a literary journal published by the Black Earth Institute dedicated to re-forging the links between art and spirit, earth and society

Ross Martin

Permanerds

Can Mound Builders Help Save the Environment?

My best friend and fellow plant nerd, Marga, stood twirling a willow whip in her hand. “Andrew Faust is teaching a Permaculture workshop at the Open Center this summer. Want to take it, Rossi?”

“Are you kidding? After the last experience?” I didn’t need to remind her about the workshop we’d walked out of, where the discussion devolved into a debate of the nutritional value of composting human manure and menstrual blood.

For the last couple of decades Marga and I had joined forces to restore, manage, and defend La Plaza Cultural Armando Perez, a community garden and park servicing Manhattan’s densely and diversely populated Lower East Side (LES) for almost forty years. It was a membership based nonprofit organization; the land owned by the city but stewarded solely by members and other volunteers. Marga and I were so close my partner, Eric, joked that she was my gardenwife.

Later that evening I Googled Andrew. He ran The Center for Bioregional Living. Its site listed him as one of the “premier Permaculture teachers and designers in North America.” He’d lived off the grid in West Virginia for eight years where he built a homestead and straw-bale house, then moved to Brooklyn in 2007, to apply his knowledge to urban landscapes.

Intriguing, but I wasn’t convinced about the usefulness of the discipline to the environment we gardened. I visited the Open Center website. It called itself “New York’s leading center of holistic learning and world culture.”

“Yuck. Just what we need, more tree-hugging, crystal-rubbing, long-hair-wearing hippy freaks,” I later told Marga, inwardly wondering why I resisted. Permaculture appealed to me; however, I’d yet to see any realistic applications of the principals.

“Humor me and look up the Design Certificate,” she responded.

Faust described the discipline as “an ecological design science that provides insights and practical techniques for living a fruitful and abundant life.” I liked that. And “a worldwide movement that is helping to regenerate local ecologies and economies, a solution oriented approach to retrofitting our societies.” That too.

He promised to teach individuals to use the “tools of Permaculture in urban environments with lectures, extensive written information, field trips and hands-on activities in,” among other areas, “urban redesign, passive solar and natural building, inner-city gardening techniques, indoor gardening and mushroom cultivation, living machines, natural waste water treatment, rain and rooftop gardens, cleansing polluted air with plants,” along with a number of science-like words I didn’t understand. Right up my alley.

“Okay, I’ll do it,” I told Marga over coffee, “but only under two conditions. First, you do the project with me. A redesign of La Plaza. I want to make the garden more self-sufficient and sustainable.”

“Fair enough. The other?”

“Any mention of ‘humanure,’ and I’m demanding a refund.”

“Deal,” she laughed. We clanked mugs.

*****

Early Saturday morning, we walked into the Sixth Street Community Center’s cavernous back room. Sunlight streamed through the south facing windows. Participants hauled chairs from under the front staircase to the perimeter and aligned them in a semi-circle. Andrew stood at the apex, wearing a short-sleeved button-up plaid shirt and frayed blue jeans, his long straight brown hair pulled in a tail. The air was still, hot, and humid. An open door led to a fenced-in secret garden. I’d lived just blocks away for nearly twenty years, been to countless meetings here to organize our battle to save community gardens, and I didn’t even know it existed. How could that lovely green space escape my notice?

Behind Andrew was a table arrayed with books. He eyed the crowd–the usual suspects, all but two white and only five men; at least their ages ranged. Rambling a lot and bragging a little, he introduced the workshop agenda. Permaculture, he told us meant “permanent agriculture, an antidote to the unsustainable military industrial complex mind frame presently governing the world.”

Bored, I turned to Marga and rolled my eyes. I’m not a fan of conflated words, nor do I like a discipline that capitalizes its title as if it were a religion. Nonetheless, the melodic timber of Andrew’s voice entranced me. I jotted down every word I could, frantically trying to record it all. Perspiration beaded my brow and a familiar tingle excited my temples.

