its policies, as well as the police leadership, shall be chosen by direct popular majority vote of the community.” The delegates called for an end to the draft; prohibition on spending more than 10% of the national budget for military and police–a provision that could be overridden by a majority vote in a national referendum–and proportional representation for minorities and women (two forms of more democracy missing from the constitution adopted in 1789). Universities’ resources were to be turned over to people’s needs all over the world, not to military and corporate needs; the billions of dollars of organized crime wealth was to be confiscated; there was to be free decentralized medical care; sharing of housework by men and women; encouragement of alternatives to the nuclear family; “the right to be gay, anytime, anyplace”; increased rights and respect for children; community control of schools; and student power, including freedom of dress, speech and assembly. Although there is one paragraph in which “man” and “he” is used, the very first report of the workshops contained a mandate always to replace the word “man” with “people” in order to “express solidarity with the self-determination of women and to do away with all remnants of male supremacy, once and for all.” As summarized by the BPP a week later:

“Taken as a whole, these reports provided the basis for one of the most progressive Constitutions in the history of humankind. All the people would control the means of production and social institutions. Black and third world people were guaranteed proportional representation in the administration of these institutions, as were women. The right of national self-determination was guaranteed to all oppressed minorities. Sexual self-determination for women and homosexuals was affirmed. A standing army is to be replaced by a people’s militia, and the Constitution is to include an international bill of rights prohibiting U.S. aggression and interference in the internal affairs of other nations…The present racist legal system would be replaced by a system of people’s courts where one would be tried by a jury of one’s peers. Jails would be replaced by community rehabilitation programs…Adequate housing, health care, and day care would be considered Constitutional Rights, not privileges. Mind expanding drugs would be legalized. These are just some of the provisions of the new Constitution.” [37]

In the society at large: racism, patriarchal chauvinism and homophobia; at the RPCC: solidarity, liberation and celebration of difference. From this vantage point, the RPCC provides a glimpse of the break from “normal” life. It prefigured the kind of international system that was thought to best replace the current one composed of militarized nation-states and profit-hungry transnational corporations. Scholar Nikhil Pal Singh has noted that the RPCC

“was an astonishing attempt to imagine alternative forms of kinship and community…Liberation politics, as inaugurated and exemplified by the Panthers, in other words, was based less upon the defense of reified notions of identity than upon the desire to fracture a singular, hegemonic space by imagining the liberation of manifold symbolic spaces within the (national territory, from the body, to the streets, a section of the city, the mind itself).” [38]

The Philadelphia constitution’s international bill of rights was one indication of just how much the legitimacy of patriotism was transcended. Structurally situated in the center of the world system, the popular movement’s imagination expounded the contours of a new world—not simply a new nation. The twin aspirations of the global movement of 1968–internationalism and self-management–were embodied throughout the documents. The phrase “self-management” may not have been used in the documents, but its American version, “community control” was used in reference to schools, police, women’s control of their own bodies, more autonomy for children, students and youth. We did not attempt to create paradise, but rather to mitigate the structures of repression (police, racism, patriarchal authoritarianism, the military) that were the source of our unfreedom. We sought at least to go halfway to paradise, fully conscious that we will never be absolutely free. If we continually jump halfway to paradise, never reaching it, we nonetheless approach it.

Thirty years later, the RPCC could be thought of as the first national gathering of the Rainbow Coalition, originated by Fred Hampton in Chicago and popularized by Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaigns. But it should not be confused with electoral politics, even though within that limited sphere, the idea of proportional representation, introduced by the Philadelphia convention, has since become part of many groups’ understanding of how to better organize the US.[39] In addition, the concept of a national referendum, part of the spontaneously generated constitution, also seems like an excellent innovation whose provision in the constitution would have meant that the war in Vietnam would certainly have come to a faster end.

