Twelve years ago, on the train ride home from a quilt show at the Park Avenue Armory, I asked myself “Did I see what I think I saw?” In a field that is riddled with the voice of the “other” and dominated by missions of “discovery”; where definition and value are assigned by the “Academy,” where can a woman who is the practitioner of the craft of quilting find voice and meaning? One can make peace with one’s ancestors — both familial and collective — by telling their stories, calling their names, and acknowledging their struggles and achievements. This is my acknowledgement of a quilting ancestor unknown to me until the moment I saw her symbols in a quilt.

Red and White Quilts, Infinite Variety was a loving husband’s (Daniel Rose) birthday gift to his wife Joanna Semel Rose. Joanna acquired eight hundred red and white quilts at yard sales, flea markets and churches in communities throughout the South, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and places too numerous to list in this limited space. There were 653 quilts from her collection on view for this one-time exhibition. I delighted in quilt designs I had never seen before in person. On display were a wide variety of church and house quilts, birds in the air, triple Irish chain designs, applique and embroidered quilts. Many of these quilts were intended for everyday use, and they were products of women’s quilting circles or family heirlooms. When I saw Infinite Variety, with quilts hanging from the Armory ceiling in several tiers throughout the room – I thought this is quilt heaven.

On my first rounds of the Park Avenue Armory, I had paid modest, almost scant attention to a large quilt titled “American Appliqué Sampler.” I was intrigued with the quilt maker(s) who had taken the time to outline the nail beds on a hand and add strings to a harp, all details giving the block a three-dimensional, modern quality. The handiwork in this quilt was fine. Who made it? I kept looking for a name amongst the blocks. Who were the women who gathered to bring their favorite symbols together into such a perfect unity? Or was this the work of a slave or servant woman who lived with a doctor or professor of some kind and had access to an in-house library?

Acts of reclamation and re-memory are occurring in the works of contemporary art quilter Patricia Montgomery, and indigenous art quilter Susan Hudson, to name a few. Montgomery has transformed the simple swing coat into an historical document/textile called “Women in the Civil Rights Movement,” which highlights the achievements of women in the freedom struggle. Women such as Diane Nash, Septima Poinsette-Clark, Dorothy Cotton, and Fannie Lou Hammer are among the twenty-plus women featured in this ambitious project. Navajo quilter Susan Hudson delves into the history of Indian children in her quilt: “Missing and Murdered Boarding School Children’s Journey to the Milky Way.” Hudson’s work is a tribute to her ancestors, their history, and their resilience despite harsh treatment. Through her art, Hudson tells stories often silenced in American culture.

It is true that my generation and those to follow are the ones who have accelerated the connection to Africa. Many American Blacks have reclaimed aspects of African music, dances, names, religions, and folkways. Pictures, herbs, and pieces of cloth are objects of “knowing.” A song remembered or a visit to a gravesite could trigger an epiphany about a hidden past.

Who knows how long the “American Sampler” quilt sat in some basement or piled up in an attic waiting for someone to find it? What does it mean to be in an impossible situation, yet have the courage to leave one’s mark? To be enslaved, bereft of kin and country, yet embodied with a fine mind, agile spirit and gifted in the tactile arts of dressmaking and quilting. To know this place, this time (estimated late nineteenth century), is all that you have. To bear the impossible yet still be able to create something new out of your past. As I walked throughout the show, I kept asking myself were any of the quilts created by Black women? I viewed two quilts with the double headed axe that is associated with the Yoruba god Shango appliqued across them. Had this quilt been created by a Black woman? With no evidence of the true provenance of the quilt, who knows for sure.

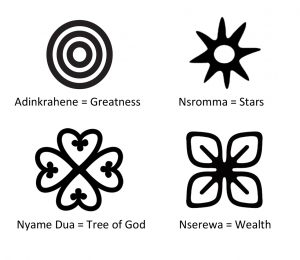

I decided to photograph the American Sampler quilt for later study. True to form, my camera battery died, but a friend consented to let me use her camera. I was fascinated by the chain links, which I initially called “slave” chain. I wondered, what do the three-chain links mean? I know what the traditional slave chain quilts look like, having seen one at the Studio Museum years ago. Further study would reveal that the three chain links, a popular symbol of that era, were a reference to faith, hope and charity. Looking through the camera’s viewfinder, I focused the lens and shot the photo. I walked closer to see if there was anything else I wanted to shoot. My eye lingered on the symbol right next to the three links – I immediately saw what looked like an Adinkra symbol. I caught my breath. I went up for a closer look. My eye did an upward scan over the quilt and landed on what looked like the symbol for “Adinkrahene.” I eventually found at least three to four Adinkra symbols embedded within the symbolism of this quilt. I was in shock. How could these deeply African symbols end up in the “American Sampler” quilt?

I started naming the Adinkra symbols and their meaning aloud – the few folks around looked at me in amazement and called over one of the volunteers. No one knew what to do. I felt chills and something akin to genuine epiphany. Did an African woman make this quilt? Or did she participate in a quilting bee and blend her blocks in with the others? Did the other quilters know her meaning? The quilt is old and not in the best shape but is still notable for the variety of symbols and for the meticulous hand work. Did anyone else see what I saw?

