There are many ways of navigating through the desert. The Bedouin rely on mental images of a landscape that in the eyes of the uninitiated might seem devoid of landmarks, noting the exact shapes of the rocks, the curves of the wadis, the angles of the sun at different times of the day and year. Australian aborigines steer with memorized maps of ancestral songs and folktales that guide them back home, or even to places where they have never been. Our ease of navigation with the modern-day Global Positioning System threatens to deprive us of the more inner-oriented and mysterious dimensions of finding our way.

Navigation depends on situating yourself in the broader space around you, on aligning yourself with the landscape. To name, identify places, plants, rocks that are at first unfamiliar, to classify things encountered help you chart your way, as you incorporate these into your store of knowledge, into your language, your body’s spatial orientation.

Hiking down the dry bed of the Ovil stream that is filled with petrified testimonies of an ancient sea, Tamara is enraptured, steering from one fossil to another. Yael, coming across a rare plant, consults with our guide in a joint effort to identify it, then, like a foraging bee, aims for yet another flower further down the gorge. Eli finds his way through the desert with associations to Biblical quotations, or to beloved Hebrew songs. And I, I dance the Ovil’s twists and turns, inscribing this dry river’s flow in the arteries of my body.

Movement through rivers is not constant. Stone rivers pulsate, they expand, then narrow down, they fall precariously, and then saunter on. They run into other streams, a meeting takes place, a joining of forces. The ongoing flow pauses, there is a slowing down of pace, a punctuation mark in the sentence, a place to take another breath, to take account.

Soon the Ovil wadi broadens, and two other little streambeds run into it, creating a wide, open space – a crossing of rivers. Of course, running rivers never intersect – they join, become one. But when all three of these rivers are dry, a meeting takes place, forming a crossroads, a village square. It is a place that is geographically defined, that can be pinpointed on the map – a landmark.

On the bus, going past the sparse settlements on the road through the Arava Valley along the Jordanian border and contemplating the highly commercialized stops on the highway, I ask myself, what makes this a place? These locations were once classical desert oases, with tamarisks and date trees, distinguishing themselves from the “nowhere” of the desert. Here there is water, vegetation, and shade where otherwise there is none – a place to rest from the journey in the blistering sun. A place with distinctive features offered by the landscape, a place that can bear a name, that can gather significance, where things can happen. A place that can be remembered, for our culture lacks names for subtle textures, changes of light, fluctuations of space, and so the rest of the journey through the desert seems amorphous and undefined and easily slips into oblivion.

The Ovil streambed leaves the river junction, moving on between rocky walls that taper off as it runs into the broad, leisurely cruising bed of the Paran, with white, rounded river stones strewn in its flow. You can almost see the river of shiny pebbles sweeping across the desert towards the Arava, forming a wide plain of its own. Clearly, the Paran is the dominant stream, absorbing the floodwaters of the Ovil into its vast river basin. There is no crossroads here – it is not a fork of equals.

We start to walk upriver, towards the Sinai desert where this formidable river springs forth. Rivers are linear, they lead in their own direction – it is difficult to struggle against the stream in living waters. Yet, here in the arid bed of the Paran stream, which seems almost level, we walk upriver unhindered, contrary to its natural flow. The broad, empty, slow-moving riverbed has turned into a broad, global space that does not impose directions.

Pallid tamarisks grow here and there along the bed, and we find patches of a dusty green plant with bright yellow flowers in the middle of the pebbled flow. When you rub its fragrant leaves in the palms of your hand, they conjure up the sweet smell of apricots. I put some in my pocket to take home and make tea.

Sharp slanted layers of rock protrude out of the desert-sea like fins of sharks, evidence of geological upheavals millions of years ago. Our guide signals a turn to the left and the group starts to scramble up the steep mountainside. I look at the other hikers ahead, filing along the thin ridge, silhouetted against the morning sun, like the classic image of a camel caravan.

Soon I too reach that ridge, becoming one of the silhouetted figures myself, balancing apprehensively on the knife-edge path with terrifying drops on both sides. Below us, stuck on the mountain slope, an ominous black piece of cloth looks like a figure with a hat caught between the rocks in its fall and desiccated by the sun. A fate I would not want to share.