Some of the demands today appear outlandish, particularly those related to drugs. After calling for “eradication” of hard drugs “by any means necessary” and help for addicts, the workshop on Self-Determination of Street People came to the conclusion that:

We recognize that psychedelic drugs (acid, mescaline, grass) are important in developing the revolutionary consciousness of the people. However, after the revolutionary consciousness has been achieved, these drugs may become a burden. No revolutionary action should be attempted while under the influence of any drug. We urge these drugs be made legal. Or rather they should not be illegal, that is, there should be no law made against them.

Significantly, the RPCC position on drugs displays graphically that more individual freedom was part of the aspirations of the Panther-led bloc, that this impetus, while appearing to some as only concerned with minorities, actually formulated universal interests. No one should discount or trivialize the importance of the drug issue. As the primary symbolic vehicle used for the imposition of class rule and cultural hegemony, it affects hundreds of thousands of people daily. One in three male prisoners in New York were serving a drug sentence in 1997; nationally, that figure is six of ten women; and in California, one in four male state prisoners (and four out of ten females) is doing time for drugs.[40] According to the FBI, there were 682,885 arrests for drugs in 1998, 88% for possession not for sale or manufacture, and since Clinton has been president, more than 3, 500,000 people have been arrested for drugs.[41] Given the existing system’s abysmal failure to wage an effective “war on drugs,” its continual enrichment of organized crime syndicates while thousand of users languish in jails, and the irrationality of alcohol’s and cigarettes’ legal status compared with the illegal status of marijuana, history’s judgment may yet prove that the RPCC policies are more sane and prudent than those now in place.[42] In two European venues apparently unaware of the RPCC, the Panther position on drugs essentially appeared unchanged: among Italian youth in the 1970s known as the Metropolitan Indians and in Christiania, a countercultural community in Copenhagen for over thirty years.[43]

Panthers went on the attack against heroin dealers, confiscating cash and flushing their stash after giving them plenty of public warnings. In one of the more daring actions undertaken by movement activists, H. Rap Brown was captured by police after he was cornered on the rooftop of an after-hours club frequently by big dealers—a hangout he and others had sought to close. Ron Brazao, underground from a 1970 bust of the Panther Defense Committee in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was killed in a shoot-out with a dealer in Marin, California in 1972. Dozens of similar accounts lead to the inescapable conclusion that the movement’s war on hard drugs was costing too many casualties.

Comparing the Platform and the Constitution

Comparing the words of two men with those of thousands of people four years later could be thought of as unfair to either side. I must admit that Newton and Seale are heroes to me and always will be. Yet I want to emphasize (and I think Bobby Seale would agree) that the capability of “ordinary” people to organize and speak for themselves, to run their own institutions and manage all of their own affairs, can be astonishing. Within the constraints of the existing system, it takes moments of exhilarating confrontation with the established powers to lift the veil concerning people’s capacities, moments of the “eros effect” in which everyday life in the hoped-for society of the future is prefigured. Unleashed from institutional masters and political bosses, spontaneous actions of millions of people can be a potent force in national and local politics. Even when they fail to accomplish their immediate objectives, they can have far-reaching international effects as well.[44]

To be fair to Seale and Newton as well as to appreciate properly their individual historical roles means to place their program and platform at the beginning of a turbulent and rapidly changing historical epoch. Between the Oakland launch of the Party and the RPCC, four years of rapid change occurred, transforming the nation and the BPP as part of it. In the months after Philadelphia, Huey had a change of heart about the direction of the party, and he enunciated a new orientation, one he called intercommunalist.[45]

When held up against the RPCC documents, the 1966 program is timid, its vision limited. The program and platform contain no mention of international solidarity. While there is an understanding of “people of color in the world who, like black people, are being victimized by the white racist government of America,” Third World people were coequal objects of repression; they had yet to become subjects of revolution. Nowhere in the platform is there a hint, for example, of Huey Newton’s subsequent offer to send troops to the National Liberation Front of southern Vietnam to assist them in expelling the US. Nor are gay people’s rights, the liberation of women, and proportional representation of minorities and women anywhere to be found in the 1966 documents. Not only is women’s liberation conspicuously absent, but the idea of Panther women fighting as soldiers alongside the National Liberation Front, an idea insisted upon by Huey, was inconceivable in 1966.