He started with a not so brief history of the universe, telling us how miniscule bits of distant stars coursed our veins. He traced the story of humans from life in trees to the advent of agriculture in Mesopotamia, going on to describe how this relatively recent development changed the world, irrevocably leading to industrialization, globalization, and the present information era. This took him hours, all without the aid of notes or visuals. Mesmerized, by the time he broke for lunch, I had filled over half of my notebook. Sweat dripped from my armpits.

The second half was no less interesting but much more depressing. Andrew detailed pretty much every human-induced environmental problem plaguing our species since the dawn of the agricultural-industrial-military complex. After the World Wars, chemical companies used their materials and resources, subsidized by the government armed forces, to develop pesticides, fertilizers, and energy. It took ten calories of fossil fuel to put one calorie of food on our tables. At that rate the food economy was doomed to collapse in our lifetimes. He talked about the nuclear problems, hydroelectric problems, coal problems, and of course, oil problems. “And, folks, driving hybrids, eating organic foods, and harvesting the wind and sun are not going to get us out of this mess,” he warned. “The energy and waste involved in the batteries to harness the electricity alone counteract positives gained. The answer isn’t technology. It is the way we live. We. Must. Consume. Less.”

He put his hand down to emphasize each word, paused to let the message sink in, and went on. “So I’ve told you how we got here and what that means. Next week I will give you ‘Perma-Lenses’ to reveal how to heal the system.”

I’d heard the message of doom and gloom before but never this extensively, and never with a promise of a positive practical way out. In the eight years since La Plaza had been named a park, we’d muddled along trying to figure out who we were as an organization and where we were going. We’d inherited both a vision and a mess. In the late 70s, Latino ex-gang members calling themselves CHARAS had stepped into the gaping lots left by collapsed or burned tenement buildings and set out to create green spaces as a part of larger guerilla urban renewal efforts. Futurist Buckminster Fuller donated geodesic domes for a community center on the site; and artist Gordon Matta-Clark started the Loisaida Environmental Resource Center, teaching youth architecture and construction using materials recovered through his work deconstructing the tenements. But then Matta-Clark died. The city threatened to develop. And CHARAS moved into a mammoth schoolhouse on the block, theirs if they didn’t fight development. CHARAS didn’t. In fact, the entire Latino community walked away from La Plaza. Others in the community fought, however, and won—at least temporarily. Years later, when I got involved, the city once again sought to build. A ten-year struggle, and we were named a park, just as the city sold CHARAS’s building out from under them to a developer wanting to house a private dormitory.

So we had our park—renamed after Armando Perez, a slain local leader and director of CHARAS. We had a storied past. And now, listening to Faust’s message, I believed we had a future. Eureka moment: I decided there and then, Andrew was my evangelist and Permaculture my religion.

Early on philosophers and theorists noticed the importance of the Internet and globalization. They postulated that we would work from home on computers and therefore commute less, in theory not using as much energy. That’s happened, the staying at home part anyway. However, we’ve not only increased our at-home use of energy and the production of electronic gadgets and inherent waste, but now everything worldwide is brought to our doorsteps with the click of a mouse and touch of a button, often from the most far-flung parts of the planet. We spend much of our time indoors, staring at a screen not socializing with people in person, and we’re so far from natural experiences and our neighbors that scientists have noticed anxiety associated with our removal. It has a name: nature deficit disorder. As I pondered it all, I decided our design should revolve around creating space for all people to come experience nature and learn about their role within it.

“Some of you might be wondering whether this is possible in an intense urban environment,” Andrew said at our next session. “Not only is it, just by living here most of us leave a smaller carbon footprint than the rest of the country. We walk, bike, and use public transport more than drive. Living in smaller spaces we consume less all around. Shopping in farmers markets we eat locally grown, seasonal foods. But there are many more ways city dwellers can live sustainable lives.”

I’d considered all this before and sometimes tried to convince myself that self-induced deprivation—living in tenement squalor—was a grand green experiment. I was noble, not pathetic. I was an eco-martyr for the greater good of planet earth and therefore not a loser. All this was moot every time I took a cab, drove hundreds of miles to get plants, bought blueberries from Chile in January at Whole Foods, or boarded a jet bound for some exotic escape. At least I didn’t drive an SUV an hour to and from work daily, I’d tell myself as I ordered a glass of wine from the flight attendant.