I started naming the Adinkra symbols and their meaning aloud – the few folks around looked at me in amazement and called over one of the volunteers. No one knew what to do. I felt chills and something akin to genuine epiphany. Did an African woman make this quilt? Or did she participate in a quilting bee and blend her blocks in with the others? Did the other quilters know her meaning? The quilt is old and not in the best shape but is still notable for the variety of symbols and for the meticulous hand work. Did anyone else see what I saw?

I admired Infinite Variety for its historical breadth in the ingenious presentation of the quilts; however, I also found it frustrating. Most of the quilts were hung from the ceiling of the Park Avenue Armory, so it was impossible to see the backs of the quilts or get a real close-up view of them which might have revealed names, location and dates of completion. The show’s catalogue was published after the opening of the exhibition. I and many quilters felt that we were viewing the quilts out of context, as there was no signage accompanying the quilts to inform viewers of where the quilts were made, who made them, or where they were sold. To many of us who attended the exhibition, Infinite Variety raised more questions than it answered.

Over the next few months and years, the question “did I see what I think I saw,” has continued to haunt me. Sometimes one must act upon what is witnessed. I looked for the four symbols in the American visual lexicon and symbols found in quilts of that era. Could the red circle surrounded by two circles be a reference to sun and its rays? Or is it really Adinkrahene (meaning greatness) in a disguised form? There is “Nyamedua” (God’s Tree) in the Akan, could it be a reference to the tree of life or something else? The Star looks like a “star,” but it also closely resembles Nsoromma (meaning the son of God) in Akan. And so it is for the four-pronged leaf, Nserewa (meaning wealth/cowries), which looks like a flower. Duplicity and double meaning do a dance in this quilt.

I kept asking myself “why me?” “Why did I see the Adinkra?” The answers are many, but I will relay two examples from my past. In the 1980s, an Afro-Asian friend who had traveled to Ghana shared some of her books and experiences from her travels with me, and she allowed me to a copy a book on Adinkra symbols. I was even willing to carve them into gourds, though I had no clue where to find gourds back then. As soon as I saw those symbols — that hidden language — it spoke to me, and I knew I had to do something with them. It took a few years, but in 1983, I learned from artists Otto Neals and Emmett Wigglesworth at the Children’s Art Carnival in Harlem how to silkscreen on fabric and paper. It was supposed to be a workshop for children – but they had no takers, so they opened the workshop up to adults. How lucky for me and my sister, Gloria, who also took the workshop. The silkscreen workshop provided my first real opportunity to work with the Adinkra. I had a great time and even started a fledgling business “Free Spirit Connections Fabrics” – “for the culturally discriminating in taste.” I made no money, but it was a highly creative and fun time. Often, I would leave my job as a social worker, come home and set up my screens, silkscreen for a few hours, take them back down, and turn around and write for a few more hours. I learned these two art forms fed from the same source; yet each form fed the other and influenced the other. I still have the screens I made and the original acetate designs which I carved by hand.

During that same period, I signed up for a batik class at the Metropolitan Museum. The teacher was a Nigerian woman named Yemi, who was a student of the famed painter Twins Seven Seven. For some reason I could not take the class and sent my sister instead. She in turn taught me the batik process. Once again, I went back to the Adinkra symbols and chose “God’s Tree” and Gye Nyame, meaning “Only God,” to make my first batik cloth. I have lived with the Adinkra symbols a long time and would recognize many of them or combinations thereof.

The truth of that day is yes, the symbols did match between the photographs of the American Sampler quilt and book The Language of Adinkra Patterns, published by the University of Ghana in Legon. Yes, all four were either identical or very similar. Still, I was unsure if I should point this out.

What does it mean to claim some authority in a field that is riddled with the voice of the other? There a lean handful of African Americans providing scholarship, documentation, and writings on African American quilts. Notable among them are the late Cuesta Benberry, Al Freeman, Dr. Carolyn Mazloomi, and Kyra Hicks. Otherwise, the field is dominated by the gaze and opinion of men. Dr. Henry Drewal is the exception for a variety of reasons. Dr. Drewal curated the African Indian quilt show at the Schomburg a few years ago, and the show was done with integrity. The Gees Bend quilters and their relationship with their curator/discoverer was acted out in a more colonial model whereby ___ discovers them, buys their quilts for cheap; produces a book and national show which includes them, but they do not gain in the profits from the show. Several lawsuits later, the quilters are getting something back. All this is to say that curators and collectors vary in their impulse, sense of quilting, and ultimate relationship to both Indigenous, African American and diaspora quilting communities.

There is a need for Black women to speak about this craft and to open the dialogue in as many ways as possible. I want to suggest that there may be multiple sources for the variety of (medical, artistic, religious, civic and African) symbols found in the American Sampler quilt. Where are the black women discovering each other’s quilts? I am not yet a quilt historian. I am a quilter. I seek a broader answer to the question “did I see what I think I saw?” At best I hope to invite an alternative reading of the American Appliqué Sampler and yes, make peace with my quilting ancestors.