Compared with the exemption of black men from military service, the RPCC calls for an end to a standing army. Rather than black prisoners receiving new trials, ALL prisoners were to be judged afresh by decentralized revolutionary tribunals. The modest national reparations of 40 acres and two mules for African-Americans were superseded by international reparations and the redistribution of the planet’s wealth. The chart summarizes the positions adopted in the two sets of historic documents.

| Platform (Black Nationalist phase of the BPP) | September 1970 Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention (Revolutionary Internationalist phase of the popular movement) |

|

|

As should be apparent, comparison of the political program of the BPP with the vision of the popular movement at the RPCC calls attention to the ways in which the movement itself surpassed the visionary capacity of its most heroic and historically prescient leaders and organizations (all of whom, despite their centrality to the movement, remain partial and fragmentary). I want simultaneously to emphasize, however, that unlike the amorphous RPCC gathering that produced no concrete organization or ongoing program, Newton and Seale were ready to act and did act immediately after they wrote the program. Even in comparison to the previous year’s conference against repression that the Panthers had pulled together, RPCC participants were never asked to make a long-term commitment.

The BPP was steel, standing firmly up to police barbarity, and the popular movement was water, rapidly flowing with the currents of popular consciousness and actions. More than any other US organization in the latter half of the twentieth century, the BPP pushed ahead the revolutionary process, and this dialectical synchronicity of popular movement and revolutionary party, the interplay between the two, their dependence on each other and mutual amplification, accelerated and reached its climax at the RPCC. Even the purest steel will explode as water contained within it turns to steam. As the movement spontaneously surged in militant and unforeseen directions, the Panthers, unable to hold the disparate forces together, burst asunder from the pressure of the popular impetus from which it originated—and whose development it had accelerated. In many cities, Panthers and others responded to police repression by taking up arms and meeting the enemy with gun in hand. In 1970, the popular impetus from below involved millions of people, but as historical events turned into war against the police, the space for popular mobilizations and political engagement collapsed. Simultaneously the dynamic tension among the various tendencies contained within the BPP proved too much, and the organization exploded from within. Inside one vanguard party, there had been many conflicting directions: formation of armed groups or consolidation of a legal political party; autonomy for African-Americans or leadership of an emergent rainbow; a black nation plebiscite or an international bill of rights. As long as it was tied to a vibrant popular movement, the Party’s various tendencies had been able to coexist.

All movements experience rises and declines. The Philadelphia convention expressed the apex of the popular insurgency we call the sixties movement. For thousands of us who participated, it became the pivot around which mutual synergy, celebration of difference and most importantly, UNITY in the struggle turned into their opposites: mutual self-destruction, internecine warfare and standardization in the ranks. When Newton and Hilliard left the plenary after Huey’s speech, no one knew it at the time, but the high point of the movement had passed.

The stage was set for the subsequent split that tore the BPP (and the movement) apart. Although Huey would later disclaim any responsibility for the “crazy Constitutional Convention” and see it as part of Eldridge’s misdirection of the party, the Panther program Huey wrote had pointed toward the RPCC. Although Newton could not understand it, Cleaver’s implementation of the Panther program was part of his desire to follow the leadership of Newton[46]—not, as subsequently maintained—an attempt to overthrow him. In his memoirs, Hilliard tells us that Huey thought his original vision ran completely counter to “Eldridge’s plan to create a national popular front with this crazy Constitutional Convention…”[47] The division of opinion on the RPCC was used by the FBI as a means to initiate the split between Huey and Eldridge. The Los Angeles bureau wrote a memo recommending that “each division which had individuals attend [the RPCC] write numerous letters to Cleaver criticizing Newton for his lack of leadership…[in order to] create dissension that later could be more fully exploited.”[48]

