a literary journal published by the Black Earth Institute dedicated to re-forging the links between art and spirit, earth and society

DETROIT, PLACE AND SPACE TO BEGIN ANEW

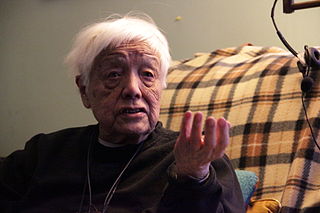

Photograph licensed to the Wikipedia Creative Commons with permission by Kyle McDonald

Excerpted from The Next American Revolution

by Grace Lee Boggs with Scott Kurashige

with permission by the University of California Press.

Detroit is a city of Hope rather the a city of Despair, The thousands of vacant lots and abandoned houses provide not only the space to begin anew but also the incentive to create innovative ways of making our living—ways that nurture our productive, cooperative, and caring selves….

As Detroiters we were very conscious of our city as a movement city. Out of the ashes of industrialization we decided to seize the opportunity to create a twenty-first century city, a city both rural and urban, which attracts people from all over the world because it understands the fundamental need of human beings at this stage of our evolution to relate more responsibly to one anther and to the Earth.

In pursuit of this vision we organized a Peoples Festival of community organizations in November 1991..to redefine and re-create a city of Community, Compassion, Cooperation, Participation and Enterprise in harmony with the Earth.1 A few months later, to engage young people in the movement to create this new kind of city, we founded Detroit Summer.. to rebuild, redefine, and respirit Detroit from the ground up.

Detroit Summer brought us into contact with the Gardening Angels, a loose network of mainly African-American southern-born elders, who planted gardens not only to produce healthier food for themselves but also to instill respect for Nature and process in young people. Getting starter kits of seeds and receiving tiller services from the city..these elders worked closely with youth from Detroit’s urban based 4-H programs, involving them in all aspects of gardening, nutrition and food preservation.

What has developed through both conscious organizing drives and the actions of many individual residents is a significant urban agricultural movement in Detroit. All over the city there are thousands of family gardens, more than two hundred community gardens, and dozens of school gardens. All over the city there are garden cluster centers that build relationships between gardeners living in the same area by organizing garden workdays and community meetings where participants share information on resources and how to preserve and market their produce. These clusters are providing a space of grassroots leaders to emerge.

This movement is very clear about the tangible benefits of urban agriculture: it provides fresh nutritious food, beautifies neighborhoods, creates neighborhood social capital, advances neighborhood economic development, stabilizes communities, and provides sustainability. But it also provides concrete examples of alternative, value-oriented means of securing our livelihoods. Detroit has arisen within the broader context of the emergence of national environmental justice movement.

The web of connections we have established through our community working in Detroit has continued to expand exponentially. A stream of visitors—ranging from youth to elders, veteran activists to those just getting involved, and celebrities to everyday people—have come to visit the city to witness the birth of a revolution and spread the message beyond Detroit. Among the hundreds of people to which the Boggs Center has given historical and political tours of the city are community activists of all races, prominent academics, elected officials, student groups studying urban issues or engaged in service-learning projects. At the same time Detroit Summer has hosted students from schools across the nation, such as Macalester College, the University of Minnesota, Oberlin, Antioch, UC Santa Cruz, Oakland University, Wayne State, and the University of Michigan.

Every August the Detroit Agricultural Network conducts a tour of community gardens. In 2007 six big buses were not enough for the hundreds of people of all ethnic groups attracted to Detroit’s mushrooming urban agricultural movement. After the tour, a retired city planner told me that it gave her a sense of how important community gardens are to a city. “They reduce neighborhood blight, build self-esteem among young people, provide them with structured activities from which they can see results, build leadership skills, provide healthy food, and a community base for economic development,” she commented. “I see it as the ‘Quiet Revolution.’ It is a revolution for self-determination taking place quietly in Detroit.”

This quiet revolution has been preparing Detroiters to meet today’s growing crisis of global warming and spiraling food prices. Instead of paying prices we can’t afford for produce grown on factory farms and imported from Florida and California in gas-guzzling, carbon monoxide-releasing trucks, we can grow our own food and not only achieve food security but grow our souls because we are creating a new balance between necessity and freedom. As Rebecca Solnit wrote in the July 2007 issue of Harper’s Magazine, “It is unfair, or at least deeply ironic, that black people in Detroit are being forced to undertake an experiment in utopian post-urbanism that appears to be uncomfortably similar to the sharecropping past their parents and grandparents sought to escape. There is no moral reason why they should do and be better that the rest of us—but there is a practical one. They have to.”2

While I believe that the urban agricultural movement carries a special significance in Detroit, I do not mean to suggest that such activities are only taking place here. Indeed, urban communities across the nation, faced with the consequences of deindustrialization, have gone back to the farm. One of the most inspiring examples I have witnessed is Growing Power, a two-acre urban farm on the northwest side of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where I attended a training session in March 2006. It was an unforgettable experience for me and the approximately seventy other participants, including youngsters and oldsters from all over the country and many different backgrounds. For example, I was in a project-planning workshop with Wesley, a thirteen-year old African-American middle schooler from the neighborhood, and Hank, a middle aged Puerto Rican psychiatrist interested in a similar urban farm in his Rochester, New York, neighborhood.