Andrew told us about the ways urbanites could live more ecologically, about growing food in containers on rooftops, sidewalks, and windowsills. Buildings should be designed or retrofitted to harvest rainwater for food production, to conserve, even generate, their own electricity, reclaim wastewater—sewage used as fuel. Again I stuffed my notebook with particular emphasis on actual things we could put into practice at La Plaza.

He described stacked functions—built in redundancy—for our projects. “The output of one solution can be the input of another,” he said.

“I like the chicken tractors,” Marga told me over lunch. This elegant idea was a movable coop with no floor. The fowl, placed in fields, ate weeds while pooping and pecking, fertilizing and aerating the soil. When the site was cleansed and fed, they could be moved to a new patch.

“Not real practical for La Plaza. We don’t have fields. We could get chickens though. I also want to reintroduce bees and have an apiary.”

“Let’s grow mushrooms and sell them.”

After our break Andrew introduced us to the edible forest garden concept. He said that the North Eastern deciduous woodland had been entirely clear-cut since colonial settlement. Lumber built and fueled the young nation. Forests were resilient and had grown back due to the depth of rich ancient soils blanketing the region coupled with ample moisture. “The land wants to be forested,” he said. A garden consisting of fruit and nut trees, berry shrubs, and perennial food groundcover crops was a sustainable solution for landscapes in this environment.

That was what La Plaza could be. Our project inspired us to develop a plan to enhance and manage our edible forest garden.

Next we took a fieldtrip to Prospect Park in Brooklyn to identify trees and discuss the complexity and structure of native forests. We tramped up a brambly hill, looking for a hawthorn shrub where we startled a guy felicitating his buddy.

“Our first wildlife sighting,” I enthused, adopting my PBS voice. “Observe the mating ritual of the urban gay male in his natural habitat.”

Ignoring me, Andrew took hold of a twig and said, “Hawthorn is my favorite native shrub. It’s sturdy, hardy, drought tolerant, and prunes readily. You can use it to graft fruit bearing trees to and make an espaliered fence.” Stacked function.

He then sat cross-legged on the forest floor, pulled out a sandwich, and started eating, continuing his lecture between bites.

“Mature woods like this have a vast microbial network in the soil. Energy and nutrients are exchanged through stringy mushrooms and other fungi underfoot. It’s a vast subterranean Internet. Trees even communicate with one another, warning their relatives and friends when an infestation or disease threatens them, causing the others to produce more hormones to boost their immunity. Studies have shown that small specimens in the shade of mature canopies might even receive sugars from the photosynthesis of larger ones with more sun exposure.”

I texted Marga next to me: “dude gab’d 4 hs strait! No lunch? WTF???” We were not warned to bring one. Though he was feeding our minds, there would be nothing for our stomachs.

He’d mused about unsung fungal heroes and their ubiquitous invisible network cleansing our messes, creating soils, and supporting the web of life. This realm could become the most important ally in repairing our biosphere. Mushroom species might replace chemical insecticides, break down toxic wastes, and inhibit the spread of virulent diseases. His endless talk on subsurface toadstools made me hungrier.

The next day we toured LES gardens, observing rainwater capture systems, compost heated green houses, and remediated brown sites in many of the gardens I’d been to but never knew housed such things. I saw my neighborhood anew. Perma-lenses!

Energized and determined, we returned to La Plaza.

We sat on the stone amphitheater and Marga began. “We evolved in forests, spent thousands of years living in canopies, safe higher up, a whole different universe, predator wise. Trees move water, change weather, create environments, make rain, remove dust, pull moisture from the air, and reduce pollution. I think we need to find a way to honor them.”

“I’d also like to work with the concept of a thousand years to make just one inch of soil in the Northeast and stream water turbidity.” A common one-inch rain event, Andrew told us, overwhelmed the combined sewer systems and raw human waste was discharged into the Hudson and East Rivers. Furthermore, sediment runoff was the main source of water pollution, greatly decreasing habitat value of streams.