The Fate of the Philadelphia Constitution

The idea behind the RPCC was that there would be a two-step process, first drafting and later ratifying the new constitution. After being warmly accepted by the 5,000 to 6,000 at Sunday’s plenary, the documents produced in Philadelphia were supposed to be circulated by a “continuance committee” that formed on Monday. Then discussions at the local level (as well as among the party cadre and leadership) were to lead to a second gathering, originally scheduled for November 4 in Washington DC. This second convention was to consider ratification and implementation of the final document. The date of the second convention was changed to Thanksgiving weekend (November 27, 1970). When thousands of people (7500 according to one estimate)[49] arrived in DC, however, they were sadly disappointed when the convention failed to materialize. Apparently the Panthers refused to pay the full rent for use of several buildings at Howard University where the plenary was to have transpired.[50] No meeting occurred on the first night, and Newton told those who attended his speech the following evening that they had a “raincheck” for another convention to be held after the revolution. He subsequently made clear that he had had a change of mind about the wisdom of continuing with the new constitution as well as with the entire idea of building the broad alliance into a hegemonic bloc capable of leading the whole society forward.

Rather than allow the insurrectionary impulse to continue, he systematically undermined and blunted the revolutionary initiative and aborted the multicultural alliance the Panthers had built as part of the Free Huey campaign. In a manner reminiscent of how Stalin had treated Trotsky, every form of political deviation from Huey’s new line was blamed on Cleaver. Huey closed down nearly all chapters of the BPP and concentrated cadre in Oakland where he could personally supervise them. He claimed ownership of the Party, copyrighted the newspaper, and even whipped Bobby Seale to assert his autocratic control.[51] Insisting it go “back to the black community,” he also confined the Party’s public actions to maintenance of Oakland’s survival programs and electoral politics. With these revisions underway, Newton secretly tried to control Oakland’s drug trade and fell into drug addiction. All that was left was for time to take its toll before the Panthers as an organized force were history.

There were many reasons why the BPP leadership changed their goals and distanced themselves from the movement’s publicly formulated aspirations at the RPCC. Under murderous attack across the country, the Party was on the defensive, its leaders scattered in jails or in exile. From these isolated positions, key leaders were far away from the rapidly transforming popular initiatives that accomplished more in weeks than history usually accomplishes in decades (throwing off the shackles of sexism and homophobia, racism and authoritarianism, forging a new popular space for action). The centralized Leninist organizational form of the Panthers also made the Party’s leadership more vulnerable to disruption by the police, not less. Locking up, murdering and sending into exile a dozen or so individuals incapacitated the central committee and the Party. When the BPP’s centralized structure fell into the hands of David Hilliard, the only member of the top leadership left in Oakland, authoritarian tendencies multiplied. Even though the popular movement and most cadres initially supported him, many in the Party bitterly resented his heavy-handed imposition of order. Along with his brother June, he forced implementation of directives that were never discussed, and the primacy of Oakland enervated emergent leadership around the country. When Huey came out of jail, the Supreme Commander intensified central control and became the chief enforcer of party discipline.

The RPCC’s amorphous fluidity contradicted the rigid structure of Panthers. Its constituencies were so diverse and scattered, however, that while the Panthers were able to unite and inspire us, and their organizational form was insufficient to hold us together—even if they had been able to formulate a collective will to do so. Soon after the DC fiasco, the Panthers bloodily split apart along much the same lines as SDS and most other movements in the world in the same period (strident insurrectionism vs. a more sedate community-based orientation). As the movement split, the system simultaneously destroyed the most radical advocates of revolution (George Jackson, the Attica inmates, the Black Liberation Army, etc.) while reforming itself in order to prevent in advance the conditions for further popular mobilization. While individuals from the broad array of constituencies at the RPCC continued to work with the Panthers, the popular movement never regained its amazing unity and synergy.