But the image of the caravan steadfastly moving along the thin edge remains before my eyes, providing me with a lifeline to hold onto that enables me to cast my fear of heights aside and walk freely, no longer sidetracked by the scary depths. As I reach the top of the path, I look back at the large, leaning rocks jutting out the earth’s surface that seemed so threatening before. There is something human about them in the soft winter light, as if they are tenderly supporting one another.

Soon after, we arrive at a flat overlook, where I finally feel completely safe. Here the immense spaces of the desert spread out around us in all directions. This, all this, is the biblical Wilderness of Paran, where the Israelites roamed for 40 years. Here my yearning for ‘elsewhere’ is awakened, my desire for wandering – both in the vast expanses of the world, and in the spaces inside myself.

So often, fears of the wide-open spaces are instilled in little girls to keep us close to home, teaching us not to take up space, not to spread ourselves out. In other words, to give up desire. For years, I struggled to overcome my own fears of untamed spaces, of the chaos beyond the secure cosmos, so that I could finally surrender to my own longing for the desert.

There is a dialectic between the desire to wander and the need to return home. Many wanderers reach a point when they have had enough of dispersion in the world and must settle down, to gather themselves, to be centered. To find a place of intimacy, of gestation.

We come upon such a center in the Sira stream, a small tributary that flows into the Paran riverbed a few kilometers west of where the road from the Ramon Crater to Eilat crosses over it. Walking up this little wadi we soon find ourselves in a small, semi-enclosed space, with a clearly defined entrance. As you cross that threshold, after a sharp bend in the narrow wadi, it opens up and you know, unquestionably, you have entered an extraordinary space – a space imbued with tranquility and silence. If the crossroads in the Ovil stream were a comma, then this valley in the Sira streambed is a full stop.

There is a cupping motion of the encircling hills, embracing you in their midst. These are not menacing cliffs, but gentle slopes on an amiable, human scale, defenseless hills with the texture of their under-skins exposed. A cream-colored mound rises in the middle of the space, with a skirt of soft folds flowing down its sides, the heart of a giant lotus.

Along the streambed, the valley floor is covered with a mass of bluish white limestone, where rhythmically undulating forms of gleaming rock lie lined up like reclining nudes bathing their backs in the sun. At times the figures seem wrapped in wrinkled cloth, revealing the muscles in their rounded bodies, at times disclosing the cords that fasten their garments. In the streambed, the white stone bodies become larger, more entangled, bent over, hugging one another, with dark hollows in between.

This precious little valley lies hidden, minutes away from the road, as cars go by and people rush towards their separate destinations, not suspecting its existence. Caravans, ages ago, traveled by in the broad Paran riverbed on their pilgrimage to holy places in the East, or in pursuit of the spice trade. This timeless little valley has always been there, shut off from the world.

There is a sense of awe when you chance upon a place that is so pure, when you see nature undisturbed, witness a sand dune that has no memory of human incursion, or glance at freshly fallen snow on which no living creature has tread. Places that transport you to the realm of the primordial, to the stillness of the world at the time of its creation, when no paths have yet been forged and all choices are still open.

After a long rest in the spell of the little valley, we prepare to continue our hike deeper into the dry riverbed, toward a waterfall formation that promises to be dramatic. Since it cannot be skirted, and we will have to return by the same route, my friend Nadira chooses to stay behind in the entrancing space. She has sensed its sacredness from the start, perhaps more clearly than any of us, and understands that she must give herself the time to draw in its otherworldly power – even if it means foregoing other sights that lie ahead. When we return, we find her sitting atop the valley’s central mound, a prairie dog sharpening her ears to the silence.

There are places that are numinous, where you can sense the dwelling of higher forces. Places of centering, anchoring you to the universe, places that awaken your inner peace, that nourish the spirit. Even though the desert in Jewish tradition is where the divine revelation took place, Judaism does not designate places in the desert as sacred. With a strong emphasis on social togetherness in modern Israel, the seeking of solitude was not particularly valued until very recently, while the language of conservation seldom refers to the sacred. “We do not know how to recognize sacredness,” laments Nadira, “Native Americans of the Southwest would surely have sanctified this place.”

As we take leave of the precious little valley in the afternoon light, the rounded stone figures have become the color of silver and the brown overcoat of the surrounding hills, in the reddish glow of the setting sun, has turned into a brilliant gold. It will remain hidden there, bearing no signs of our intrusion, like a body of water after the ripples have settled returns to its peaceful equilibrium.