Growing Power is a fulfillment of the vision of six-foot, seven-inch tall Will Allen, the first African-American to play basketball for the University of Miami. Raised on a farm in Maryland, Will had treasured a sense of extended family and community that he experienced as a child because his family never lacked for food and took it for granted that they should share it with those in need. So, after a pro basketball career and working in sales and sales technology with Proctor and Gamble, he decided in the early 1990s to buy a two-acre plot in Greenhouse Alley, a small stretch of farms that fed Milwaukee in the early twentieth century,

Will began with a vision—a vision of Independence, independence from poverty, from chemicals, from far-off food sources, from farming techniques that are no longer viable given our ever-dwindling supply of farmland and fossil fuels, and also from the illusion that communities can exist without individuals accepting responsibility.

As a result, Growing Power has blossomed into a model food system that now includes year-round food production; sustainable energy and waste management; sales, marketing, and planning; and professional training, especially of urban youth and immigrants. Its Farm-City Market Basket Program provides a weekly basket of fresh produce grown by members of the Rainbow Farmer’s Cooperative to hundreds of low-income urban residents at a reduced cost. I was especially fascinated by the Youth Corps program, which starts kids out when they are eight or nine and works with them until they go to college. Kids get what the schools don’t provide. They work hard, learn how to think on their feet, and are challenged to solve problems instead of giving up and complaining when something doesn’t work out immediately.

Powerfully built and radiating energy, Will is directly involved in the local project, hosting thousands of visitors to Growing Power in Milwaukee each year while he mentors and works with groups all over the country, providing on-the-site training in how to build a sustainable food system. “We are not just growing food,” he declares. “We’re growing communities.”

When I think of this incredible movement that is already in motion, I feel a connection to the women in India who sparked the Chipko movement by hugging the trees to keep them from being cut down by private contractors. I also feel our kinship with the Zapatistas in Chiapas, who announced to the world on January 1, 1994, that their development was going to be grounded in their own culture and not stunted by NAFTA’s free market. And I think about how Detroiters can draw inspiration from these global struggles and how—just as in the ages of CIO unions and the Motown sound—our city can also serve as a beacon hope.

As I witness and participate in our visionary efforts to revitalize Detroit and contrast them with the multibillion dollars’ worth of megaprojects advanced by politicians and developers that involve casinos, giant stadiums, gentrification, and the Super Bowl, I am saddened by their shortsightedness. At the same time I rejoice in the energy being unleashed in the community by our human-scale programs that involve bringing the country back into the city and removing the walls between schools and communities, between generations, and between ethnic groups. And I am confident just as in the early twentieth century people came from around the world to marvel at the mass production lines pioneered by Henry Ford, in the twenty-first century they will also be coming to marvel at the thriving neighborhoods that are the fruit of our visionary programs.

My hope is that as more and different layers of the American people are subjected to economic and political strains and as recurrent disasters force us to recognize our role in begetting these disasters, a growing number of Americans will begin to recognize we are at one of those great turning points in history. Both for our livelihood and for our humanity we need to see progress not in terms of “having more” but in terms of growing our souls by creating community, mutual self-sufficiency, and cooperative relations with one another.

Living at the margins of the post industrialist capitalist order, we in Detroit are faced with a stark choice of how to develop ourselves to struggle. Should we squeeze out the last drop of life out of a failing, deteriorating, and unjust system? Or should we instead devote our creative and collective energies toward envisioning and building a radically different form of living?

Living at the margins of the post industrialist capitalist order, we in Detroit are faced with a stark choice of how to develop ourselves to struggle. Should we squeeze out the last drop of life out of a failing, deteriorating, and unjust system? Or should we instead devote our creative and collective energies toward envisioning and building a radically different form of living?

This is what revolutions are about. They are about creating a new society in the places and spaces left vacant by the disintegration of the old; about evolving to a higher Humanity, not higher buildings; about the Love of one another and of the Earth, not Hate; about Hope not Despair; about saying YES to Life and NO to War; about the change we want to see in the world.

1. Grace Lee Boggs, Living for Change, 231-32.

2. Solnit, “Detroit Arcadia,” 73.

Author Biographies

Grace Lee Boggs is an activist, writer, and speaker whose seven decades of political involvement encompass major U.S. social movements. Daughter of Chinese immigrants, Boggs received her Ph.D. in Philosophy from Bryn Mawr (1940). She developed a twenty-year political relationship with black Marxist, C.L.R. James, followed by Civil Rights and Black Power Movement activism in Detroit in partnership with husband and black autoworker, James Boggs (1919-93). Grace Lee Boggs’s published writings include Revolution and Evolution in the Twentieth Century (with James Boggs, Monthly Review Press, 1974; reissued with new introduction by Boggs, 2008); Conversations in Maine: Exploring Our Nation’s Future (with James Boggs, Freddy Paine, and Lyman Paine; South End Press, 1978). At age 95, Grace remains involved as a community activist. Her honors include honorary doctorates from 4 universities; lifetime achievement awards from the Detroit City Council, Organization of Chinese Americans, Anti-Defamation League (Michigan), Michigan Coalition for Human Rights, Museum of Chinese in the Americas, and Association for Asian American Studies; and a place in the National Women’s Hall of Fame and Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame.

©2026 Black Earth Institute. All rights reserved. | ISSN# 2327-784X | Site Admin