As the movement disintegrated, the Philadelphia constitution was apparently tossed on the dustbin of history—or was it? United in Philadelphia, the popular movement’s vision continues to animate action. In the three decades since the RPCC, millions of people have acted to implement various portions of the Philadelphia constitution. In the 1970s, the feminist movement initiated a campaign for one of its provisions—equal rights for women and men. In the 1980s, the disarmament movement sought another: a ban on the manufacture and use of genocidal weapons. But the most impressive actions in response to Philadelphia were undertaken by the prisoners’ movement that swept the United States in the months after the Philadelphia convention. From California to New York, imprisoned Americans like no other constituency were activated by the movement’s call for justice. As inmates demanded decent, humane treatment, a wave of rebellions swept through the nation’s prisons, culminating in the uprising at Attica State Prison in New York in which 43 people were killed almost exactly one year after the RPCC. Many of the RPCC’s ideas have already stimulated subsequent social movements, and they will probably do so again in the future. If just two RPCC provisions were enacted—proportional representation and a provision for national referenda—the current political structure would be far more representative of the entire population. As the “rationality” of the existing world system as a whole becomes increasingly unreasonable, the reasonability of the decentralized, self-managed forms of governance advocated by the RPCC will receive renewed attention.

If not for the split in the party and the disintegration of the movement, who can gauge in what direction this hegemonic bloc might have led? Who can be certain where the sixties upsurge might have ended? Like a baby learning to speak, the revolutionary movement of 1970 was immature—unprepared to provide long-term responsible leadership capable of leading the whole society forward. Unable to reach the second stage of struggle—consolidation of the revolutionary impetus—it split into thousands of pieces.

Three decades later, the RPCC remains unexplored, a unique event that sparkles with insight from the hearts and minds of thousands of participants who represented millions more in 1970. At the beginning of the 21st century, the phenomenal pace of change accelerates, and shifting group identities, changing affiliations, atomization and detachment characterize the daily life of many nations. Since these postmodern elements make it problematic to focus on groups that provide universalistic vision, we might be led to the conclusion that the RPCC represented the last of the great public gatherings of modernity—instead of a precursor to our multicultural future. It was both—and in so being became the hinge around which this entire historical period moved.

George Katsiaficas is author or editor of eleven books, including several on the global uprising of 1968 and European and Asian social movements. Together with Kathleen Cleaver, he co-edited Liberation, Imagination, and the Black Panther Party. A longtime activist for peace and justice, he is international coordinator of the May 18 Institute at Chonnam National University in Gwangju, South Korea, and is based at Wentworth Institute of Technology in Boston.

He is credited with developing the theory of the “eros effect”—the transcendental qualities of social movements to not only imagine a new way of life and a different social reality, but to instantiate it.

A Fulbright Fellow, student of Herbert Marcuse, and long-time activist, he is the author of The Imagination of the New Left: A Global Analysis of 1968. His book, The Subversion of Politics: European Autonomous Social Movements and the Decolonization of Everyday Life, was co-winner of the 1998 Michael Harrington book award.

Eros Effect – George Katsiaficas www.eroseffect.com

Further Reading: RPCC-WORKSHOP-REPORTS

1 I wish to acknowledge the helpful comments on earlier versions of this article given to me by Kathleen Cleaver, Russell Shoats, Stew Albert, David Gullette, Billy Nessen and Victor Wallis.

2 In Bitter Grain, the Story of the Black Panther Party (Los Angeles: Holloway House Publishing Co., 1980), author Michael Newton maintains that the event analyzed in this essay never took place. See p. 157.

3 I develop this concept in relation to the autonomous movement (or Autonomen) in Europe to indicate that seemingly spontaneous crowd behavior can have a great underlying intelligence. See The Subversion of Politics: European Social Movements and the Decolonization of Everyday Life (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1997).