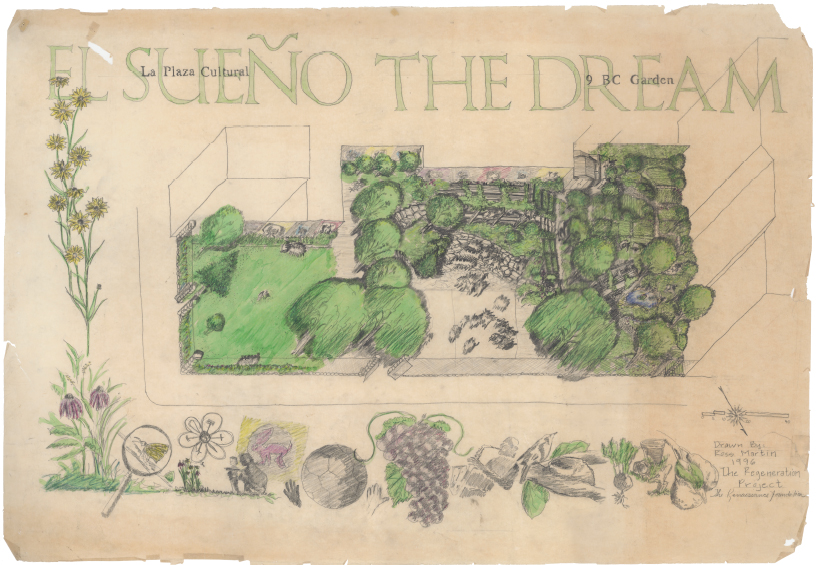

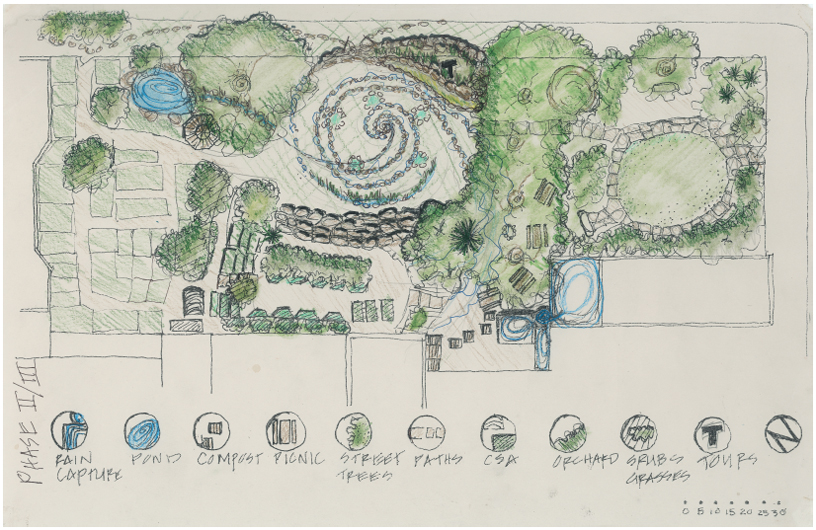

We thought about how to expand our compost system, accelerate soil creation, and reduce food and garden waste, build and manage our edible forest garden, and capture and treat storm water. We fantasized the place as the heart of a LES garden district with a resource center inspired by CHARAS, Matta-Clark, and Fuller. We produced drawings visualizing the attributes driving our ideas: how the space was used and to what extent; what portions were sunny or shady; what functioned as habitat; where it drained; where the saturated soils, deep bedrock, underground streams were located. We also postulated which micro industries could generate funds and schemed on how to incorporate the concept of the mycelium subterranean Internet. “Our own underground fungal Google—Foogle,” Marga joked.

We devised a phased design program. The first stage involved moving the greenhouse; getting a new shed; expanding and improving our compost system; building a maintenance yard and rainwater capture system; and creating an environmental education center under the Lindens. The second was re-grading the space to capture runoff in a wetland retention basin to treat storm water in a series of catchments and a biological filter system, overflow directed to a buried cistern. Last, we envisioned a kiosk to house the library and act as the garden center, functioning as a hub for local digital garden tours downloaded from the Internet.