***

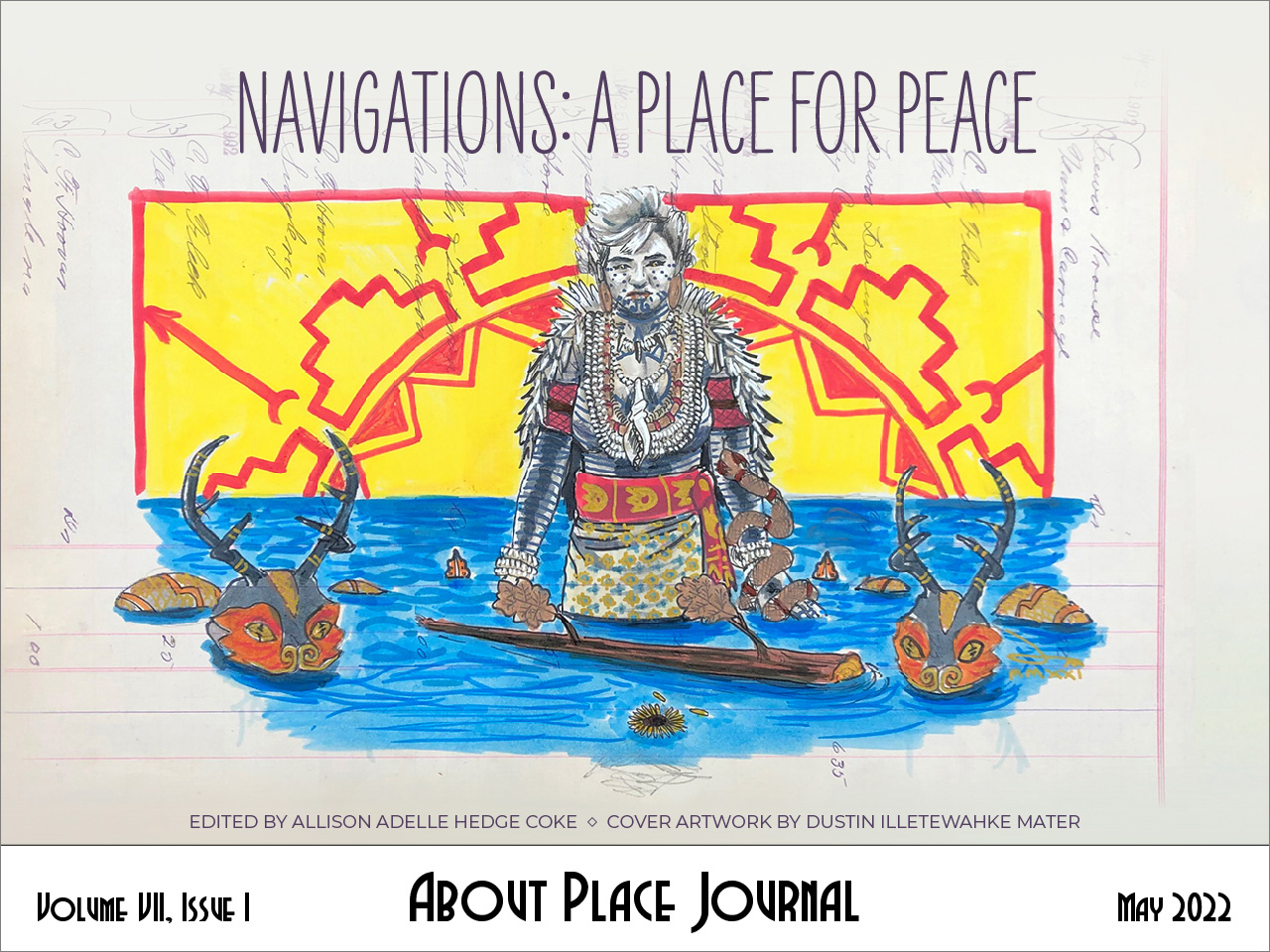

Photographs and text by Rita Mendes-Flohr

Note: I took the photographs included here on similar hikes in the Negev desert, and not necessarily on the hike described.