4 For more discussion, see the introduction to this volume.

5 Checking a dozen of the most important histories of the sixties in the US, ten did not even mention the RPCC and the other two contained only brief references to it. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first attempt to deal with it even in an essay. Charles Jones, one of the pre-eminent historians of the BPP, points out that leaders’ autobiographies and analyses of events are more common in Panther historiography than are rank-and-file accounts or longitudinal studies. The paucity of material about the RPCC indicates the extent to which it is a forgotten case even among movement events. See Jones, “Reconsidering Panther History: The Untold Story” in Charles E. Jones, editor, The Black Panther Party Reconsidered (Baltimore, Md: Black Classic Press, 1998) pp. 9-10.

6 See Joseph A. Califano, Jr., The Student Revolution: A Global Confrontation (New York: W.W. Norton, 1970) p. 64.

7 New York Times, January 2, 1971.

8 The Imagination of the New Left: A Global Analysis of 1968 (Boston: South End Press, 1987, new printing 1998).

9 This process is described in Bobby Seale, Seize the Time! (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 1991) originally published in 1970.

10 Seale, op. cit., p. 62.

11 See The Black Panther, August 15, 1970, p. 19 for one example.

12 See particularly Tracye Matthews, “‘No One Ever Asks, What a Man’s Place in the Revolution in the Revolution Is’: Gender and the Politics of the Black Panther Party 1966-1971,” in Charles Jones, op. cit. pp. 267-304. The entire section on gender dynamics in Jones’s book is excellent. “Also see Kathleen Cleaver’s chapter in Liberation, Imagination and the Black Panther Party (Routledge, 2001). An earlier version of this essay on the RPCC also appeared in that volume.”

13 Hilliard, op. cit., p. 312.

14 Russell Shoats, unpublished memoir.

15 Manning Marable, Race, Reform and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America (Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 1971) p. 110.

16 Hilliard, op. cit. p. 313.

17 The Black Panther, 9/19/70; 10/31/70, p. 7.

18 Off the Pigs! The History and Literature of the Black Panther Party, G. Louis Heath, editor, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1976) pp. 186-7.

19 “Newton, At Panther Parley, Urges Socialist System,” The New York Times, September 6, 1970, p. 40; Paul Delaney, “Panthers Weigh New Constitution,” New York Times, September 7, 1970, p. 13.

20 Washington Post, November 27, 1970, p. C10.

21 New York Times, September 6, 1970, p. 40.

22 Kit Kim Holder, The History of the Black Panther Party, 1966-1972, doctoral dissertation (University of Massachusetts, 1990) p. 131.

23 I call this phenomenon the “eros effect.” See my book, The Imagination of the New Left: A Global Analysis of 1968 (Boston: South End Press, 1987). Also see my exchange with Staughton Lynd in Journal of American History, June 1990, pp. 375-377. Lynd originally asserted that “…as a resident of the Kent-Lordstown area for more the ten years, I have yet to meet a participant in either happening who felt that the events at Kent caused those at Lordstown.” After reading the exchange, Tom Grace, one of the students involved at Kent State, sent me a leaflet from Lordstown that he had saved for twenty years that proved impetus for the actions there was, in fact, derived at least in part by the shootings at Kent State.

24 Russell Shoats, unpublished memoir, p. C. That the armed struggle was endorsed by the BPP—including Huey Newton—can be ascertained by their reaction to Jonathan Jackson’s taking over a courtroom in Marin, California on August 7, 1970, an action that cost many lives. The relation and articulation of these levels of struggle remains an unresolved problematic facing radical movements. For discussion, see p. 182 in The Imagination of the New Left.

25 The Black Panther, 8/22/70; 8/29/70, p. 11.

26 The Black Panther, 9/19/70, p. 11.

27 “Not to Believe in a New World after Philadelphia is a Dereliction of the Human Spirit,” unsigned article, The Black Panther, 9/26/70, p. 17.