I created a series of hand drawings. Marga prepared a presentation. When our turn came we passed around the diagrams.

“Did you draw these?” one woman asked. “They’re magnificent.”

Pride and gratitude washed over me. It was great to have our work done and the information visualized, organized, and archived. But to be complimented publicly for my illustrations made me as giddy as a little boy running free in the garden.

Now all we had to do was get approval from the board and find funding to start.

Hurricanes would have a lot to say about all that.

*****

Over the next few years we accomplished much of our dream. But it would take tragedy to help us realize our most significant work.

Two sixty-foot trees fell to Hurricane Irene’s winds, a weeping willow and European linden. A microburst blew down Ninth Street laying waste to our garden. Just over a year later Super Storm Sandy came in, surging four feet of salty water, taking in its ebb another linden and several understory trees, shrubs, and perennials, completing her smaller sister’s clear-cut. As devastating as these weather events were to our neighborhood emotionally, they provided us an opening and spurred a renewal. The tempests gave us the opportunity to work with nature’s forces.

We held a constant dialogue about what this place was, and if left alone would become, and what we—as its stewards—wanted it to be. When the great trees toppled, a hole ripped through the fabric of our community. Together we scrambled to cope, mend, and move forward. Many argued for another grand willow. Beautiful as they were—thriving to tremendous heights on our subterranean streams—we’d had a tumultuous relationship with these behemoths. As if to confirm this, one of the two remaining dropped half its crown on the sidewalk a week after Sandy’s departure.

The gap let light in. Sunshine would allow us to grow food where we never had before. Could our urban woodland provide more for us? In the spirit of self-reliance, we decided to enhance the edible forest garden. Funded through several generous recovery grants we expanded the fruit and nut orchard—an apt metaphor for our group, Eric joked—and remediated the soils. Apples, cherries, almonds, pears, and plums accompanied native serviceberries, blueberries, hazelnuts, and persimmons, and all under-planted with various perennials in the fresh new earth.

Marga and I attended a few more workshops with Andrew. At one an ecologist told us about hugel kultur—hill culture, an ancient German technique. Marga had mentioned these mounding gardens beds before, but I’d dismissed them as folly. I asked the ecologist to explain the system to me. He bent over, picked up a rotting log, took off a mushy hunk in his large hand, and squeezed it. “See that?” he asked as the water dribbled down his sleeve. “Wood rots and acts like a sponge holding water. Plants send their roots into the soft, moist tissue. Notice the stringy white mycelium. Fungus breaks down fiber and slowly releases nutrient fertilizer. Alternate layers of wood, biomass, and soil and plant directly into the mound.” Fascinating! In a matter of minutes I learned more practical information than during the entire course of the day.

There was something kind of spiritual about hugel kultur summing our efforts perfectly. We plotted building mounds out of the abundance of wood and biomass already on site, topping them with an espaliered fruit fence. I told Marga about a compost “chimney” I envisioned. I had been using a Vita Mix blender, a countertop industrial machine that sounded like “a jet engine grinding Canadian Geese”—Eric’s words—to process our kitchen scraps into liquid. It could be poured directly into chimneys in the hillside to disperse through the channels left by the rotted branches.

“They could be mounded along the perimeter to prevent future flooding!” Marga chirped.

In addition to the forest garden, we received funds to develop a nature trail. We’d created plant containers out of grape vines hand-woven around abandoned tomato cages. We sold these with seasonal plantings to my wealthy clients. Proceeds benefitted La Plaza. They kept the planters or donated them back to the garden to be dug directly into the ground. These mini hugel kulturs would be incorporated as trail markers with signs.

The idea of weaving and the metaphor of mending dovetailed nicely with the creative destructiveness of Matta-Clark’s art. We had also come across Objects to be Destroyed, a recent book about his work by, Pamela M. Lee. A grainy black and white photo of La Plaza had a caption reading, “Gordon Matta-Clark, site for Resource Center and Environmental Youth Program for Loisaida, 1977, Lower East Side, Manhattan…. This utopia of a place never came to fruition….”

But it had. And still exists, with us. What’s more, Matta-Clark, in an interview I had read, claimed the center was his best art to that date because all his other works were necessarily destroyed, only existing in pieces and pictures. We embodied his work.

Though we remain a largely white organization and our neighborhood continues to become paler and wealthier, there are a few institutions we’ve sought to engage with to encourage more diversity, purposefully and inadvertently, reaching out to local politicians and largely minority groups to help us rebuild. Paul, a strapping young Puerto Rican single father, showed up unexpectedly with his three youngsters in tow, offering to help dig holes and plant. As we tore up the tarmac, chopped down dead trees, layered the wood, biomass, and soil on our new mound, I explained our work. Because the mound ran along the well-traveled Ninth Street sidewalk many neighbors—some I hadn’t had a conversation with in years, others I’d never seen—stopped to ask what we were doing. Intrigued, Paul told me he wanted to build hugel beds in the vast campus of projects where he lived, a block away.

“There are hundreds of dead trees and we need flood control, too. I bet we could get it funded.” I dreamed of mounds snaking the LES.

We discussed the former daycare center next to my building that had been converted to house kids who had aged out of foster care and the 500-bed dorm going into CHARAS. Both threatened to alter the character of the blocks irrevocably. “Our neighborhood is changing rapidly, and I feel like if we don’t co-opt these changes, we are going to lose control,” he told me. Ironically, people like Paul, Marga, Eric, and I, along with countless other friends and neighbors, all who had helped to improve the neighborhood making development feasible, were now in jeopardy of being priced out. Essentially, we were trapped in our rent stabilized or subsidized apartments.

“Maybe we could start a mentor program between the students and the orphans to help build more mounds.”

“Yeah and we should also capitalize on the rich whities flooding our shores,” Eric remarked.

We got chickens! Four hens. Interestingly, they were very popular with Latino and African Americans passing by the park, drawing them back in. I saw this as a small improvement in what was historically a somewhat strained relationship.

When Marga and I talked one afternoon about the unlikeliness of all these rural goings-on, she said, “When I told my father I was moving here, he gasped, ‘Are you kidding? Our ancestors slaved to get out and you go and put yourself right back in?’”

“My dad spent his entire career working so we boys wouldn’t have to farm,” I replied as two chickens waddled by.

Just days before this writing, months after we completed the mound, we learned City Council Member, Rosie Mendez*, had secured a temporary reprieve for CHARAS. We attended a rally in the shadow of the hulking building in support, the sputtering torch of democracy, threatened by the one percent, still barely burning. Empowered by our verdant success and agricultural bounty, standing next to Eric and Marga, I looked at my comrades and fellow activists, a broad cast of characters, and thought, we may be the last generation able to come to this city with little but a dream, work with locals battling poverty and discrimination, and build a life while helping the community. What would our legacy be? Hugel mounds and chickens nourishing the neighborhood.

*An earlier version of the article reported that Margarita Lopez is the current councilwomen, not Rosie Mendez; the author regrets the error.

Ross Martin is a landscape architect by training but in practice designs, builds, and maintains high-end residential gardens in Manhattan. Holding a BLA from University of Arizona, and MLA from University of Minnesota, with a minor in applied ecology, he authored a thesis Suburban Residents’ Perception of Wildlife Habitat in Their Yards. For over seventeen years, Martin has also been landscape curator for Plaza Cultural Armando Perez community garden and park on the Lower East Side. He writes about restoring the venerable space and struggling with development. It deals with multitudes of characters, the cultural and environmental history of the place and surrounding environment, and the 60 plus other gardens in the neighborhood. The story spans nine years and the themes center on environmental, racial, social, and political issues, unique to urban areas. He recently published Willow Weep For Me in About Place Journal’s Tree issue.

©2026 Black Earth Institute. All rights reserved. | ISSN# 2327-784X | Site Admin