28 Holder, op. cit., p. 131.

29 See his “Letter to the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (with Reply)” in George Katsiaficas (ed.), Vietnam Documents: American and Vietnamese Views of the War (Armonk, N.Y.: Sharpe, 1992) pp. 133-6.

30 The Black Panther, 8/21/70, p. 5.

31 Holder, op. cit., p. 132.

32 “Huey’s Message to the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention Plenary Session September 5, 1970 Philadelphia, PA.” Document in my collection.

33 Hilliard, op. cit. p. 313.

34 Hilliard, op. cit. p. 314.

35 “Not to Believe in a New World after Philadelphia is a Dereliction of the Human Spirit,” unsigned article, The Black Panther, 9/26/70, p. 19.

36 Ibid. p. 20.

37 See point 2 of the workshop on the Family and the Rights of Children for one example.

38 “The People and the People Alone were the Motive Power in the Making of the History of the People’s Revolutionary Constitutional Convention Plenary Session!” The Black Panther, Vol. V No. 11, September 12, 1970. p. 3.

39 Nikhil Pal Singh, “The Black Panthers and the ‘Undeveloped Country’ of the Left,” in Charles Jones, op. cit., p. 87.

40 See Douglas Amy, Real Choices/New Voices: The Case for Proportional Representation Elections in the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993).

41 Laurie Asseo, “Study Ties Drug War, Rise in Jailed Women,” Boston Globe, November 18, 1999, p. A18.

42 Chris Bangert, “Marijuana: the hemp of the past and the ‘drug’ of the present,” unpublished paper, Brewster, MA, 1999.

43 Enforced at a cost of billions of dollars per year and tens of thousands of perpetrators of victimless crimes in jail, the present drug policy includes decades of evidence of the CIA’s involvement with both the heroin trade in Southeast Asia and the cocaine trade in Central America —as well as existence of a Contra-connected crack pipeline to Watts (South Central Los Angeles) first reported in the pages of the San Jose Mercury-News. As a result of the continual generation of mega-profits based on certain drugs’ illegal status (witness the price of oregano or baking soda in any supermarket), control of the drug trade by the “government within the government” is a major source of funds for covert operations hidden from public and Congressional oversight. To understand these dynamics, one could begin with Leslie Cockburn, Out of Control: The Story of the Reagan Administration’s Secret War in Nicaragua, the Illegal Arms Pipeline, and the Contra Drug Connection (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1987). Also see Alfred McCoy, The Politics of Heroin: CIA Complicity in the Global Drug Trade (New York: Lawrence Hill, 1991).

44 For more information on these groups, see my book, The Subversion of Politics: European Autonomous Social Movements and the Decolonization of Everyday Life.

45 Indeed, if the press continued to report spontaneously generated popular acts of rebellion as they did in the 1960s—and there is considerable evidence the media do not—a strong argument could be made that with the advent of television and satellites, the international impact of uprisings, general strikes, insurrections, massive occupations of public space–all the weapons in the arsenals of popular movements—would be their most notable effect.

46 Floyd W. Hayes III and Francis A. Kiene III, “‘All Power to the People’: The Political Thought of Huey P. Newton and the Black Panther Party,” in Charles Jones, op. cit., pp. 157-173.

47 See The Black Panther, June 13, 1970, p. 14. Cleaver insists the RPCC was “actually implementation of Point 10 of the Black Panther Party platform and program.”

48 Hilliard, op. cit., p. 308.

49 Hilliard, op. cit., p. 317.

50 Ivan C. Brandon, “Panthers Seek Site for Talks: Negotiations with Howard Broken Off,” Washington Post, November 27, 1970, p. C1.

51 Ibid.

52 Elaine Brown, A Taste of Power

©2026 Black Earth Institute. All rights reserved. | ISSN# 2327-784X | Site Admin